Naomi Rapeport is a retired specialist physician with an interest in South African Jewish Genealogy and Medical History. Colin Schamroth is a cardiologist in private practice in Johannesburg. Both have been extensively involved in the South African medical fraternity being past presidents of their respective societies and have both published widely in local and international medical journals.

.

Abstract: In 1918 an influenza pandemic known as ‘Spanish Flu’ swept the world. It had a devastating effect on the South African population. The duration of this pandemic was relatively brief, resulting in a high mortality in October and then abating significantly in the last two months of that year. There is scant information on how the pandemic affected the Jewish community of South Africa. Accessing data from Jewish burials and death certificates, we have identified over 300 Jewish persons who died of Spanish influenza in South Africa and analysed their demographic data. Fifty eight percent of the total deaths of Jewry for the year of 1918 took place during the period of the pandemic. Those identified were on average a decade younger than their non-influenza compatriots who died in the same year, and two-thirds were males. More South African Jews died in the pandemic than did South African Jewish soldiers during the First World War. The residual effects of the pandemic on the Jewish community were major and must have had a lasting effect.

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 killed an estimated 50 to 100 million people globally.1 It began early in the final year of World War I and claimed four to five times more lives than the war itself. German soldiers termed it ‘Blitzkatarrh’; British soldiers referred to it as ‘Flanders Grippe’; however, world-wide the pandemic came to be known as the “Spanish Flu”.2

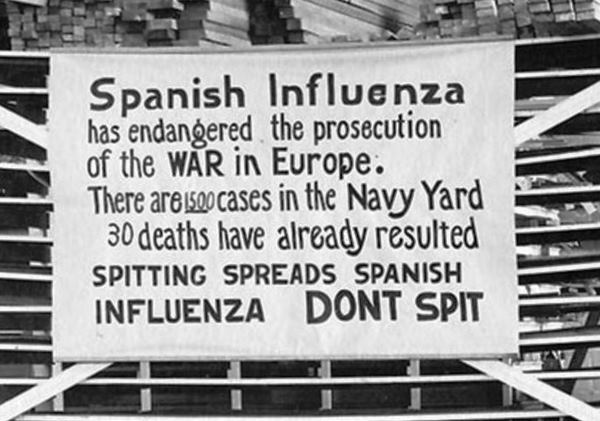

In Britain, under the Defence of the Realm Act, and the United States, the respective governments suppressed news of the outbreak. Public knowledge regarding the severity of the global health threat was hindered, as many news agencies were barred from writing about it, instead reporting solely on morale-boosting topics. However, as Spain was a neutral party in the war, newspapers were able to report on the effects that the illness was exhibiting in that country. Thus, it was generally perceived that this devastating illness originated in Spain, resulting in the pandemic being incorrectly labelled as “the Spanish Flu”.

Whereas previous pandemics had spread largely along trade routes, the war facilitated spread via the mass mobilisation of military personnel and civilians across the world.1 There were three waves of influenza. When the first wave began, in the early months of 1918 in the Northern Hemisphere, most doctors believed that they were dealing with an aggressive outbreak of common influenza. While illness rates were high during this initial wave, mortality rates were largely similar to the seasonal outbreaks of influenza.

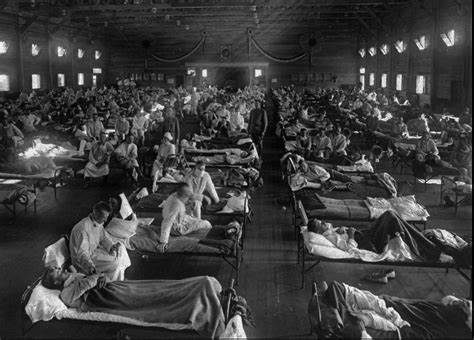

By the time of the Northern Hemisphere autumn of 1918, when the deadly second wave of influenza was hitting populations worldwide, the implications of the disease proved impossible to ignore. Whilst entire battalions were decimated, with both the Allied and the German forces suffering massive attrition, the details of many servicemen’s deaths were hidden to protect public morale. Meanwhile, the civilian population was being struck down in their homes.

Although the origins of the milder first wave continue to be debated, the origin of the lethal second wave is generally agreed to be the harbour town of Plymouth in Southern England. From this port, influenza easily spread to the rest of the world.3 On 25 July 1918, the Surgeon General Sir Humphry D Rolleston and Fleet Surgeon Robert WG Stewart arrived in Plymouth to investigate cases of serious illness arising from influenza. In August, the HMS Mantua, an armed merchant cruiser, set sail from Plymouth harbour for the British West African Colony (today Sierra Leone). On 8 August, an epidemic recorded as being due to influenza began on board. When the ship made port in Freetown on 14 August, there were 124 sick aboard. Once the influenza arrived at Freetown, it spread across the African continent. Ships that called in for coal at Freetown brought influenza to Cape Town, as well as to the Gold Coast (today Ghana). New Zealand soldiers who stopped in Freetown on their way to and from the war front in Europe facilitated the transfer of the virus to New Zealand.

A third and final wave of the pandemic appeared in many parts of the world in the early months of 1919. This wave generally overlapped the first wave in terms of geographical distribution; however, it seemed to spare areas where the second wave had been especially severe.

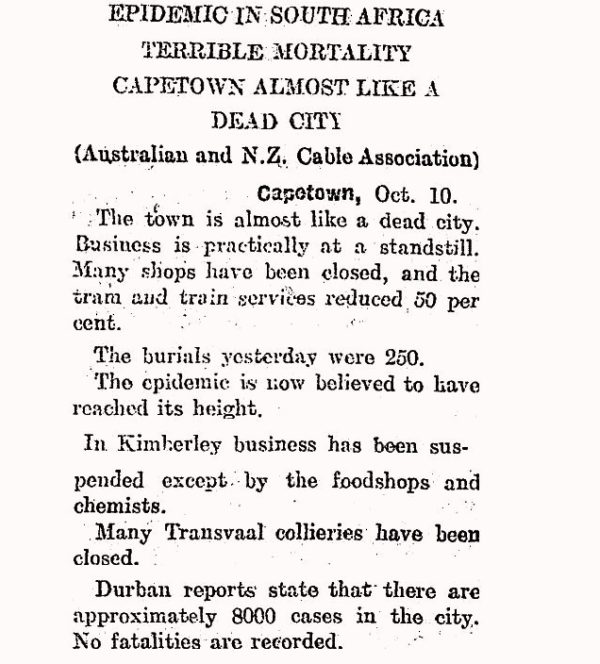

The first report of this influenza-like illness in South Africa was documented in Ladysmith, Natal Province in late August 1918.4 It affected people in the Natal interior, and followed the route of the railway lines, reaching the Witwatersrand region in the Transvaal Province by September 1918. This first wave of influenza had a relatively low mortality and it is postulated that this early exposure may have protected those infected from the more virulent second influenza wave. By the end of September 1918 the second virulent wave of the pandemic, brought over on two troop ships which had stopped in Freetown, struck South Africa.5,6 Although the troops were quarantined in Cape Town, those without symptoms were allowed to proceed home. They did so via the railways. Within a fortnight the country was overwhelmed by the worst natural disaster in its history. By the time it abated in early December, about 500 000 people had died. South Africa was the fifth hardest hit country worldwide.7 Locally, the disaster was subsequently known as ‘Black October’. The third, milder influenza wave occurred in August 1919 and largely spared the South African population.

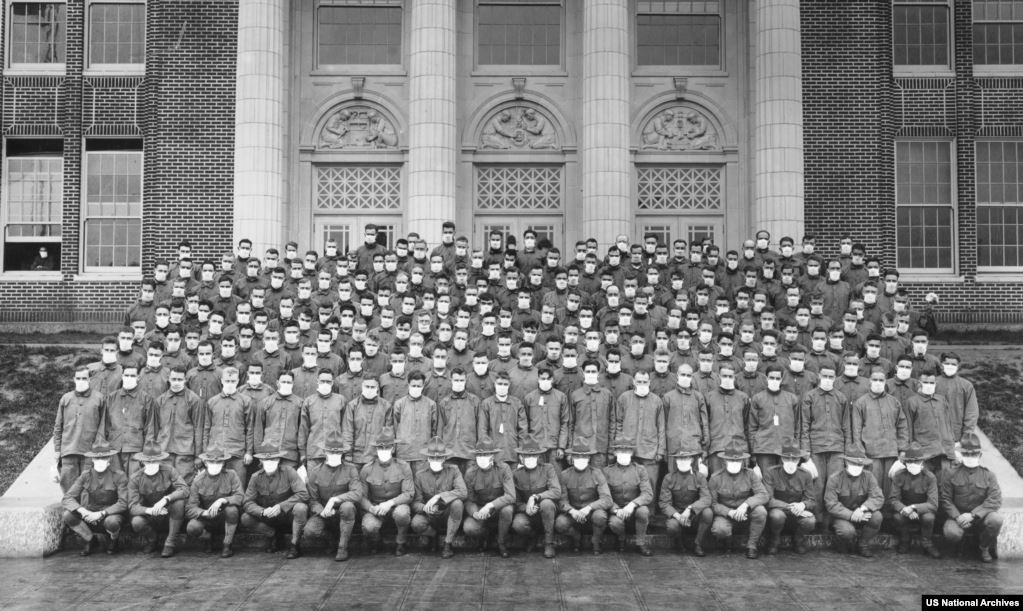

US Army Student Army Training corps members wearing "influenza masks", October 1918

Potentially, the most traumatic experience for South Africans during World War 1 was the enormous loss of life caused by the Spanish Flu and not the direct effects of the war itself.9 For nearly eighty years historians virtually ignored this subject.10 On perusal of local history textbooks, there is hardly a mention of the Spanish influenza pandemic and its effects on the population. Regarding the Jewish community, there are no known documents specifically dedicated to this. Only in the last three decades has there been an interest in the topic. The effects of Spanish influenza in the larger South Africa society has been extensively researched by Howard Phillips.8

Demographics of the South African Jewish Community in that period

There is very little information available regarding the Jewish community at the time of the pandemic. Published books deal predominantly with the period 1880-1910 and the period after 1920. They tend to skip World War 1 and the Spanish Influenza pandemic. However, they do contain some information regarding South African censuses.11.12

In the 1904 census of the four South African colonies, 38 096 Jews were recorded, comprising 3.4% of the white population. The four colonies were incorporated into the Union of South Africa in 1910 and thereafter designated as provinces. In the first census of the Union done on 7 May 1911, which represented the entire population of the country, the Jewish community was 46 926 persons, representing 3.7% of the white population. It had increased by 23.2% from the census of 1904. During this period, the proportion of women in the Jewish community increased from 32% to 41%. The greatest number of Jews were in the province of the Transvaal (25 892), followed by the Cape (16 744), Orange Free State (2808) and finally Natal (1482). A substantial number of Jews lived in smaller rural centres. This was reflected by the number of Jewish places of worship scattered throughout the country, 44 in total of which 21 were in the Cape, seventeen in the Transvaal, four in the Orange Free State and two in Natal.

As a result of the outbreak of World War I, the next census was rescheduled to 1918. It was confined to an enumeration of the white population only, which totalled 1 421 781.13 In this census of 5 May 1918, the Jewish community had grown to 58 741, an increase of 25.2% from 1911. The growth was largely due to immigration rather than the Jewish birth rate, which was noted to be lower than that of the general population. There was a steady influx of immigrants until the outbreak of the war. This slowed down substantially during the war years. 1804 Jews entered the country in 1913, 872 in 1914, 193 in 1915, 122 in 1916 and 41 in 1917. No official figures are available regarding immigration for the years 1918 to 1924.

Although a census was undertaken on 3 May 1921, no demographics of the Jewish community are available. The following census of 4 May 1926 showed a total Jewish population of 71 186, an increase of 21.2% from the 1918 census. There were 25 918 Jews in Johannesburg, 11 705 in Cape Town, 2277 in Pretoria, 1502 in Port Elizabeth, 1415 in Bloemfontein, 832 in Kimberley and 679 in East London.

During World War I approximately 3000 South African Jews participated in the war effort, representing about 6% of the Jewish community - a larger percentage than that of the general white population.11 679 Jewish soldiers are listed as having partaken in the war.14 The total number of recorded deaths amongst them was 144,15 including combat-related deaths, accident, malaria and at least eight deaths from Spanish influenza.

Source Documents and Methodology

The names of the deceased were sourced from the records of burials in South African Jewish cemeteries as registered on the website SA Jewish Rootsbank.14 All deaths recorded in the year 1918 were noted. They were then cross referenced with death certificates obtained from the website FamilySearch, whose images are courtesy of the National Archives of South Africa.16 Further data was gleaned from the websites of the Genealogical Society of South Africa, the SA War Graves Project and Geni, the genealogy and social networking website.15,17,18 Historical notes on the medical aspects of the influenza epidemic were obtained from the South African Medical Record, now called the South African Medical Journal. Historical notes of the Jews in South Africa were obtained predominantly from two local publications.19,20

For the months of October through to December 1918, deaths that were certified as influenza, with or without the diagnosis of pneumonia, or pneumonia alone were combined. The justification for this was based on documentation from 1918 that many of the deaths from influenza were recorded as pneumonia. The doctors of the time noted that patients’ symptoms could change rapidly “from a mild bronchial catarrh to a capillary bronchitis or a broncho or lobar pneumonia”.19 Other doctors reported “The prevalence of ‘pneumonia’ in South Africa during the past few weeks in which the influenza epidemic has raged throughout the land has been very marked, the appalling mortality being almost entirely due to ‘pneumonia’”.20 Subsequent literature has confirmed that the deaths were usually due to secondary bacterial infections, causing pneumonia.5 In the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) in the USA has taken a similar stance in its statistical analysis; “The CDC deaths due to COVID-19 may be misclassified as pneumonia deaths in the absence of positive test results, and pneumonia may appear on death certificates as a comorbid condition. Thus, increases in pneumonia deaths may be an indicator of excess COVID-19-related mortality”.21

In many instances, the date of death obtained from cemetery records differed from that noted on the death certificate. In most cases this was by a factor of one day and probably reflects the date of burial being confused with the date of death. Where possible the actual date of death was recorded. There were also some instances where the date of birth differed markedly; in those instances, the date written on the death certificate was taken to be the correct one.

In several cases the spelling of surnames differed. Some were Anglicized (e.g. Koren to Coren and Kantrowitz to Kentridge), whilst others had a similar Soundex (e.g. Silberstein and Silverstein, Nathanson and Nathenson), or had been abbreviated (e.g. Leyzerovitz to Lees and Katzin to Katz). In all instances, reconciliation was made using the information noted on the death certificate such as first and middle names, date of birth, country of origin, place of death and age at death, as well as information available from probates from the Master of the South African Supreme Court.

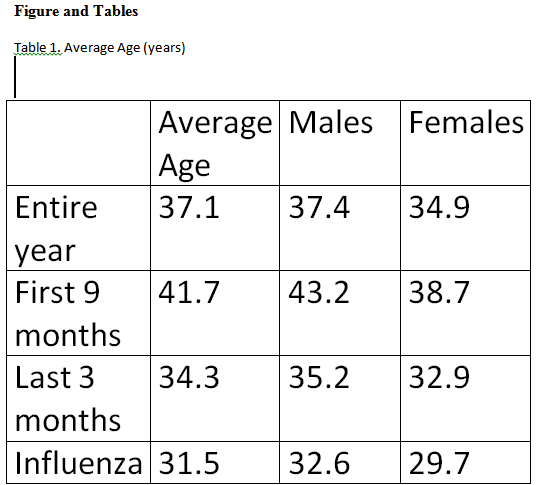

A total of 697 deaths were recorded for 1918 in seventy-two Jewish cemeteries in South Africa. There were 413 males, 244 females, 7 persons of unknown gender, and 33 stillbirths who did not have a gender available. The average age (excluding those below one year) was 37.1 years (males 37.4; females 34.9) with 15 persons of unknown age (Table 1). Of the 84 deaths listed in those below one year of age, forty were stillbirths. Three of the infants were recorded to have died of influenza of whom one was listed as being ‘influenza/premature’. In children aged between one and ten years, there were ten recorded influenza deaths.

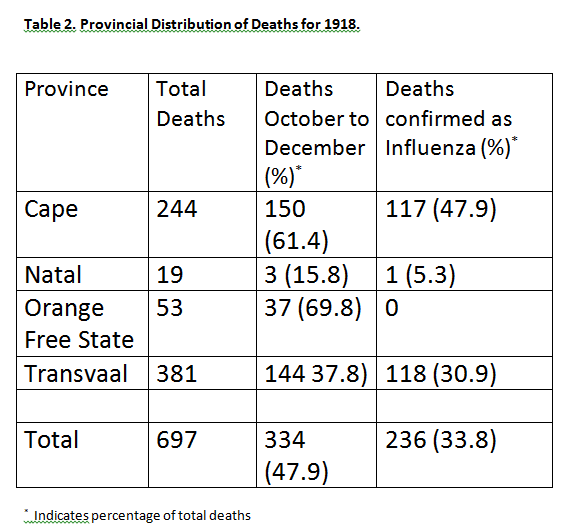

Within the cohort of 697 deaths, death certificates were available for 539 persons. Of the remaining 158 without a death certificates, most were buried in cemeteries in the Orange Free State. Of this cohort of 158 persons, 98 burials (62%) were recorded in the last three months of the year, when the second wave of the influenza pandemic was raging. Of the total deaths for the entire year of 1918, 58% took place in the last quarter, during the period of the pandemic. Combined certified influenza and pneumonia deaths for the year were 251. All the certified influenza deaths with or without a concomitant diagnosis of pneumonia (210) occurred in the year’s final quarter (October to December), and 26 of the 41 certified pneumonia deaths for the year occurred in that same period. Thus, the total used for the analysis of the certified influenza deaths was 236.

For the first nine months of 1918 the average age of death was 41.7 years (males 43.2; females 38.7, both excluding those below one year of age - Table 1). The average age for those in the last quarter was lower at 34.3 years (males 35.2; females 32.9). Within this group, those who died from influenza had an average age of 31.5 years (males 32.6 and females 29.7). In those who did not have a diagnosis, it was 35 years (males 35.4; females 34.4). Of the 62 deaths with a confirmed diagnosis other than influenza or pneumonia, six were infants below one year and the average age was 44.9 years (males 46.0; females 43.3).

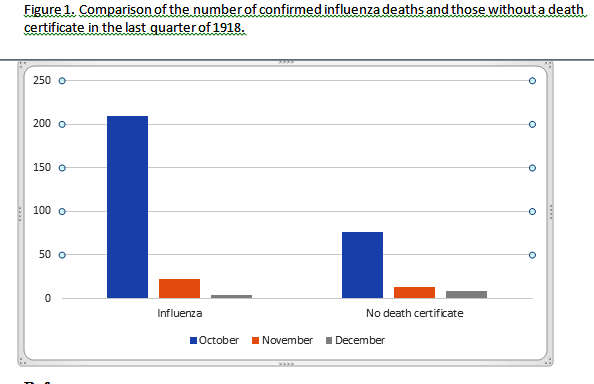

Of the 236 confirmed influenza deaths, 210 (89%) occurred in October, 22 in November and 4 in December (Figure 1). Of the 98 deaths without a death certificate, 76 (77.6%) occurred in October, 13 in November, and 9 in December. There were forty stillbirths in the 1918, of which 14 (35%) occurred in the last quarter of that year.

Of the 147 males with a confirmed diagnosis of influenza, 56 (38.4%) were married, 85 (57.8%) were single, four were children below the age of ten, and two adult males had unknown marital status. Of the 89 females, 68 (76.0%) were married, twelve (13.4%) were single and nine were children below the age of ten. All 68 married women who died of influenza were listed on their death certificates as being housewives. Among the twelve single women, three performed domestic duties, while the occupations of the rest ranged from a music teacher, to tailoress/milliner, a draper’s assistant, and a telephone operator. All the married men bar one had a career listed on their death certificate. These ranged from an advocate, to hawkers, general dealers, a cartographer, horse traders, farmers, engineers, and clerks, amongst a wide range of other occupations.

Other causes of death listed throughout the year of 1918 did not show any clustering except for nine cases of poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis). It is worth noting that the first ever documented epidemic of poliomyelitis in South Africa took place in early 1918, with eight of the nine poliomyelitis deaths recorded in these children occurring in the first three months of that year.22 Other medical conditions which are today uncommonly fatal included appendicitis (eight cases), diphtheria (two), dysentery/gastroenteritis (sixteen), scarlet fever (three), and typhoid fever (five).

Discussion

On review of the collated data regarding the South African Jewish community, in the last quarter of 1918 during the Spanish influenza pandemic, many similarities exist between the demographics of those persons with a known diagnosis of influenza and those who had no diagnosis. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the majority of the latter deaths were related to influenza. Thus, the true figure of influenza deaths in the South African Jewish community is probably well over 300 cases.

The demographics of our cohort also correlate with the demographics of pandemic in the white population of South Africa in that it affected younger people, mostly men, and was also associated with a higher incidence of stillbirths.8 The influenza deaths occurred in a young population, on average a decade younger than those who died from other causes in the first nine months (31.5 versus 41.7 years - Table 1). Many families were left without breadwinners and many children lost a parent. We recorded an instance of a husband and wife who resided in Carnarvon and died three days apart (12 and 15 October), leaving behind three minor children. The couple were buried in Britstown. A mother and son died within one day of each other in Cape Town (10 and 11 October); a brother and sister in Johannesburg died two weeks apart (14 and 30 October); two brothers in Kimberley died three weeks apart (7 and 31 October); two married sisters in Witbank died one day apart (17 and 18 October); a mother in Cape Town died one day (14 October) after giving birth to her third child and a mother in Johannesburg died following the birth of a stillborn child on 15 October. The effect of all this on the community must have been devastating.

Census data suggest that the Jewish population in South Africa experienced a reduced rate of growth following the pandemic. The population increase from 1904 to 1911 was 23.2%, from 1911 to 1918, 25.2% and from 1918 to 1926 21.2%. However, as the last census was eight years after the previous one and not at an interval of seven years like the others, the annualized increase in the Jewish population between these censuses was 3.3%, 3.6% and 2.6% respectively. Although World War I could well have had an influence on these figures, the effect of the influenza pandemic must have been much greater due to the greater number of lives lost.

In the Cape Province, the mortality was 61% indicating that it bore the brunt of the pandemic (150 of the 244 deaths for the entire year took place in the last quarter of the year; 117 with documented influenza and 33 with no diagnosis). When looking at the Transvaal, despite the postulate that the first wave of influenza, may have afforded a degree of protection against the second virulent wave of influenza, the mortality was 38% (144 of the 381 deaths for 1918 took place in the last quarter of the year; 118 with documented influenza and 26 with no diagnosis), indicating that the Transvaal was also severely affected (Table 2). As far as individual cities were concerned Cape Town, including the Cape peninsula, experienced a greater number of deaths (77 of 115 deaths for the year), versus Johannesburg (104 of 317).

On 24 November 1918, a memorial service for those who died in the pandemic was held at the Great Synagogue of Cape Town. There is a reference to 79 Jews in Cape Town who died.23 We have been able to identify 77 such persons. Among those listed were “nine Cohens and Mrs Annie Schus”.24 We have been able to find eight Cohens in the Cape Town and Muizenberg cemeteries. On the SA Jewish Rootsbank website only three Cohens are listed in the Cape Town cemetery records as having died in 1918 and two have their cause of death listed as ‘pneumonia’. One woman who died of influenza and is buried in Muizenburg, had the surname Wood, and her maiden name was Cohen. Five other Jewish Cohens were found on inspection of the Maitland Road Cemetery Record of Interments for the month of October and all had a death certificate diagnosis available. When inspecting death certificates of persons with the surname ‘Cohen’ from Cape Town, some were noted as persons of ‘coloured/mixed’ descent and therefore were unlikely to be Jewish and may have been buried in the non-Jewish cemeteries. This issue with the ‘Cohens’ highlights the problem of discrepancies between the archived cemetery records and sourced death certificates.

In Kimberley, Cape Province, twenty deaths are recorded in the last quarter of 1918, all occurring in the month of October. Of these, thirteen had documented influenza, six had no death certificate available, and there was one stillbirth. The deaths included two military men who were certified to have died from influenza. One, Lieutenant Herman Harry Feinhols, aged 36 years, was a company commander of the Cape Corp depot battalion in Kimberley, the same Corp whose soldiers returned home from the war in the two troopships that stopped in Freetown. He died on 8 October. The other was Corporal Louis Lipschitz of the South African Medical Corp who died a day later from influenza on 9 October, aged 22. His death certificate states that he was an electrician.

In Bloemfontein, Orange Free State, 18 deaths out of a total of 27 for the year occurred between October and December 1918. Unfortunately, there are no death certificates available for the individuals in this cemetery. Sixteen of the deaths occurred during the month of October; two of these persons did not have an age and one was an infant. Fifteen of these sixteen deaths occurred during the height of the influenza pandemic, and they were buried between the 13th and 26th October. It is stated that 64% of the total deaths in the white community of Bloemfontein during the influenza pandemic occurred in those aged 21 to 40 years. 8 Eleven of the 16 Jews (69%) buried that month were between the ages of 21 and 40 years, and their deaths are therefore most likely to have been due to influenza. These deaths occurred in a small community that in 1926 had only 1415 persons.

In several towns either all, or most of the burials for the year, took place in the last quarter of the year. These were mostly in the month of October, and the majority of these burials were related to influenza. In the Cape Province, in the towns of Britstown, Prieska and Queenstown all the burials for the entire year occurred during October. In Calvinia 3 out of 5 burials and in Robertson 2 out of 3 burials occurred during October. In East London 4 out of 5 burials occurred during October and November. In the Transvaal province, in Bethal and Standerton all the burials for the year were due to influenza. In both Krugersdorp and Pietersburg 2 out of 3 burials for the year were influenza related. In the towns of Potchefstroom, they were three out of five burials, Pretoria seven out of eleven and Witbank four out of five burials (including the two married sisters). In the Orange Free State, in the towns of Reitz and Vrede, all the burials were in October and early November. Harrismith recorded three out of five burials occurring in October, and in Kroonstad seven out of eight burials for the year took place in the last three months of the year. In Natal, influenza started in late August with the weaker strain. In Durban, there was only one burial in August and one in September in the Stellawood cemetery; neither were related to influenza. Four out of the thirteen burials for 2018 occurred between October and December and only one male had influenza listed on his death certificate. A 64-year old female did not have a death certificate and the other deaths were related to malaria and suicide. The only other town in the province to record a death during this time period was in Volksrust and this death was the only one for the whole year in that town. The finding of a low mortality due to influenza in Natal correlates with the postulate that the first wave of influenza may have afforded a degree of protection against the second more virulent wave in that province.

Phillips, in his thesis on the Spanish Influenza Epidemic, quotes from sources that there was a belief that amongst those who were afflicted by the Spanish Flu, “whites born in South Africa seemed to be more vulnerable than those who had grown up in Europe”.8 The Director of the South Africa Institute for Medical Research surmised that it was probable that most of the latter group may have developed a form of resistance or immunity due to exposure to other earlier epidemics in their home countries. Our data shows that only 65 of the 236 recorded influenza deaths occurred in persons born in Southern Africa, one of whom was born in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The majority of influenza deaths occurred in persons born overseas - 124 born in Eastern Europe, forty from the United Kingdom (33 from England), and seven from other countries. This finding therefore does not suggest that there was any form of immunity or resistance in the Jews who immigrated to South Africa.

Although we have only dealt with the deaths from influenza in the Jewish community, it is estimated that for every influenza death, ten to 35 were infected. 25,26 Obviously not all were symptomatic, but many must have been severely afflicted. The effects on the community were therefore far wider than the 300-plus individuals we estimate to have succumbed to influenza.

Notable Jews during the pandemic

In Kimberley, the town’s Board of Health appealed to the Public Health Department in Pretoria for medical assistance during the pandemic. The Union Defence Force's Acting Director of Medical Services, Colonel Alexander Jeremiah Orenstein (1887-1972) was despatched to Kimberley, arriving there on 13 October 1918. Within 24 hours of his arrival he remodelled the city’s campaign against the pandemic, converting it into a co-ordinated, well-directed system, the running of which was entrusted to the Board of Health. Three days later, he returned to Pretoria as the dire situation in the town was now under control. 27 Orenstein was the son of Russian Jewish immigrant parents and grew up in the United States of America. He came to Johannesburg, South Africa in 1914 where he worked for Rand Mines Ltd to reduce the high incidence of pneumonia and tuberculosis among gold miners. During both world wars, he was Director General of Medical Services in the South African Defence Force.

There is a record of the South African nurse, Dorah (Bunny) Bernstein (1888-1918) of Johannesburg, who served with the South African Military Nursing Services during the war. She died of Spanish Influenza whilst serving at the South African Military Hospital, Richmond, England on 6 November 1918.15

Three Jewish doctors died in the pandemic. Captain Dr Abraham Jassinowsky from Hopetown in the Cape Province was a member of the SA Medical Corp. He served in Windhoek, South West Africa (now Namibia) and died at the age of 29 years of influenza on 23 October 1918 in Windhoek. Dr Philip Roytowski, was a 33 year-old doctor in Potchefstroom who died on 28 October 1918.19 Dr Simon Alexander Kuny worked at the New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town, and died on 17 October 1918 at the age of 24. All three had trained overseas as the first South African Medical School (University of Cape Town) was only established in 1912, and its first graduates were capped in 1922.

Charles Friedlander, a barrister, co-founded the law firm Friedlander and Du Toit in Cape Town in 1899. The firm subsequently became C & A Friedlander Attorneys (incorporating his brothers, Arthur, Joseph, and Alfred) and it is still in existence. Charles was schooled in the Cape and furthered his education overseas at the universities of Berlin, Leyden, and Oxford. He died on 17 October at the age of 44.28

Jacob Mirvish, a poet and pharmacist, died of influenza in Cape Town. His father, Rabbi Moses Chaim Mirvish (1872 -1947), was rabbi of the Cape Town Orthodox Hebrew Congregation, and wrote two important books in Hebrew, the first of which was called Zichron Yakov (In memory of Jacob) published in 1924 and dedicated to his son.29

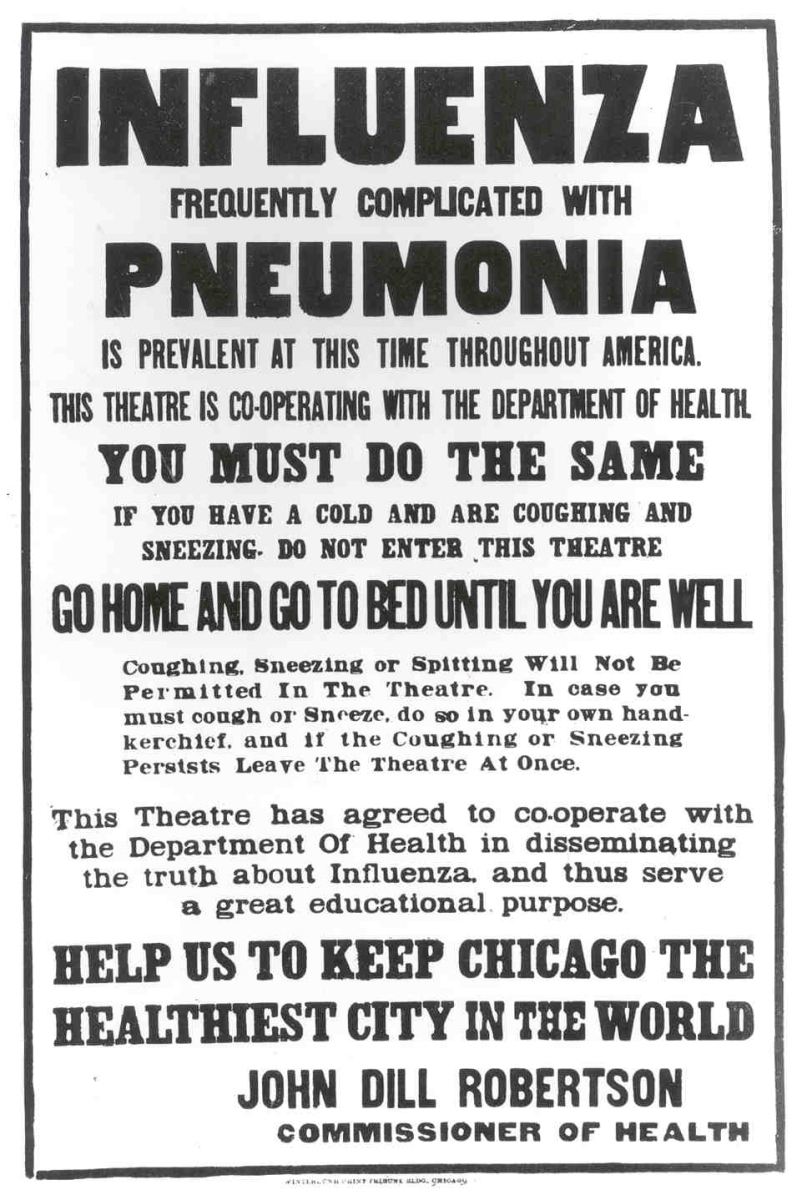

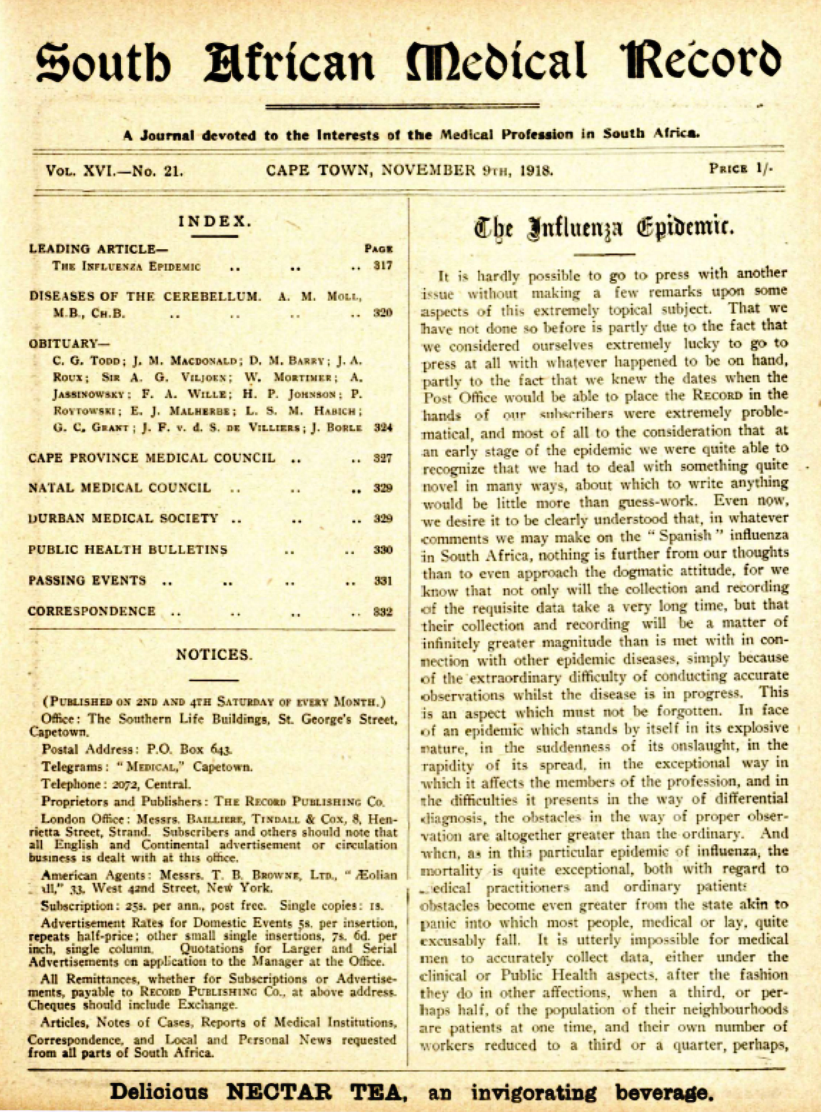

The leading article from the South African Medical Record of November 2018 regarding the Flu Epidemic

Conclusions

The Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918 inflicted a high toll on South African Jewry. This is confirmed by the number of deaths recorded during the virulent second wave of the pandemic, being just under half of that for the entire year. The demographics were similar to that noted in the general white population. In terms of the local Jewish community, considering the relatively young age of the cohort who died, many of whom were breadwinners and mothers with families, this pandemic must have left a devastating imprint. This study sheds some light on this epic tragedy.

Editor's Note:

Since the appearance of this article, JA has received the following response from Rachel Cook, editor Slateberry.com, which we are happy to share with our readers together with the link referred to:

I noticed you shared an article from CDC.gov when you talked about influenza pandemics, here: https://www.sajbd.org/index.ph...

We recently published an article that gives more context. Covid-19, which has caused more than 3 million deaths as of April 24, is a severe global problem. But in reality, it's “just” the fifth influenza pandemic since 1900. Here's the article: https://www.cusabio.com/c-21023.html

Here are a few questions we answer:

· How many deaths were recorded during the 1918 Spanish Flu?

· How did the Asian Flu in 1957 spread quickly to infect a quarter of a million people?

· What is the number of cases recorded in the first two weeks of the 1968 influenza pandemic?

· How was the 2009 H1N1 swine flu different from other seasonal influenza epidemics?

Finally, we share the history of Covid-19, its effect on our economy, and how we are fighting back.

References

- A year of terror and a century of reflection: perspectives on the great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. Nickol ME, Kindrachuk J. BMC Infect Dis. 2019 Feb 6;19(1):117.

- Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Medical History. Introduction: An Ill Wind. Arnold C. 2018. St. Martin's Publishing Group, New York.

- ‘Paths of Infection: The First World War and the Origins of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic’. Humphries MO. War in History 2014 Vol 21(1):55-81.

- ‘A Review of the Influenza Epidemic in Ladysmith and District’. Burman CEL. South African Medical Record. 1919 Jan 11;17(1):3-6.

- Reflections on the Spanish Flu pandemic after 80 years – causes, course, and consequences. History Department, University of Cape Town. 1998. Cape Town South Africa.

- In a Time of Plague: Memories of the ‘Spanish’ Flu Epidemic of 1918 in South Africa. Phillips H. 2018. Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town.

- The influenza epidemic. South Africa History Online. www.sahistory.org.za/article/i...

- Black October’: The Impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa. Howard Phillips. Thesis 1984. University of Cape Town.

- An Illustrated History of South Africa. General Editor Cameron T. Advisory Editor Spies SB. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg. 1986, p240

- Influenza Pandemic. Phillips H. International Encyclopaedia of the First World War 1914-1918 online. Version 1.0. October 2014.

- Saron, Gustav and Hotz, Louis (eds), The Jews in South Africa: A History. Oxford University Press, Cape Town. 1955

- The Jews in South Africa: An Illustrated history. Mendelsohn Richard and Shain Milton. 2008. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

- The Union of South Africa Censuses 1911-1960: An incomplete record. Christopher AJ. Historia 2011 November; 56(2):1-18.

- The South African Jewish Database Jewish Migration and Genealogy. www.jewishroots.uct.ac.za

- South Africa War Graves Project. www.southafricawargraves.org

- Genealogical Society of Utah. FamilySearch. www.familysearch.org.

- Genealogical Society of South Africa. www.eggsa.org.

- Geni.www.geni.com.

- Discussion on the Cape Town Influenza Epidemic. So Afr Med Record. 1918 Dec 14;16(23):353-359.

- The Pneumo-Catarrhal diathesis. Prevention and treatment of pneumonia and other respiratory infections by mixed vaccines. Major J Pratt Johnson. So Afr Med Record. 1918 Nov 23;16(22):335-344.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Vital Statistics System: Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) April 6th, 2020. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COV...

- Straws in the Wind: Early epidemics of poliomyelitis in Johannesburg 1918-1945. Wade MM. University of South Africa. December 2006.

- Black October: Cape Town and the Spanish Influenza of 1918. Howard Phillips. Studies in the History of Cape Town. 1979. Vol 1:88-106. Department of History, University of Cape Town.

- The Reb and the Rebel: Jewish narratives in South Africa 1892-1913. Ed Schrire C & Schrire G. Juta and Co (Pty) Ltd. August 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1948 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resou...

- Influenza, Historical: The Spanish Influenza of 1918-20. Mamelund SE. International Encyclopaedia of Public Health. 2008; p 597-609. Science Direct.

- S2A3 Bibliographical Database of Southern Africa Science. Orenstein, Dr Alexander Jeremiah (Public Health). 1879-1972.

- C & A Friedlander Attorneys. www.caf.co.za

- Biography: Rabbi Moses Chaim Mirvish (1872-1947). Helman C. JewishGen.org.