Douglas Davis, born in Pretoria, was exiled from South Africa in the mid-Sixties. He has since lived all over the world, including 10 years in Israel, where he was a senior editor of the Jerusalem Post. He was subsequently based in London as the paper’s European correspondent.

I didn’t know what to expect, but there was no doubt that the figure striding confidently into the car park of the Jerusalem Post was Denis Goldberg. He looked completely at ease; as though he belonged; as though he owned the place. He was slight, stocky and bald; a roly-poly figure with a bounce in his step. From a distance I could just detect a smile. He was still, as I remembered him: the cheeky-chappy.

‘Hey Denis,’ I called out as he approached, a rucksack slung over his right shoulder. He waved and headed towards me with renewed determination. How did twenty-two years in prison affect a man? I was almost afraid to look. But when he was close enough for me to make out his features, I had my answer.

‘My God, you’ve hardly changed at all.’

‘You must be…’ but before he could complete the sentence I gathered him up and we hugged each other.

‘Twenty-two bloody years. It’s been a long time.’

‘Do I know you?’ asked Denis. ‘Have we actually met?’

‘Not quite,’ I replied. ‘But the last time I saw you, you were in the dock at the Supreme Court in Pretoria.’

‘You were there? In court? Really?’ He was flushed with excitement.

His reaction to the news that I had witnessed the defining event in his life suggested that I was now here to acknowledge and validate the huge price he paid for his principles.

‘Yes, I was there. But I must tell you that after I heard the judge sentence you to four life terms I never expected to see you again.’

I looked again at Accused No. 3 (after Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu) whom I had last seen at the Rivonia Trial – the Trial of the Century in South Africa – and I was astonished that he had emerged, apparently undamaged, a free man.

Yet the question that filled my head at that moment had nothing to do with his heroics. How, I wondered, did this Jew – for he was unmistakably a Jew in appearance, intelligence, energy, warmth and ebullience – survive the darkest, most brutal days of the apartheid regime in a maximum security jail? Unlike the others who were convicted, all black, Denis was white and Jewish, a double traitor in the eyes of the regime. How had he survived? How did they let him survive?

But the questions could wait.

‘Is this all your luggage?’ I asked, levering the rucksack off Denis’s shoulder and heaving it into the boot of my snow-white Citroën. I unlocked the passenger door and ushered him in.

‘Let’s go.’

The image of Denis that had been in my mind since 1964 was of a rather vulnerable figure whose face was dominated by black, owlish glasses. He was almost swallowed up in the crush of his fellow-accused. The prisoners’ dock has been rebuilt and expanded but it was still inadequate for the ten most dangerous men to threaten the apartheid regime: Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Denis Goldberg…

After my initial shock at seeing the black and white accused together in a single dock – two other white accused, Lionel Bernstein and James Kantor, also Jews, were not convicted – it struck me that they all seemed to be so much older, larger, worldlier and better equipped for survival than Denis. They were grown-ups in a grown-up world, able to take care of themselves in the jungle of a tough prison system. Denis, then aged thirty, was the youngest of the accused. A boy among men.

The accused were intended to be humiliated and rendered anonymous in their identical, prison-issue khaki suits. But Mandela, even before he became Mandela, was a commanding figure. His natural authority was immediately evident, the obvious leader around whom the others fluttered during adjournments. Denis stood out, too, but for different reasons. He was a foot soldier: devoted, dedicated and no doubt technically savvy, but no leader. He was a natural corporal. He did not, never would, have the qualities of a general. He was destined to hang on the coat-tails of others.

His occasional caustic remarks in court revealed an acerbic, talented tongue. Such chutzpah, I thought then, might serve him well to keep up his courage and, perhaps, bring comfort to his fellow-accused, but I worried that it would become a liability when he entered the dark heart of the prison system. His jailers were unlikely to indulge his barmitzvah-boy cleverness for long. Still, that was the most optimistic scenario: the smart money was on death sentences.

Denis, a civil engineer, was rounded up with virtually the entire high command of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress, when police raided their headquarters on 11 July 1963 (Mandela himself had been scooped up in a road block and was already in prison). The headquarters, a secluded, sprawling complex known as Liliesleaf Farm, was situated in a discreet outer suburb of Johannesburg, Rivonia.

Anne-Marie Wolpe, Judge Albie Sachs, Denis Goldberg and SA Jewish Board of Deputies President Zev Krengel. The picture was taken at a panel discussion on Jewish responses to apartheid held at Liliesleaf heritage centre, July 2013.

Like most of the others, Denis was charged with fomenting revolution, recruiting others to train in the use of explosives, conspiring to assist foreign troops when they invaded South Africa, and soliciting funds from sympathisers abroad. Each charge carried a death sentence. All of the accused were probably saved from the hangman’s noose by Mandela’s carefully calculated final statement from the dock, which amounted to a challenge to the judge: a non-racial, democratic South Africa was an ideal which he hoped to live to see, but one for which he was, if necessary, prepared to die. Denis was found guilty and sentenced to four life terms.

He had reason to expect the worst. According to one report, the military shopping list he oversaw called for 48 000 land mines each containing five pounds of dynamite, 210 000 hand-grenades, each containing a quarter of a pound of dynamite, as well as petrol bombs, syringe bombs, thermite bombs, 1500 timing devices for bombs and Molotov cocktails. The requirements also included 144 tons of ammonium nitrate, 21.6 tons of aluminium powder and 15 tons of black powder. There were provisions for a nucleus army of 7000 soldiers, many to be trained abroad. The combat doctrine was based on the successful Algerian and Cuban models.

In 1985, twenty-two years after the Rivonia arrests, Denis was made an offer he couldn’t refuse: freedom in exchange for his signature on a document in which he renounced the use of violence. The deal was brokered with the South African regime by a remarkable Israeli. Herut Lapid, a kibbutznik, had set himself the daunting task of freeing Jews from prisons around the world – wherever they were, whatever their offences. Well almost. He won the freedom of murderers and bank robbers, but he declined to campaign for anyone whose conviction involved drugs. Denis’s case fell well within his remit and Lapid plunged in enthusiastically. A similar deal had been rejected by Mandela; Denis accepted it. He was soon on a plane bound for Tel Aviv – and freedom.

A few days after Denis arrived in Israel, I tracked him down to Kibbutz Ma’ayan Baruch, the home of his daughter, a couple of miles from the border with Lebanon.

‘Can we get together for an interview?’

I was surprised by his immediate and enthusiastic response: ‘I’ll come to Jerusalem tomorrow.’ Then, after a moment’s pause, he asked shyly: ‘Could you put me up for a few days.’

That is how the chief bomb-maker of Umkhonto we Sizwe came to be sitting in my car, on his way to meet my family, to live indefinitely as a guest in my home.

We drove through Jerusalem on a perfect afternoon in early spring. The Old City walls glowed gold in the light of the setting sun and Denis was staring intently at the chaotic traffic and busy people around us. His face was pressed to the car window like a child outside a toyshop on Christmas Eve, greedily sucking up the sights and sounds. His reaction was not, I suspected, because he was at the epicentre of the Jewish world but because he has not seen so much activity for twenty-two years.

‘You can’t imagine how exciting this is for me,’ he said with childish relish. ‘So many cars, so many people, so many colours, so much movement, so much excitement… It gives me a real high.’

Then came the highlight of his journey: ‘Hey, look at that,’ he cried out. ‘I can’t believe it… Did you see? There’s a guy carrying an entire fridge on his back with just one strap around him holding it on.’ He turned and watched the labourer’s progress until he was out of sight.

‘I hope I’m not being a nuisance,’ said Denis, as we left the commercial centre of the city and headed into the suburbs.

‘Of course not. But I warn you that the accommodation is fairly spartan. Two rather small storage rooms, knocked together, adjoining our apartment.’

‘That sounds great.’

‘Be careful what you wish for,’ I said. ‘There is a bed, a cupboard and only one small, square external window. And I’m afraid to tell you that we call it ‘The Cell’.

‘Perfect,’ said Denis. ‘If there’s one thing I know about, it’s cells.’

Denis was free, but he was a man in torment. And he was eager to talk about it almost as soon as he deposited his rucksack, still unpacked, on to his bed in ‘The Cell’. Should he have agreed to the terms of the South African authorities in exchange for his freedom? What role would he be play in the future of the ANC? Would he have any role in the future? And how would his comrades react to news that he had struck a deal? Would they ever trust him again? Would they forgive him and accept him back into the inner circle? Or would his moment of weakness, his eagerness for freedom, expunge the merits of his twenty-two-year sacrifice and cast him into political oblivion?

I feared that the answers would not bring him the comfort he sought. Liberation movements do not deal kindly with those who are perceived to break the bonds of solidarity and strike bargains with the enemy, even in moments of weakness. Especially in moments of weakness.

‘We’ll speak later,’ I assured him, ‘when we’ve had dinner and the children are in bed.’

His face brightened at the mention of children.

‘Can I meet them now?’

Denis was enchanted. His focus switched entirely to the children, aged four to eleven. The torment of freedom was banished and, once again, he was totally absorbed and at ease. He sat and entertained them while they had their evening meal, coaxing out every detail about each one of them: what they were learning in school, their favourite games, their best friends. Then, always asking permission first, he read them bedtime stories and, when the moment came, he tucked each of the four into bed and, reluctantly, switched off their lights.

He rose each morning at five, still in synch with the prison regime, and was showered and dressed before any of the family was up. When the children awoke, he sat with them at the kitchen table, transfixed, as he watched them eat their cornflake breakfast. And the children responded to the love and warmth he showed them. They were accustomed to guests who came for dinner and stayed for days or weeks or months. It had happened more than once. But they were not accustomed to such high-octane adoration.

‘You don’t have to do that,’ I said after he waved them goodbye on his first morning with us.

‘It’s a great pleasure,’ he replied. ‘I love children, and… well, it’s been twenty-two years since I’ve seen and held a child. You cannot imagine how much this means to me.’

I was beginning to detect several discrete personalities encased in this highly compartmentalised body. Denis not only loved children but somehow seemed to be one of them. Did his emergence as a bomb-maker, I wonder, coincide with the birth of his own children? Was his decision to embrace public violence perhaps a desperate cry for attention at a time when his own small children were soaking up all the emotional and physical energy at home? What was clear was that several personalities were coexisting within a single, spare frame: the man who adored children, the adult who struggled to be one of them, and the cold-eyed saboteur who was ready to kill for his cause. Charming Denis meet Ruthless Goldberg.

All this touched on other questions that intruded unbidden into my mind: why, after a separation of two decades, did he so enthusiastically accept my invitation and volunteer to come to Jerusalem – unless he was desperate to get away from the working ideal of the collective kibbutz? Or desperate to get away from his daughter? And why did he not mention his son, who was in London? Or his wife, also in London?

The answer to the last question came almost immediately. Would I mind, he asked, if he called his wife from our phone the following morning? He had not spoken to her since his arrival in Israel. I guessed that he had not spoken to her for over two decades, since she last visited him in prison.

It was clear that Denis was estranged from his family. His wife, faced with arbitrary arrest and constant police harassment, moved to London with their two children, aged nine and eleven, just two years after Denis was sentenced. There, she constructed a new life for herself. I suspected, too, that Denis was estranged from his children. Sadly, his Marxist ideological commitment prevented him from taking pride in their life choices and achievements: his daughter had become a Zionist and was living a happy and contented life on a kibbutz (the most positive example of the Marxist ideal), while his son was a successful stockbroker in London. They might have been justified in harbouring a sense of grievance that their father’s political commitments had deprived them of a normal childhood.

But I believed Denis’s alienation from his family was secondary to his concern about the effect on his reputation of his decision to snatch at freedom while his ANC colleagues continued to languish in jail.

When Denis turned off the children’s lights, he found me in the lounge and sat down in a chair opposite.

‘Can we have that talk – remember, you promised?’

And so we began hours of discussion which continued long into that night and the subsequent nights he spent with us.

I asked him the first question that occurred to me when we met in the car park that afternoon: how did he survive all those years in jail?

‘When I finished school I trained as a civil engineer. In prison I held on to my sanity by returning to studies through the University of South Africa [a distance-learning institution which offers degrees by correspondence]. I now have degrees in public administration, history, geography, and library science. The downside of my release was that I was still halfway through a law degree…’

He was on a roll. The words tumbled out and his face shone with a boyish exuberance. Denis was clearly an intelligent man. That was the first point – the most important impression – he wanted to make.

But for all that, he continued, his ability to endure prison life was becoming increasingly hard to bear. ‘For the past six months I felt I had had enough. I felt it was time to go.’

And so, when he received the offer of freedom, his psychological need to get out was at its height. ‘At that stage, I just couldn’t carry on.’ He paused. ‘I have always had a conflict between my duty to the movement and my own personal needs.’ And that is as close as he ever came to any meaningful introspection or analysis of his predicament.

‘What now?’ I asked. ‘What does the future hold for you?’

He talked immediately of his passions – his love of art, theatre and music, particularly opera. He cannot wait to attend his first post-prison performance.

Then, suddenly, without warning, his mood changed and he returned to the issues he had raised in ‘The Cell’. For the first time, his tone bordered on self-pity. It was the dominant theme in our conversations from then on. Had he betrayed his comrades? Had he tarnished his reputation forever by accepting the conditions set by his jailers for his release? Had he, after all those years in jail, squandered the opportunity of a place in the pantheon of South African resistance leaders? Had he betrayed his pristine Marxist credentials?

He was consumed with the urgent need to do penance for having acted venally by accepting the Israeli-inspired solution; to expiate the mortal sin he felt he now carried. He concluded that he would find salvation only by devoting the rest of his life to working for the African National Congress in London – working in any capacity, however menial, ‘even if that means turning the handle on a Gestetner machine putting out ANC literature’.

‘You know, Denis, I remember your reaction when you were sentenced to life.’

‘You do?’

‘Yes, when the judge sentenced you to life, you called out, “Life! Life is wonderful!” Don’t you think there’s a clue to your future in what you yourself said then?’

‘Meaning?’

‘Meaning you’ve done what you’ve done, you’ve paid the price – a huge price – and now you have earned the right to a normal life. Give yourself a break. Take walks in the park. Enjoy the theatre, visit art galleries, go to the opera, listen to music. Get to know your family again. Start living. You don’t have to walk around like the man with the fridge on his back. Life is wonderful.’

He looked at me for a moment, and I sensed his excitement at the prospect of what freedom offered. But I knew that he also sensed the danger. His identity was totally bound up with his ideological convictions. I was challenging not only his political commitment but also the core of his identity. He realised it, too, as he leant forward, his head resting in his hands, rocking slowly from side to side.

‘How can I do that? How can I? I understand what you’re saying, but it would mean all those years in jail were meaningless. All the sacrifice for nothing. I can’t do it. I just can’t.’

‘You’re in a psychological clip-joint, Denis. For God’s sake, get out now. You’ve already paid a high price. It’s time to go before the price goes up again. This is your chance to escape from the past.’

‘No, no, no…’

‘You have a very rare gift,’ I tell him.

He looks at me, almost imploring: ‘What’s that?’

‘You have a gift for life – you have the passion, the energy and the capacity to extract every ounce of pleasure out of life. There are clearly things that you love, that give you great enjoyment. You have a family. You have your freedom back. There are decades to catch up on. Carpe Diem. This is your opportunity. Seize the moment.’

I felt I had his attention again. He was silent for a moment. Then he shook his head again. Slowly, sadly. I detected a momentary flicker, but no, he could not let go of the need to give meaning to the sacrifice he has made.

‘If I do that,’ he said, ‘it will mean that my years in jail were meaningless. A complete waste. I can’t just walk away from everything I have done.’

In spite of his incarceration, Denis retained an enormous vibrancy. Despite his protests, I sensed his pent-up need to take huge gulps of freedom, his appetite to taste life again. I told him that, having sacrificed so much for the fight against apartheid, it was time to put down the burden and devote the rest of his life to family, friends and activities that gave him genuine pleasure. He could, of course, choose the self-flagellating ‘Gestetner’ route, but he really needed to find an occupation that offered a greater challenge to his intelligence than the handle of a duplicating machine. And, having already sacrificed so much that gives meaning to ordinary people’s lives, he still had the opportunity to make up for lost time and enjoy the pleasures, great and small, of a normal life. Who would blame him?

We were locked in a circular argument. From time to time, he seemed to light up at the possibilities, but just as quickly the light was extinguished by the central contradiction in his life: Denis was a natural bon vivant, but he was also a doctrinaire Marxist. He seemed to feel guilty about pleasure. In a perverse sense, I think he actually derived pleasure from pain, which was now entirely self-administered: the more he suffered, the closer he would come to absolution; to expiating the sin of his final collaboration. He could not acknowledge that those twenty-two years in jail were simply wasted, or at least that it was time to move on. They must be made to mean something, however discredited he might have become in the eyes of his comrades for having succumbed to a faustian pact with the apartheid authorities.

I realised then that I was not about to change the course of Denis’s life. He did not contemplate settling in Israel, which he found to be an ideological embarrassment, and I had no desire to convert him to Zionism. But he was still in his fifties and had a life ahead of him. I implored him to consider his next steps with the greatest care.

The following night we repeated the conversation. This time I had a task for him. It is the Jewish festival of Purim and next morning the children would go to school in the fancy-dress costumes that my wife, Helen, had made for the occasion. The big girl would be a queen, the younger a witch, and the big boy would be a pirate.

‘As the chief military officer of Umkhonto we Sizwe,’ I asked, ‘would you make a weapon for my little pirate?’

‘It will be a great pleasure,’ he said. Another night of conversation ended at daybreak, by which time Denis had produced an elaborate and wonderfully decorated cardboard dagger which would be the envy of every child in my son’s class.

But amid the fun, Denis was also morose. He had had the first of what would be several very long conversations with his wife in London. From the little he told me, I presumed that they were discussing the possibility of getting together again, and I presumed that she did not regard the prospect of a reconciliation with unmitigated enthusiasm. I had probed deeply into his life, but I did not inquire into this most sensitive issue, and he did not offer any explanation. What I did understand was that putting the pieces of a marriage together after a twenty-year hiatus was a complicated business.

Then, after the fifth morning of whispered conversations, a deal was apparently struck and Denis ended the conversation with a huge beam. He would, he announced, be leaving for London the following day. But on the evening before he left, we receive sad news about a child in our neighbourhood, a contemporary of our son. While walking to the local shopping centre on an errand that afternoon, the boy had idly kicked at a plastic pipe on the footpath. It was a bomb and the boy’s foot was amputated in the explosion. We were distraught at the news. Denis was in tears.

There were more tears the following morning when Denis hugged and kissed each of the children as they left for school. A couple of hours later, his rucksack back on his shoulder, he embraced Helen and I warmly before setting off in a taxi on the first leg of his journey to London that evening. My last image was of Denis blowing us kisses as his taxi disappeared.

We never saw or heard from Dennis again. Not directly. There was no letter of appreciation for our hospitality. Nor was there any acknowledgement of the succour he received from Israel or the role that one dedicated Israeli had played in securing his freedom.

But we did receive an indirect message from him. Somehow, between leaving our home and boarding his flight to London, Denis managed to give an interview to a Hebrew-language newspaper in which he is reported to have justified indiscriminate acts of terrorism by Palestinians on Israelis, even if those attacks led to the mutilation and death of innocent children. And in the many long and self-serving interviews he has given since leaving our home, he never fails to attack Israel and Israelis. In case he has erased his encounter with Israel from his memory, I hope this helps him to adjust his personal biography.

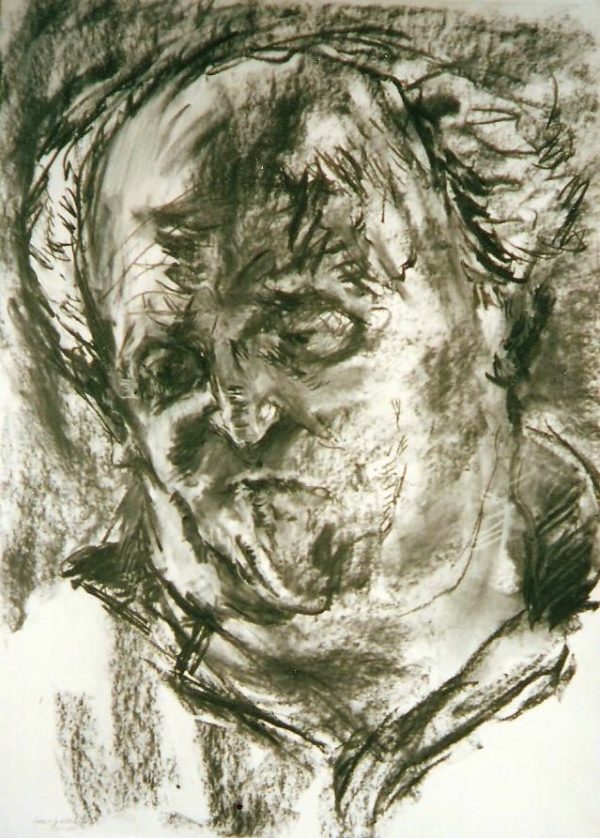

Portrait of Denis Goldberg by fellow former prisoner Paul Trewhela, London, 2002

I am a simple journalist, lacking the skills of the psychologist. But it is necessary, even for a simple hack, to observe human behaviour, to try to get under the skin of interview subjects in order to understand what makes them tick; what makes them behave as they do.

At the time of his arrest, Denis was thirty years old. I can understand young, unencumbered men taking fantastic risks to promote profoundly held beliefs, but the husband of a young wife and two small children? How could he have risked all that? If he had calculated the risk, as he would have done, he must have known he would almost certainly be captured. And it was highly likely that he would face the death penalty; at the very least, life in prison. By taking the decision he did, he was effectively abandoning his family.

Was this the behaviour of a man who loved children? Or was this the behaviour of a man with the impulses and instincts of a child; a man who was, perhaps, unable to cope with the attention lavished on his own children and desperate to reclaim the limelight for himself? He expressed unlimited love and commitment for the ANC and Marxism, yet showed no remorse for having spent the best part of his marriage and virtually all of his children’s childhood in a distant prison cell.

I did not ask why he left his daughter and her kibbutz after just a few days to move in with us. I guessed she might have been less understanding of the uncertainties and ambiguities that he carried to Israel in that meagre rucksack. Nor did I ask about his wife and his son in London, and he did not mention them. Of course, I judge him, but I can afford to judge with a degree of impassivity. I do so without the pain of an abandoned wife or children, who must have suffered terribly from his absence.

I believe that, for Denis, the unkindest cut of all is that he was plucked from the darkness of his prison cell and carried to the bright light of freedom by a man who was a proud Jew and Israeli. And the reason that the kibbutznik Herut Lapid had moved heaven and earth to secure his release was precisely because Denis himself was a Jew. Nor was Denis in any doubt about this.

‘He assured me it was not a political issue,’ he says. ‘He told me he was doing it because I was Jewish – a “member of the family”,’ adding ungraciously: ‘I’ve never heard such nonsense.’

Perhaps not. But was this the same Denis who, on a matter of principle, was prepared to turn his back on his family and spend the best years of their life in jail? Where was the principle that failed to compel him to reject the outstretched hand of the Jew who fought for his freedom? Why did he not simply explain that he did not consider himself a Jew and that his saviour was labouring under a misapprehension; that he did not believe the Jews were a family, a tribe or a people, who, like others, harboured legitimate national aspirations; that he simply could not accept the offer if it was being made on such a basis? Where were his principles when Herut Lapid offered him the chance of freedom – as a Jew?

Most prisoners, like Denis, who can expect their release to come only with the angel of death, might regard a rescuer as an angel of mercy. But for Denis, Herut Lapid was no more than an agent of Zionist imperialism, a legitimate target for Palestinians terrorism – as, of course, was I and my family.

I understand much of the process. I came from a similar genetic pool and had travelled a similar path. Like Denis, I had been spat out by the country of my birth, disconnected myself from my people and regarded the Jewish national home as a colonial aberration. Unlike Denis, I had the great good fortune to find my way back, reconciling body and soul, restoring my identity and my place in the world, while regaining a sense of equilibrium in my life. And all that without resiling from my opposition to apartheid or compromising my loathing of racism.

I had offered Denis the chance to change the trajectory of his story, to regain his authentic identity, to reassess his future. Ultimately, though, he found it easier to cling to his grab-bag of clapped-out ideological orthodoxies.

Which leaves one final question. Could he really have started a new life without the detritus of the old or was he too afraid of the person he might have met across the ideological divide? Charting a new path, however uncertain, would have involved a potentially perilous journey into unknown territory. It might have been exhilarating, it might have been dangerous, but ultimately he did not have the stomach for the challenge. I know he was tempted, but he could not, would not, take the leap. Instead, he chose to remain locked in the sterility of an ideological prison which he had crafted and from which there was no escape. It was, in my view, a cowardly decision. And a treacherous one.

Treachery is a big word, but it is hard to find a more accurate description. Denis betrayed the trust not only of his family, faith, history, culture and heritage, but also of Israel, the country that had granted him refuge, and the people who had offered him sanctuary. Behind the warm, ebullient exterior beat an icy heart. He was an alienated, eviscerated soul who was incapable of abandoning the dream of his Marxist idyll and of living with a more realistic sense of who and what he is.

Denis Goldberg did pay the price for cutting a deal with the apartheid regime. He would perform menial service for the ANC in London for a further seventeen years before returning to South Africa. And when he did, all that time he had spent in jail – and all that time he had labored for the ANC – did not translate into so much as a hero’s welcome. Unlike two fellow Jewish Marxists, Joe Slovo and Ronnie Kasrils, both of whom had spent the apartheid years in exile, there was no high-profile political job for the hapless, deracinated Denis. Instead, he was thrown a bone and appointed a special adviser to Kasrils, who was then Minister of Water Affairs and Forestry.

Denis Goldberg, a confusing mass of duplicity and self-delusion, could not escape his past. He had become its victim.

READERS' COMMENTS

While I respect Douglas Davis's writing on contemporary anti-Semitism, I think my portrait of Denis Goldberg speaks against the tone of Davis's article in the current issue of Jewish Affairs. Had he spent time in prison in South Africa with Denis Goldberg in the struggle against apartheid, he would not have written the way he did.

I first met Denis 58 years ago in Cape Town, and was with him again in prison in Pretoria three years later. He was an inspirational person to be with, and he kept us prisoners in good spirits.

As the only white person to face the death sentence with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and their colleagues when convicted in June 1964 before being sentenced to life imprisonment the next day, Denis was possibly the most central person to validate the ANC's non-racial perspective. The Pan Africanist Congress - and especially its military wing, Poqo, which had already killed white construction workers at Bashee Bridge in Eastern Cape in February 1963 - was dynamic and increasingly popular in opposition to the ANC when Denis and his colleagues were arrested in Rivonia in July 1963.

"It's life, and life is wonderful!" - his shout to his mother after being sentenced (she hadn't heard properly) - has remained his belief, right to this year when, suffering from terminal cancer, in his wheelchair, he said: "“We were in crisis then, and we are in crisis now. And only the people can get it right."

The deaths of his first wife, Esme (whom he rejoined in London after 23 years in prison), of his second wife, Edelgard (who died in South Africa), and of his daughter, Hilary, were borne with the same courage.

My portrait was made in London in 2002 before Denis returned to South Africa with Edelgard. A second portrait is at Liliesleaf Museum in Rivonia. A third is in his Heart of Hope collection at Hout Bay.

Denis deserves respect, and gratitude.

Paul Trewhela

Aylesbury, UK.