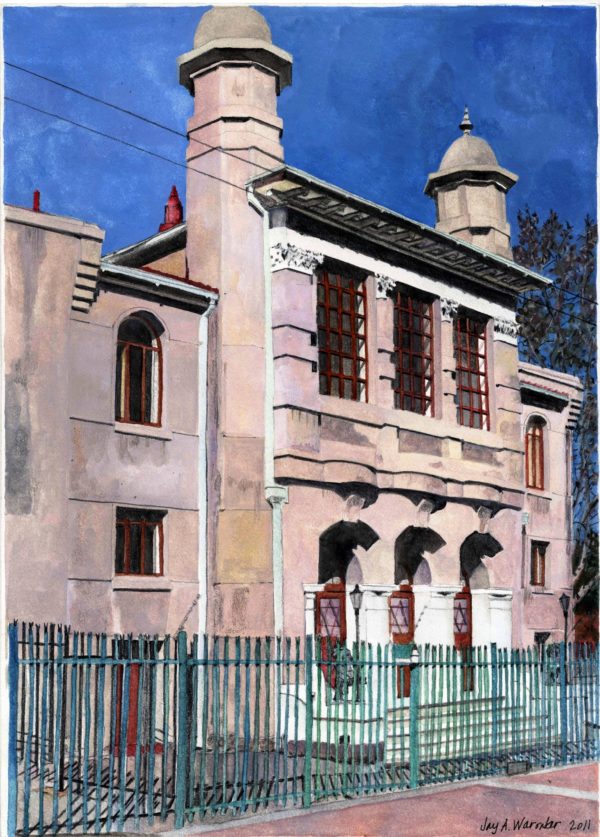

Zita Nurok, a regular contributor to Jewish Affairs, is an elementary school teacher who grew up in South Africa. She is a member of the National League of American Pen Women, and has served as Vice-President and President of the Indianapolis branch. The two watercolours, painted by architectural historian and artist Jay Waronker in 2012, show the exterior and interior of the Doornfontein Hebrew Congregation (aka 'the 'Lions Shul'). The editor thanks Mr Waronker for his permission to reproduce them.

Doornfontein – the suburb of meaningful beginnings that grew into big happenings in the bustling city of Johannesburg. Businesses both Jewish and non-Jewish were established in this suburb, especially along the main thoroughfare of Beit Street where each contribution was sewn into the fabric of the growing city, creating a colourful quilt that enriched the society…….butcheries, bakeries, tailor-shops, groceries, dairies, liquor stores, shoe-maker shops, barbers, and more.

The deli is the place where Jewish people meet not only to shop on a Friday for Shabbos, but also to slip comfortably into their home-tongues of Yiddish that they refuse to relinquish even years after immigrating to South Africa in search of a ‘bigger’ life. They came off the boats to seek their fortunes in the city of gold – Johannesburg. Behind the counters plump Jewish mamas relate stories to each other in heavy accents as they wait for customers. They exchange gossip of the week past.

‘Yes dahling, what can I do for you?’ one of the mamas asks a customer who is deciding what to buy. She enumerates a long list of tempting foods too great to resist, as the customer makes her decisions. Cold cuts for the family who come for lunch on Sundays, coleslaw, beetroot salad, lokshen kugel… the herring counter offers salt herrings, chopped herring prepared mama’s way, sweet Danish herring, and cream herring all in large covered bowls.

A blue box marked JNF with a map of Israel engraved on it, waits on the counter. Customers put small change into the slot until it is finally filled, even before the end of the day.

An African child stands on shoeless tiptoes as he stretches over the counter. ‘Give me some bread.’ he begs. He’s dressed in shredded khaki shorts and an oversized colorful, checked shirt. His cracked and dry little hands reach out as the kindly assistant gives him two day - old buns. He runs out to sit with his friends on the sidewalk in the sun.

‘Who’s next please? Yes dahling, can I get you something?’ Her voice rises above the bustle of the deli, and out onto the sunlit street through the open door. ‘Hamantaschen for Purim, perogen for soup, gefilte fish for Shabbos, brown or white taiglach to have with lemon tea….’

New limousines parked outside the deli are noticeable against the backdrop of old shops and washing hanging out of the windows of flatlets above.

The fruit and vegetable shop further on has its own enticing atmosphere. Colors of fresh fruit and vegetables packed in thin tomato-box trays dazzle the eyes as customers walk in, some with their grass-woven shopping baskets. The choices of fruits are overwhelming, and sweet smells penetrate the senses, filling customers with a yen to reach out, to touch and taste each piece of produce.

The market gardener is usually Portuguese. A heavy odour of cooked garlic pervades the area in which he moves. His nails and hands are stained from handling fresh sandy potatoes, pulling off the tops of beetroot and carrots, or from wrapping his sales in newspaper. His worn shoes are a muddy brown.

‘Yes missus, can I halp you?’ he asks a bejewelled lady perusing the produce. His accent too is heavy. In the early days of his business he realized that people bargain with him, so he ups his prices, waiting for a counteroffer. His black hair hangs on an over-worked brow as he looks at his customers with dark eyes. He repeats the same well-versed words to each customer: ‘I give it to you cost price. You buy two, I give you cheap.’ He confidently wraps the choice he has made for her. ‘You want mangoes?’ he points to the ageing yellow fruit. There are two types: the kidney-shaped, or the round, fleshy, juicy ones. When the lady agrees he throws in an extra one as a gesture of smart salesmanship.

‘Manuel,’ he yells in the direction of the backyard. ‘Come and halp with the box.’ A wiry teenager springs from the back of the shop. He picks up the now filled box and follows the woman carrying her basket to her shining new car. The veins on his arms bulge with weight as he places it into the boot of the car. He waits for a tip, then dodges vehicles on the busy road, and returns to his job.

Adding to the hum of Beit Street, small groups of pot-bellied Jewish men gather on street corners smoking pipes, reminiscing about ‘der haym’ in Europe where the tomatoes were redder, the potatoes fatter, the bread fresher, the goats gave sweeter milk, and the cheese richer. They look forward to meeting again at shul on a Friday night or Saturday morning.

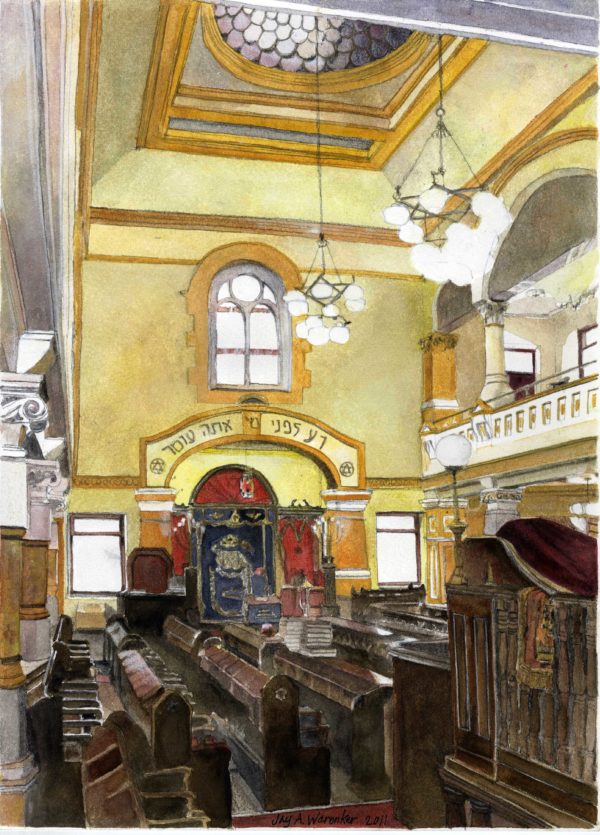

The Lions Shul on Beit Street was built back in 1906. It has been said that the two lions that adorn the front, refer to the tribe of Judah, one of the twelve tribes described in the Torah. The walls of this shul hold stories of those Jewish immigrants from Europe who arrived in Doornfontein, started over, and built new lives for themselves and for their families. Religious books brought from Eastern Europe years ago, give special meaning to the prayers, songs, and words that continue to remind loyal congregants of their connections to life in this old suburb as they return from other parts of the city, often on Shabbat and on High Holidays.

Interior of the Doornfontein Hebrew Congregation synagogue (Jay Waronker, 2012)

Asher’s Kosher Butchery, just one of the butcheries on Beit Street, invites shoppers to come in. The butcher is indeed a meaty looking individual with excess fat hanging over the belt of his wide-legged grey pants. His overpowering voice can be heard down the road before people even get to the squeaky wood-framed swing door. The roar of his voice above the sounds of the machines that saw the carcasses instils dread in his workers. A carpet of sawdust covers the cold cement floor. It absorbs any remaining dripping blood from animals fresh from the abattoir, slung over the plastic mackintoshes of workers who deliver prey to the butcher. Sheep, lamb, and cow are heaved into a cold soulless walk-in ice chest at the back of the butchery. The sawdust is swept up each evening, then a fresh layer is poured onto the floor.

Beit Street continues to be an exploration of lands and cultures.

Next door to Asher’s is Nicky’s café. The handsome Greek and his wife Tina, own it. During the week their two children Georgina and Christophoulos run home from the local school close by to help their parents. As decreed by the Board of Health when customers buy bread, they must wrap the loaves of sandwich bread, home-made brown, or rye bread in rectangular tissue paper which lies in a pile beside the cash register. During an infrequent lull they unpack boxes, rearrange stocks, and read comics. Cigarettes, candy bars, gum, boxes of chocolates, matches, biscuits, and canned goods, overload the shelves behind the till. Newspapers are stacked in piles where people enter. The Rand Daily Mail sells out as it comes in. The Evening Star too sells out almost as it’s put down on the cement floor. Large pickles, green and black olives fill trays in a closed counter. When its doors are opened for sales, rich smells of feta cheese escape into the store.

Nicky’s outgoing manner encourages female customers to flirt with him. He teases and laughs, enjoying the flattery. His wife laughs with him as she busies herself. She is beautiful enough to contend with her husband’s habits. Greek friends lounge on counters, heavy in conversation, oblivious of the traffic in the shop. Sounds from two pin-ball machines at the back of the cafe compete with the ringing of the cash register. The popping of bottles being opened on the opener which hides inside the cold-drink refrigerator doorframe, are like steady rain drops on a corrugated iron roof. Greek music playing on the radio, muffles the noise of passing traffic. African workers from a building site down the road invade the café at lunch times. They each purchase half a loaf of bread, and a small carton of milk which they devour out in the sun, sitting on the curb in front of the café. On Saturday mornings children from the surrounding neighborhood constantly stream in and out for ice-cream, suckers, bubble gum, lucky packets, and sweets which Nicky slaps across the counter at a remarkable rate.

Doornfontein Hebrew Congregation (Jay Waronker, 2012)

But as the years passed increasing changes heralded a different world, and a different multi-cultural South Africa. 1982 saw hypermarkets opening throughout the city. Shoppers adapted to busy parking lots, shopping carts to fill as they entered the store, aisles stocked with varieties of the same items, causing a different type of dilemma for those deciding what to buy, numerous check-out counters, workers in uniforms. This concept of ‘bigger’ foretold the world that was to come: busy freeways, challenging traffic, numerous high-rise buildings, crowded and sparkling shopping malls, all with relevant job opportunities fueled by the advances of technology. This was to become the new way of life.

And so, the businesses and special places on Beit Street are left to nestle cosily in our memories of ‘life as it used to be’ back then.

We are left to wonder “Is bigger better, or was smaller richer?”