Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. Having trained as an economic historian, she now researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters and has a regular book review column on the online Heritage Portal. She is Vice-chairperson of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and a voluntary docent at the Wits Arts Museum. This article has been adapted from her original tribute that appeared on the Heritage Portal in February 2020 and appears with the kind permission of same.

.

Art publishing impresario and photographer Helen Aron, who passed away in Johannesburg on 11 January 2020, was a unique Johannesburg character. A documentary and art photographer of Johannesburg’s disappearing past and a woman of passion, intelligence, flair and great courage, she will be well remembered by the Heritage community.

Helen Aron was born on 30 November 1939 to German Jewish immigrant parents Arthur and Sofie Aron. There is an entry for her father in South African Jewry, 1965 (p201). He is described as a “Business Proprietor” and their family address given as Orapa Mansions, Yeo Street, Yeoville. So Helen was a daughter of Yeoville when it was very much a Jewish suburb with its synagogues and Jewish bakeries and grocery stores along Raleigh and Rockey Streets. She was unusual in that unlike most other Jewish people, she continued to live in this node of Johannesburg – Yeoville, Berea, Hillbrow and Bellevue.

Helen matriculated in 1957 at Barnato Park, or as it was more formally known, Johannesburg Girls High School in Berea. For a century, this was the Girls’ high school (of course, only for white girls). It was a fine institution, modelled on the belief that girls too should be educated in literature, languages, sciences and mathematics, and also be sports women. It welcomed immigrant children and moulded them into liberal English speaking South Africans, with questioning minds. There were many fine career teachers at the school.

Helen Aron and Noel Hutton (town planner), photo by Marion Laserson

Helen did not go on to university and always said she regretted not having a higher education. Nevertheless, she was an avid reader, particularly of newspapers. Mary Boyease remembers being told by her that she had worked in Public Relations at Anglo American on that remarkable in-house journal OPTIMA. That perhaps explains her early photographic work. Fellow heritage champion Marian Laserson relates that one of Helen’s early jobs was photographing the horse race finishes (those photo finish shots) – requiring lightening reflexes and rushing to her studio to develop and print if there was a dispute as to who won. She adds that she never learned to us a digital camera, believing in an older technology, when photography really did require an artistic eye and careful attention to shutter speeds and light.

Helen was also an active and keen member of the Institute of Innovators and Inventors. According to Laserson, she invented a complicated storage system of boxes about the size of large shoe boxes which could clip together and would be strong enough to form a partition in a room.

A Johannesburg person through and through, Helen enjoyed living in ‘old’ Johannesburg – she stayed put when others migrated or emigrated in the face of a demographic and political revolution. At the time of her passing she lived in a lovely small apartment block in Sharp Street, Bellevue, called Panoramic View. It was a block that was probably erected in the fifties or sixties, when Bellevue was a popular and pleasant place to live and be a city girl. Arthur Aron was a property owner and she inherited a couple of buildings from him. There was thus that side of Helen that practically applied herself to repairs, renewals, tenant problems and partnership with “bakkie builders”. She always cared about people and had no side or snobbishness.

At the peak of her career, Helen was a champion of Parktown (or Park Town as she always called it). She undertook the massive project of the special commemorative boxed portfolio Park Town 1892 – 1972, with 51 of her photographic images of disappearing Parktown together with commissioning the significant book on Parktown with the essays by Clive Chipkin, Arnold Benjamin and Shirley Zar.

Benjamin wrote on the social history of Parktown, Chipkin about the baronial architecture of the suburb and the use of prefabricated iron and Zar on Parktown as the garden suburb and its town planning. The campaign to save Parktown was solidly underpinned by these serious, significant research studies. Helen was the one who coordinated the publication, which absorbed her time energy and investment for many months, and she is acknowledged for her conception and realization. The Portfolio was beautifully printed in limited edition in Switzerland on thick cream card/paper.

As Parktown began to change and disappear so did this portfolio raise the flag and awaken the city fathers and citizens to the history of Johannesburg and the importance of conserving what remained in that suburb. After all, in 1972 Johannesburg was just 86 years old - a young city with no respect for its important buildings. Joburg’s habit was to invest, speculate, build, use, demolish and rebuild new and bigger buildings. Helen was one of a small group from the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust who fought the loss of Parktown, as office blocks appeared and developers offered home owners tantalizing prices.

The expansion into Parktown of higher educational institutions, such as Wits, was both a negative and a positive. The coherent pattern of residential clusters gave way to large scale campus development and residences, though some prime heritage houses such as Outeniqua and North Lodge were saved. The old Transvaal Provincial Administration was the biggest destroyer of all with their triumphal positioning of the then new all white Johannesburg Hospital (now the Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital) and the Wits Medical School on the Parktown Ridge. By the time the Parktown portfolio had appeared, the M1 motorway had sliced through estates, houses and gardens, pulverising the Witwatersrand Parktown Ridge. It was all ‘progress’ and it all but obliterated the old expansive, grand Parktown, whose history dated back to the 1890s. The Aron portfolio served as a record of its social history and was an epitaph of note. It was also an expression of Helen’s defiant activism in the face of the bulldozers and insensitive new town planners.

The portfolio of her photographs and the Parktown book rapidly became collectable. Comments Marion Laserson, “What was unusual was that Helen financed the publication herself, through her photographic company, Studio 35 publications and was much admired for both the photographs and for her energetic entrepreneurial enterprise. She was doing self- publishing well before the internet age made it all so much easier. I am still of the opinion that the series of essays commissioned by her hold their own and remain pioneering benchmarks. The portfolio was a work of art”.

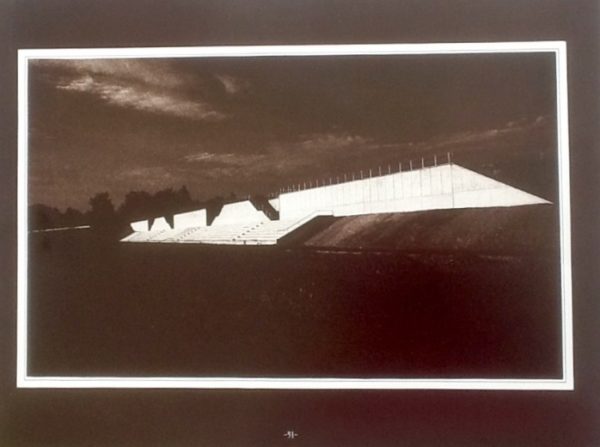

Helen’s photo of the new College of Education Campus on the Parktown site - old Parktown demolished to make way for a sports stadium and new brutalist architecture of the academic buildings.

Clive Chipkin remembers: “Anyone who knew Helen Aron encountered a formidable, talented, eccentric, engaging personality. We met in 1970 when she came charging into the Parktown office where I was working and said without introduction, “I’ve found you – we have got to work together on Parktown before its gone”. This was the beginning of that marvellous book Parktown 1892-1972, with its evocative sepia photographs. It was the beginning too of a six month period of chaotic interruptions with her maniac drive to get the book done against the odds. Those atmospheric sepia photos, which she took, caught the neurotic quality in late Victorian era continuing into the early years of the 20th Century”.

Shirley Zar remembers Helen as a talented, perceptive photographer: “Helen broke new ground before everyone else talked heritage and conservation. She recognized why Parktown‘s disappearance should be recorded. Helen made a masterpiece of her production of the Parktown portfolio. She wanted an artefact – a work of art.”

Flo Bird writes: “Helen served on the board of the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust for many years. Her enthusiasm stemmed from the work she had done photographing the houses which were mostly demolished for the development of the Johannesburg College of Education. But she also protested vehemently against noise and graffiti. Helen became a keen environmentalist as well as a heritage conservationist”.

Alkis Doucakis remembers: “One just cannot forget Helen Aron! We met only a few times -- the first was in the late 1990s, the last about five years ago -- yet it was she who always saw me first and, with a loud, "Hello Alkis", and a big smile would rush to give me a big, sincere warm hug. She would then start chatting, also in a rush, before proceeding with her work or to greet someone else. Helen was a most sincere person.”

Of her friend Helen, Marion Laserson remembers: “I knew Helen well. She was often at my house; at least once a month and sometimes even three of four times a week. Sometimes she was in a rush to go somewhere else and sometimes she needed my knowledge of computers. In the early 1990s she took it upon herself to promote the Johannesburg Historical Foundation. Helen got the idea that this amazing thing called a facsimile machine would be the way to go. So she would come to my house with a list of all the local publications and a hand written notice for the event. I would then produce the notice for her on my computer – always several times while she supervised every underline, colon, spacing, etc. – and she would sit at my fax machine sending out these notices to about twenty different publications. It took half a day. She also promoted the Shakespeare society in a similar way.

Illness barely slowed Helen down. One always felt that there had been a cyclone around when she left”.

Marion sadly passed away herself not long after writing this, on 11 July 2020.[1]

In 1980 Helen published a limited edition of a portfolio titled Witwatersrand Heritage Commemorative Issue… portfolio one .. Crown Mines est. 1909; this comprised four sepia toned photographs of the Crown Mines site taken by her in 1972 plus a folio page about the establishment of Crown Mines Ltd and its later history and a final reproduction of the share certificates. Franco Frescura designed and handled the lay-out of the historical information sheet. It was a limited edition of 1000. The somewhat nostalgic look was achieved with the decorative, overly elaborate scroll borders, giving the set the appearance of a modern day adaptation of an illuminated manuscript. But the photographs convey a severe and sombre mood. My favourite of this selection is the image of No 15 Shaft headgear at Crown Mines, with wild Highveld African grass in the foreground. The light and shade is the grass giving that look of abandonment of an old mine property. Crown Mines became the site of Gold Reef City and that faux heritage re-creation of Johannesburg circa 1890. That was heritage as fun fair and entertainment! Helen did not approve.

[1] [A similar tribute to her is scheduled to appear in a future Jewish Affairs issue – Ed.]

Crown Mines, Johannesburg (photograph: Helen Aron)

In the 1990s, Helen was an active member of the Johannesburg Historical Foundation with Alan Bamford. She was in charge of publicity and marketing the lectures and talks and reaching the newspapers. Her name appears in the annual reports and the journals of those years. Johannesburg Heritage Foundation was very grateful to Helen for her recent donation of a brand new copy of the Parktown Portfolio, which we sold at the Fund raising auction in December.

Rest in Peace Helen - your passion for your city will be remembered. We have lost a pioneer in heritage and conservation.

Helen Aron at the Holocaust Museum, Johannesburg, 2019 (photographer Gail Wilson). This photo captures Helen’s mood and sadness in response to the visit to the Museum. Lewis Levin was the architect. Here the exterior façade is clad with “railway lines” and stones embedded in the concrete. Railway lines, transportation to death camps and cattle trucks represented the journeys of so many Holocaust Victims. The railway line images are not straight but are intended to show confusion of genocide. Helen’s parents in the thirties fled to South Africa to give birth to the next generation.