Dr Harold Behr is a retired child psychiatrist and group psychotherapist. He emigrated from South Africa to the UK in 1970.

.

I have often felt that the passing of my father, Jacob William Behr, deserved to be marked by more than just the statutory notification plastered on the notice board of his apartment block in Netanya. His heroic efforts to introduce Hebrew into the South African Jewish community and to build bridges between Jew and Gentile and between English speakers and Afrikaners have made me proud to be his son. Hence this brief tribute, written more than forty years after his death. As to the question, ‘Why now?’ I can only respond with a rhetorical question, borrowed from Hillel’s famous maxim: ‘If not now, when?’

Born in 1902 in the Lithuanian shtetl of Linkuva, J W Behr was the only child of devoutly observant parents. His father had been ordained as a rabbi and was a teacher in the local cheder, so it must have taken an act of considerable renunciation for his son to have embraced a secular identity as a young man. The family left Lithuania for South Africa in 1913 and settled in Benoni, a mining town to the East of Johannesburg, where his father obtained a position as shochet and taught at the local Talmud Torah. In 1925 both his parents died within a few weeks of each other. Having been nurtured in a scholarly milieu, he saw his future in education.

Jack Behr and his mother Leah Breine, in Linkova, Lithuania circa. 1912

A year later, Jacob married his half-cousin Betty Levin, and went on to train as a teacher at what was then known as Normal College, a teachers’ training college in Johannesburg. Along the way he acquired two MA degrees, one in English from the Transvaal University College (later the University of South Africa) and a second from Pretoria University, where he studied Semitic languages under Professor B. Gemser, a distinguished biblical scholar. His thesis was titled ‘The writings of Deutero-Isaiah and the Neo-Babylonian Royal Inscriptions’, a subject which, I gathered, wrestled with complexities surrounding the authorship of the Book of Isaiah. Professor Gemser and Jacob worked well together. My father helped him in the translation of a book of modern Hebrew short stories into Afrikaans and always spoke admiringly of his mentor. He was awarded his degree in Semitic Languages with distinction.

References for jobs tell their own story. A reference in support of his application for a teaching position from his professor of English Language and Literature describes him as “a close student, a sedulous worker, and very conscientious, one who should, if he does himself justice, prove a scrupulous and successful teacher of English. I can unreservedly support his candidature for the post he seeks.” Another reference from the Head of Department at the Witwatersrand Technical College in Germiston, where my father taught for two years, records him as having “rendered valuable service and his results have been excellent....He has a quiet, unassuming bearing with an ability to get the best results even from surly-natured students. I have found him of the greatest assistance,” the reference goes on, “and it is a pleasure to testify to his fine qualities.”[1]

The Second World War saw my father enlist in the South African Home Guard, the ‘Dad’s Army’ of those days. This would have involved him in the protection of public buildings and installations from attacks by fifth column saboteurs but as far as I can remember he never reminisced about those experiences. I later discovered that he had achieved the rank of lieutenant, suggesting that he could wield an authority in the outside world which stood in striking contrast to his laissez faire philosophy on the domestic front. To me, my sister Evelyn and my mother, conflict avoidance seemed to be his watchword. If my naughtiness ever crossed a line, which it frequently did, he would sometimes punish me with an angry silence which could go on for days.

My mother was quietly proud of her husband’s achievements but constantly berated him for what she saw as his lack of ambition. In her mind this betokened perpetual consignment to a lowly economic status inside the bubble in which White South Africans lived. As a master of Yiddish invective, she often called him ‘a nar’ (a fool) and ‘a luftmensch’ (someone with his head in the clouds). For his part, my father would retort, ‘Du lebst in a cholem’ (You’re living in a dream).

With hindsight they both had a point: my father’s solution to life’s problems was to put his head down and concentrate on performing his teaching duties to the best of his ability. The word ‘ambition’ was not in his vocabulary. In his spare time he would study Hebrew or Russian, work in pewter or etch in linoleum. My mother, on the other hand, dismissed that sort of thing. She believed that anything which did not have to do with the betterment of the family’s position was a waste of time and that no goal was out of reach provided one knew how to pull the right strings. He was the hard-working pragmatist, she the driven visionary.

Jack Behr as principal of Forest Hill Primary School, Johannesburg (circa 1955)

When it came to instilling in me a knowledge of Hebrew, my father was both patient and persistent. When I was about four or five he playfully introduced me to the dots and dashes of Hebrew vowels and the strange shapes of the Hebrew alphabet. Words like ‘sus’, (a horse), ‘degel’ (a flag) and ‘gamal’ (a camel) were linked with graphic pictures and made an indelible impression on me. Throughout my school years he led me through passages of biblical text and modern stories, occasionally yielding to my fretfulness but always returning the next day with a carefully prepared list of words or a chart of grammatical rules. By these means he set the stage for my Barmitzvah in an Orthodox Synagogue, coached me through Matriculation Hebrew and flagged up my lifelong interest in the Hebrew language.

As far back as I can remember, religious fasts and festivals received no more than a token nod from him. It was at my mother’s behest that we celebrated Passover, feasting well, tasting the requisite dishes, munching Matzos and reading from the Haggadah, and it was she who maintained the custom of lighting the Sabbath candles. Although he eschewed ritual and observance my father was deeply rooted in his Jewish identity. He was steeped in Jewish literature and his abiding passion was the study and teaching of the Hebrew language. He was also committed enough to Zionism to take his family to Israel, although it was my mother who was the driving force behind the move. Her dream was to benefit from the legacy of a land purchase made by her father, a fervent Zionist who had stipulated in his will that his land in Palestine (as it then was) would only pass on to those of his children who settled there.

My family never belonged to a synagogue, although on High Holy Days my father would shepherd us to services held in a temporarily converted school building. He knew his way through the Machzor but I have no memory of him actually murmuring prayers or singing along with the rest of the congregation. He would look around at the worshippers with mild curiosity, showing me ‘the place’ in the Machzor whenever I prompted him to do so but otherwise professing a lack of interest in the proceedings. He once wrote in a letter to me: “As you know, my going to ‘shool’ has only a social significance.” But he began that same letter with a traditional greeting written in impeccably-vowelled Hebrew: ‘Le-shana tova tikateyvu ve-teychateymu’. After I left South Africa for the United Kingdom in 1970 we became closer to each other, paradoxically, through the exchange of letters. Perhaps we both felt more comfortable with the written than the spoken word. He would write dry, humorous accounts of family life and would often enclose newspaper cuttings on topics which he thought might interest me, including book reviews, accounts of goings-on in the Jewish community and news items about South African politics. He also sent me the occasional copy of Jewish Affairs and Buurman, an Afrikaans publication [also published under the auspices of the SA Jewish Board of Deputies – ed.] dedicated to the promotion of Jewish-Afrikaner relations. I see him as having straddled two worlds during the course of his life, that of education, in which he found his true calling, and the introspective world of Jewish thought, which he drew upon for guidance. His literary creativity expressed itself in a handful of poems and short sketches which he submitted to the Hebrew magazine ‘Barkai’, his identity hidden behind the nom de plume of Yaakov ben Zwi. His cultural life was centred on the Histadrut Ivrit, an organisation devoted to the development of Hebrew in South Africa, in which he was actively involved. After his retirement he was content to spend his time with his family and his books, ‘pottering about’ as my mother might have put it. He coached Bernard and Rosemary, my sister’s two children, through their adjustment to the new Hebrew-speaking world in which they found themselves, and his pedagogic talents, infused with grandfatherly affection, were applied equally to Adam and Rafael, my own two children, during our biannual holiday visits to the family. Watching him with his grandchildren, and remembering my own experiences as his son, I have learnt that the telling of stories without the expectation of performance is the most wonderful way of educating a child into a love of language and literature.

In 1977, having said goodbye to South Africa after sixty four years in teaching, he began planning his own adaptation to the familiar yet unfamiliar world of Israel. He even set about acquiring the rudiments of Arabic. But his illness restricted him and he was limited to the company of his immediate family and one or two relatives who visited him in Netanya. One of these was his cousin, the poet Michael Ben Moshe, whose company filled him with pleasure and with whom he shared memories of their birthplace, Linkuva, with mixed emotions. My father, died at the age of seventy seven on 1 October 1979 in Laniado Hospital, Netanya, following a long history of coronary artery disease. The date of his death coincided that year with Yom Kippur, although that fact probably would not have meant much to him.

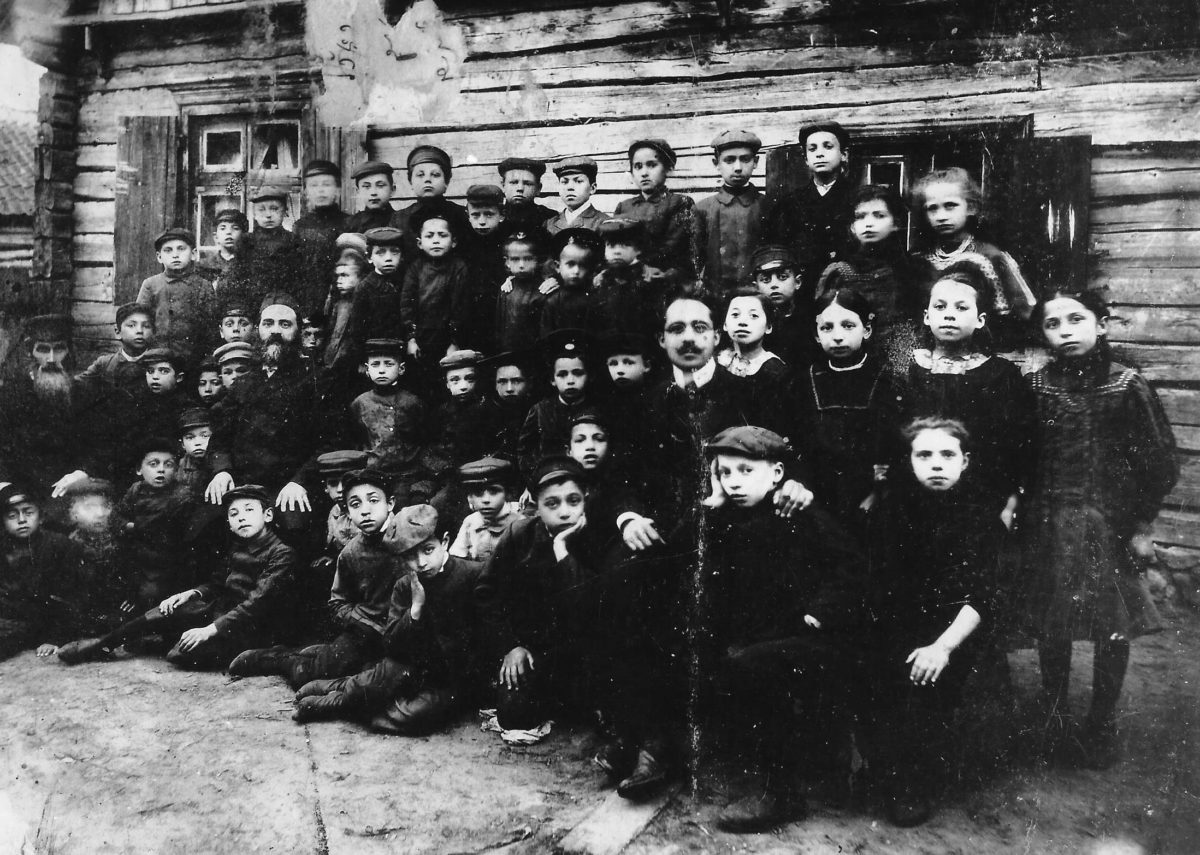

Cheder group, Linkuva (circa 1906). My father at centre with badge on cap. His father, Rev Hirsche Leib Behr, bearded, second teacher on left.

NOTES

[1] Yet another reference, written much later in his career by the man he was to succeed as principal of Forest Hill Primary School in Johannesburg, tells that “...He has a very pleasant manner with the children and has won their affection and respect. His discipline is effective and based on a positive rather than a negative approach. His contact with staff and parents has been marked by a tactful firmness and a readiness to co-operate....no class has passed through his hands without benefitting considerably...As far as the extra-mural activities of the school are concerned Mr Behr has, owing to the shortage of male members of the staff, done more than his fair share of the work, cheerfully and unselfishly.” And it ends, “Sorry as I would be to lose Mr Behr as Vice Principal of this School, I would like to see him obtain recognition of his abilities and qualities by well-deserved promotion.”