.

Marge Clouts was born and educated in South Africa. In 1961, she and her husband, Sydney Clouts, and their three children immigrated to the UK, where she taught English as a Foreign Language, English literature in various London colleges and Creative Writing in the Cotswolds. She has written many literary reviews for Jewish Renaissance and other publications.

‘...at his best, Sydney Clouts was the best: the most intellectually challenging, formally daring, and aesthetically sophisticated poet of the national corpus.’

This quote comes from Prof Dan Wylie's 2018 critical biography of the poet Sydney Clouts (1926-1982). The book is entitled 'Intimate Lightning: Sydney Clouts, Poet' after the title of one of Sydney's most remarkable poems. The above extract shows appreciation of a very high order.

Sydney and his twin brother Cyril were born in Cape Town in 1926. There were also two younger sisters, Jenny and Hazel. Their parents, Feodora (nee Friedlander) and Philip Matthew Clouts were cultured, public-spirited and very active in the Cape Jewish community and beyond. The brothers wrote adventure stories and poems as young boys, but as they grew older, Sydney became more absorbed in reading and writing poetry. He was greatly inspired by the poetry of Roy Campbell. Cyril turned to composing music.

After matriculating at SACS (South African College School), the brothers enlisted in the Union Defence Force, serving in the S.A. Corps of Signals. Both suffered from violent Jew-baiting from their 'brothers'-in-arms.

Sydney gained his BA at the University of Cape Town in 1950. His poems began to appear in small magazines such as Standpunte, Contrast, New Coin and Jewish Affairs. Prof Geoffrey Durrant was one of the judges in a 1954 poetry competition, and was sufficiently impressed by Sydney's work as to devote a complete episode of the SABC 'New Soundings' radio series to his poems, commenting, “I am delighted by the purity of their tone, the delicacy of their phrasing, and above all by the strength of mind - the firm foundation-rock of thought which makes the purity and delicacy possible...”

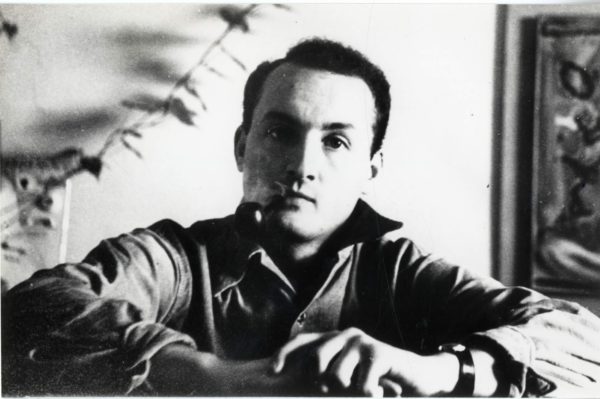

The young Sydney Clouts

More of Sydney’s poems appeared in South African anthologies. Prof Guy Butler of Rhodes University, Grahamstown, became a strong admirer of his work, and in time a most supportive and encouraging friend.

Another extract from Wylie's Critical Biography gives some idea of the quality of the poetry: “He brings to his craft an unusually deft and trenchant fusion of cerebral rumination and somatic responsiveness, of eclectic reading and gimlet-eyed observation of the material world.” Two early poems, with explicit Jewish content, may in part illustrate this:

RABBI AKIBA

.

Peacock-irradiant light

paraded the pines as the pine

branches brushed and bristled

continual blaze in the wind,

.

for a scholar's just replies

to twinge through the shade,

and halt me there with their learned

intensity and the fragrance

.

of his tangled fire, springing

in its brave complexity.

And then the reddest lines shook down

with blood upon their beard,

.

casual blood upon the beard,

and the wind burst down

with the passion of wisdom, the spray

of imperative blinding beams.

……...

THE EYE

Let it in, let evil in, the whole of it,

and rage is useless.

Millions done to death with grass in sight

and wheat and small cucumbers.

.

Grimly, how it loves the present age,

when the sun renews its being in the eye.

.

Blood's light behind distracts

more sunward than it dares

without me.

What am I without it,

in the dark,

the silent picnic?

.

Sandwiches and minerals

and lettuces for five

upon the rug, zigzag

of black and of vermilion, raging on the grass

that runs beyond, arriving centuries away

at fields and mounds of the dark ages.

.

Each century is different.

We have eaten,

we have drunk, in a new silence.

This time is sunflame out of evil

in the way we might have wished it,

for possession, seed by seedling,

of the knowledge of it,

out of passion for the pit;

and no one speaks

unless to joke.

.

What lovely scenery. . . .

.

Sydney was painfully aware of the violent excesses of Apartheid. He did not write 'protest poetry', but some of his poems of this period have intimations of disaster. A year after the Sharpeville massacre, he and his family (myself and our three sons) set off for London where Cyril and his wife Rose were already living. Sydney had gained experience as the manager of the International Press Agency in Cape Town, so the two of us started 'The Adamastor Press and Literary Agency' in London. By running the Agency from home, Sydney hoped to have more time to write poetry. (Adamastor was an invented mythical being, 'the brooding spirit of the Cape'. Roy Campbell also used 'Adamastor' as the title of his 1930 volume of poetry.)

In London, a number of young South African writers, many of whom regarded Sydney as their mentor, visited us. Numerous South African relatives and friends also visited, and some came to stay. Friday night Sabbath meals continued, large Seders were celebrated, and in due course three Bar Mitzvahs were held.

In 1966, Sydney's book of poems 'One Life' was published by Purnell and Sons in South Africa. For this the Olive Schreiner Prize was awarded to him in absentia - he himself was in London. For a poet so immersed in the memory and imagery of the Cape and South Africa, this separation gave rise to an acute sense of dislocation and exile. However, his award of the Ingrid Jonker Prize in 1968 was presented to him in London, at a gathering in his Cricklewood home by William Plomer and in the welcome presence of three other South African poets, Tony Delius, Uys Krige and Roy MacNab.

In 1967, Sydney's solo trip via Milan to Israel, and then joyfully to return to Cape Town to see his mother and other friends, was an exhilarating experience. In his short stopover in Milan, he was able to meet - very briefly - the poet Eugenio Montale, who he greatly admired; Israel 'bowled him over'. He travelled energetically up and down the country and spent time with the monk and poet Elias Pater 'in his cool monastery on the top of Mount Carmel'. Pater (originally a South African Jew) had read 'One Life' with 'such friendly thoroughness'. Between two long sessions of talk, Pater gave Sydney some of his own poems to read. In Jerusalem he walked and walked, finding it 'beautiful...unforgettable'. When walking toward the Mandelbaum gate, he got talking to Gad Levi, at that time senior editor on Kol Yisrael radio, who then introduced him to Chaim Gury, the Hebrew poet. (Sydney greatly admired the work of Bialik.) Any possible plan to make Aliyah was fraught with difficulties, particularly the need for Sydney, a poet devoted to the English language, to be in an English-speaking milieu. After some time in Cape Town, rejoicing in the sea and the pines, he visited Guy and Jean Butler in Grahamstown, meeting and charming the local literary circle. There the idea of Sydney getting a two-year administrative post at the ISEA (Institute for the Study of English in Africa) in Grahamstown) was first suggested.

In 1969 Sydney's gifts were recognised in Britain in the BBC series, 'The Living Poet'. A programme was devoted to his reading of some of his poems and his own comments on each. This was how he summarised the content and purpose of the long, important poem that he chose to read last: 'Blake's unfulfilled vision of England, the problem of race, a museum of relics, a small farm outside Cape Town, are some of the elements in my last poem which has an Afrikaans title, 'Wat die Hart van Vol Is' (What the heart is full of). The feelings of a South African in England, Europe and in his own country, and expressed in a personal meditation in which I hoped to achieve, with a directness of tone, a flexible rhythmic leap and return, the coiled spring.'

After considerable deliberation, Sydney decided to take up the administrative post in Grahamstown from 1969 to 1971. A conference entitled 'South African Literature in English', which he helped to organise, took place soon after he arrived. He participated in a poetry reading and met Alan Paton, Nadine Gordimer, Athol Fugard and other 'literary luminaries'. Sydney was truly in his element. He was also able to obtain his MA while there. His thesis was called 'The Violent Arcadia': an examination of the response to Nature in the poetry of Thomas Pringle, Francis Carey Slater and Roy Campbell' (three predecessor South African poets). He also had time to give many inspirational poetry readings.

After returning to London and his family in 1971, Sydney became a librarian. He made copious drafts of poems but published very little. In 1974 he felt very fortunate in being able to make another trip to South Africa under the auspices of the British Council, giving readings and lectures in many places. In a further trip in 1980, after time in Cape Town, he paid his last visit to Grahamstown, where he was as always much appreciated.

Sydney became ill in 1981. In July 1982, only a few weeks after insisting on struggling to Cambridge to see his youngest son Philip obtain his MA, he died of pancreatic cancer. He was only 56. A special edition of 'English in Africa' of October 1984 was entirely devoted to Sydney and his poetry. Now, an enlarged Sydney Clouts 'Collected Poems' is soon to be published, which will of course contain one of his most anthologised poems, called 'Poetry is Death Cast Out':

POETRY IS DEATH CAST OUT

Poetry is death cast out

though it gives one chance to retaliate.

Death takes it but the poem moves

a little further beyond death's gate,

and I know the proof of this. Once walking

amongst bushes and lizard stones I found

a little further than I had thought

to go, a stream with a singing sound.