Bernard Katz, a frequent contributor to Jewish Affairs is a Chartered Accountant who does freelance corporate finance advisory, investigations and sits on several boards.

.

The rise of Assyria, destruction of Israel and siege of Jerusalem

The opening verse of the Book of Isaiah places the life of the prophet Isaiah in its historical setting, which is the particular focus of this article: “The vision of Isaiah son of Amoz, which he saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem, in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah”.

Of all the prophets, Isaiah had the closest relationship to royalty. According to tradition his father Amos and King Amaziah of Judah were brothers (Megillah 10b), making Isaiah and Amaziah’s son King Uzziah first cousins. Isaiah’s activities and influence were at their peak during the reign of King Hezekiah, Uzziah’s great grandson. Tradition also relates that Hezekiah’s son Manasseh was responsible for murdering Isaiah (Yevamos 49b).

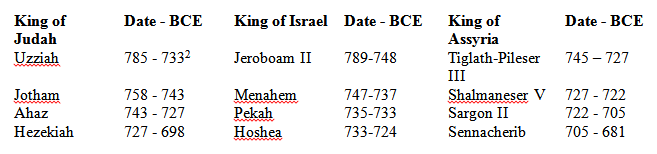

The table below provides the dates of the kings referred to in this article and in respect of the kings of Judah and Israel, as per the approach of The Biblical Encyclopaedia (editor Haim Tadmor, Bialik Institute, Jerusalem, 1962, Volume 4, Columns 301-302). The overlapping dates of King Uzziah’s reign are discussed further on.

Isaiah lived in a time of prophets – concurrently with Isaiah in Judah were Micah and Hosea while Amos prophesized in Israel during the time of Jeroboam II and Uzziah.

The Book of Isaiah is fragmented and not in chronological order. Much of it is obscure and abstruse and commentators have struggled with much of its content. While the book is characterised by chastisement, condemnation and rebuke it is counterbalanced by consolation, solace and hope. It also contains historical detail especially in relation to Isaiah’s dealings with King Ahaz and King Hezekiah.

Aspects of Isaiah’s life and the history of the period are also to be found in Kings and Chronicles.

The early prophecies of Isaiah stressed moral and ethical conduct and were severely critical of aberrant social behaviour and moral decadence; a rebellious people: “An ox knows its owner …but Israel does not know” (Isaiah 1:3), disdain for insincere offerings: “‘Why do I need your numerous sacrifices?’ says the Lord. I am sated with elevation–offerings of rams and the fat of fatlings” (1:11); evil behaviour: “remove the evil of your deeds” (1:16); dishonesty and corrupt business practices: “Your silver has become dross, your heady wine diluted with water….each of them loves bribery and pursues payments” (1:22-23); arrogance and haughtiness: “every proud and arrogant person and …every exalted person …will be brought low” (2:12); idolatry: “And the false gods will perish completely” (2:18); immorality and licentiousness: “Because the daughters of Zion are haughty, walking with outstretched necks and winking eyes; walking with dainty steps, jingling with their feet” (3:16); hedonism and debauchery: “Woe to those who rise early in the morning to pursue liquor, who stay up late at night while wine inflames them” (5:11); deceitful actions: “Woe to those who pull iniquity upon themselves with cords of falsehood, and sin like the ropes of a wagon” (5:18); injustice: “They acquit the wicked because of a bribe, and strip the righteous one of his innocence” (5:23); exploitation of the poor: “Woe to those … rob the justice of the poor… so that widows be their spoil; and they plunder orphans” (10:1), and decadent lifestyles “… [saying] ‘Eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.’” (22:13)

In the mid-19thCentury three ancient Assyrian cities – Nineveh (on the outskirts of modern-dayMosul), Nimrud (previously Calah – 30km south of Mosul) and Khorsabad (previously Dur-Sharrukin - 15km north east of Mosul) were discovered and excavated. A treasure trove of historical sources were unearthed which illuminate, clarify and contextualise the biblical account from an Assyrian perspective. In the words of Alex Israel, “The …wealth of archaeological and Assyrian records… verify, enrich and sometimes challenge aspects of the biblical account.”[ii]

The Geopolitical background

Around 800 BCE, about fifty years before Isaiah began prophesizing, Judah was an ailing state under hostile attack from King Hazael of Aram (also referred to as Aram-Damascus or Syria) and too weak to protect itself. The rise of a new superpower Assyria (situated in what is today the area around Mosul in northern Iraq) changed everything. Aram was forced to transfer its armed forces from its southern borders of Judah and Israel to its northern border with Assyria. This release of pressure on Judah and Israel enabled both kingdoms to survive.

With the threat of Aram removed, Judah’s economy thrived and it was able to build up its military strength. This allowed King Amaziah to reassert control over Edom and these territorial gains comprised copper and iron mines and important trade routes. For some inexplicable reason – being heady with success is given as one possibility - Amaziah challenged a reluctant King Jehoash of Israel to a battle (II Kings 14:8). The battle took place at Beit Shemesh, with disastrous consequences for Amaziah and Judah – Amaziah was defeated and captured, and as payment for this misadventure, Israel appropriated the Temple treasury (II Kings 14:11-14). During the 200-year period of the divided kingdom Judah and Israel didn’t clash often but four instances are recorded.

King Uzziah and a Golden Age

Uzziah replaced Amaziah as king of Judah and his reign as king of Judah (52 years according to II Kings 15:2) coincided with that of King Jeroboam II of Israel (whose forty-year reign was the longest by a king of Israel). This period, regarded as a golden age for both Judah and Israel, was characterised by expanding territory and enhanced security and prosperity, as well as peaceful relations between Judah and Israel. Judah’s territory grew by defeating Ammon and Moab to the east and the Philistines in the west whereas Israel defeated Aram and conquered Damascus. The important trade routes of the Via Maris (Derekh HaYam - between Egypt and Mesopotamia) and the Kings Highway (Derekh HaMelekh - from Egypt across Sinai to Aqaba through Jordan to Damascus) were both under the control of Judah. The security and prosperity achieved during this period had not occurred since the days of David and Solomon and would not come to pass again. Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein details archaeological finds dated to this period evidencing substantial building at Megiddo, Hazor and Gezer.[iii]

Isaiah began to prophesy around 750 BCE “in the year of King Uzziah’s death” (Isaiah 6:1) which most commentators interpret to be the year in which Uzziah contracted leprosy (which would be 758 BCE). This interpretation is necessary, for if the reign of Uzziah was indeed 52 years there would be no space for Jotham (16 years; II Kings 15:33) and Ahaz (10 of his 16 years; II Kings 16:2). Interpreting Uzziah’s death as meaning the year he contracted leprosy and abdicated in favour of his son Jotham allows for 26 years of Uzziah’s reign to run concurrently with those of Jotham and Ahaz.

As Uzziah became more powerful Isaiah expressed his concern about the immoral behaviour taking root - exploitation of the poor, income inequalities, greed, corruption and hedonism. According to biblical tradition Uzziah’s fall is attributed to his arrogance as well as his unwarranted interference in the Temple.[iv]

Kings records sparsely about Uzziah: that he reigned for 52 years (II Kings 15:2), did what was “proper in the eyes of Hashem….” (15:3), was afflicted with leprosy (15:5), and was buried with his forefathers in the City of David (15:7).

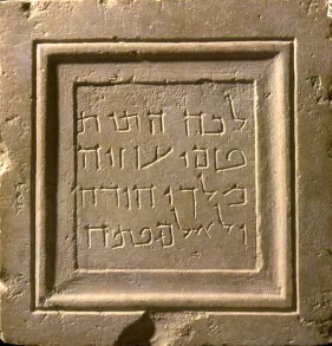

Chronicles provides more details, including that Uzziah extended the borders of Judah, built up and equipped the military, recorded victories over the Philistines, received tribute from Ammon and was exceedingly powerful. It also records that this power led to haughtiness, so that he entered the Temple to burn incense in place of the priests and as a result Hashem inflicted him with leprosy (II Chronicles 26). He was this “buried …. with his fathers in the burial field which belonged to the kings, for they said, ‘He is a leper’” (II Chronicles 26:23). The burial in Chronicles conflicts with Kings, where it clearly states that Uzziah was not buried in the City of David like the other Judean kings but in a burial field with belonged to the kings. Irrespective of where Uzziah was originally buried, it appears that his body was later disinterred and transferred to another place. This is evident from the Aramaic inscription now in the collection of antiquities of the Russian Church on the Mount of Olives which reads as follows: “Hither were brought/The bones of Uzziah/King of Judah/Not to be opened.”[v] Based on its language and script, the inscription has been dated to the end of the Second Temple times. Its provenance and the location of Uzziah’s reinternment is unknown but it was known in the Middle Ages in the time of Benjamin of Tudela.[vi] [vii]

Jotham, who became king when Uzziah contracted leprosy, is dealt with so fleetingly in II Kings and II Chronicles that it would appear that not much of significance took place during his reign. Nevertheless Jotham’s righteousness was venerated both in the Talmud and by Rashi, who said of him: “He had not a single flaw.”[viii]

Uzziah reinternment inscription - Israel Museum

King Ahaz and Tiglath-Pileser III

From the mid-8th Century BCE Assyria began to assert itself, becoming the unrivalled super-power threatening the entire region. The Assyrian people in all likelihood shared the same Semitic background as those of Babylonia and many researchers suggest that the origin of what historians more specifically refer to as the neo-Assyrian nation was population migration from Babylonia to Assyria after which a new independent nation was established, not dissimilar to the origins of America as an offshoot of Britain.[ix]

Tiglath-Pileser, a ruthless and capable man, was the effective founder of the neo-Assyrian Empire and enforced harsh tributes on the nations of the region. An inscription dated to 738 BCE lists numerous tributaries, including “Menahem of Samaria” and “Rezin of Damascus.”[x] [xi] Another Assyrian text also refers to Menahem: “[As for Menahem I ov]erwhelmed him [like a snowstorm] and he …fled like a bird….”[xii] The Bible records that King Menahem of Israel paid Pul (the Biblical name of Tiglath-Pileser III) a tribute (II Kings 15:19).

Around 734 BCE, the severity of the tributes led King Pekah of Israel and King Rezin of Aram to rise up in revolt against Tiglath-Pileser. They pressured King Ahaz of Judah to join the alliance but he refused.

Isaiah met with Ahaz “at the edge of the channel of the Upper Pool” (Isaiah 7:3). This would have been the outer open-air channel running from the Gihon spring along the Kidron Valley floor to a pool at the southern end of the City of David. It was later abandoned during Hezekiah’s reign and replaced by a tunnel leading to the Siloam pool. The visible traces of this channel mark its termination at the dry upper pool, “a mute witness to the dramatic encounter between Ahaz and Isaiah.”[xiii] Isaiah informs Ahaz of the plot of the kings of Israel and Aram to depose him and place the son of Tabeel (no doubt, a man with an anti-Assyrian and pro-alliance outlook) on the throne (Isaiah 7:3-6). Isaiah urges Ahaz not to join any alliances and advises him to be “calm and still; fear not”, disparagingly referring to the protagonists as “two smouldering stumps of firebrands” (Isaiah 7:4).

After being rebuffed by Ahaz, Israel and Aram attack Judah and “do battle against Jerusalem; they besieged Ahaz” (II Kings 16:5). In a precarious situation and despite Isaiah’s opposition to alliances of any sort, Ahaz appeals to Assyria for assistance: “So Ahaz sent messengers to Tiglath-Pileser king of Assyria, saying: ‘I am your servant and your son. Come up, and rescue me from the hand of the king of Aram and from the hand of the king of Israel, who are attacking me’” (II Kings 16:7).

The intervention of Assyria brings peace to Judah and its security is restored – neither Israel, Aram nor Philistia pose any military threat. But the price of peace was costly: “Ahaz took whatever silver and gold was found in the Temple and in the treasuries of the king’s palace, and sent a bribe to the king of Assyria” (II Kings 16:8). An Assyrian inscription dated 734 BCE records a tribute paid by “Jehoahaz of Judah” and other regional kings which included “gold, silver…linen garments with multi-coloured trimmings…all kinds of costly objects…the (choice) products of their regions….”[xiv] [xv] [xvi]

A further consequence of Judah’s vassal state status is that Assyrian cultural and religious practices were adopted. Although Assyria did not impose its religious and cultural practices on its vassals where these were found to be attractive they were introduced voluntarily. For this Ahaz is rebuked in the Bible: “He did not do what is proper in the eyes of Hashem….he even passed his son through fire….He [also] sacrificed and burned incense at the high places….” (II Kings 16:2-4). Chronicles also records that Ahaz “consigned his son to fire” (II Chronicles 28:3). After Tiglath-Pileser conquered Aram, Ahaz met him in Damascus where he saw an altar which he introduced into the Temple in Jerusalem (II Kings 16: 10-14).

Whilst the Assyrian inscription refers to King Jehoahaz of Judah, in the Bible he is referred to as Ahaz. Some commentators argue that the prefix Jeho, which is God’s name, was removed in the Bible due to Ahaz’s idolatrous behaviour.

Israel – the destruction of the northern kingdom

After the death of Jeroboam II Israel fell into decline – this period was characterised by political instability, assassinations and six kings in 25 years before the northern kingdom was finally destroyed.

Amos prophesized in Israel during the period that Isaiah prophesized in Judah and he railed against a debauched society where social injustice prevails and an immoral wealthy class exploits the poor:

“…Who oppress the poor,/Who crush the destitute,/Who say to their husbands,/‘Bring, and let’s party.’” (Amos 4:1)

“Who lie on ivory couches,/…Eating the fattened sheep of the flock,/…And anoint themselves with the choicest of oils.” (Amos 6:4-6)

The above-noted rebellion of Rezin of Aram and Pekah of Israel was quickly suppressed by Tiglath-Pileser of Assyria, and by 732 BCE it was over – a defeat from which neither of the rebellious parties would ever recover. Assyria’s conquest of Aram’s capital city Damascus is referred to in II Kings 16:9: “The king of Assyria went up to Damascus and seized it, exiling its [inhabitants] …and killed Rezin”. Tiglath-Pileser conquered the bulk of the territory of Israel on both sides of the Jordan, incorporating large tracts of it as Assyrian provinces while leaving mainly the mountains of Ephraim under the puppet king Hosea. The Bible records the Assyrian actions against Israel: “In the days of Pekah king of Israel, Tiglath-Pileser king of Assyria came and took …Hazor, Gilead, and the Galilee – all of the land of Naphtali – and he exiled them to Assyria” (II King 15:29). Chronicles 5:26 records the place names in the Assyrian Empire to where the Reubenites, Gadites and half the tribe of Manasseh were sent into exile.

Assyrian records reflect the events: “Israel (lit.: Omri-Land”) … all its inhabitants (and) their possessions I led to Assyria. They overthrew their king Pekah and I placed Hosea as king over them. I received from them …as their [tri]bute ….”[xvii]

After Tiglath-Pileser III died in 727 BCE, his son Shalmaneser V became king of Assyria. II Kings 17:3 records that Shalmaneser exacted a tribute from Hosea: “Shalmaneser king of Assyria went up against him; and Hosea became his vassal and sent him a tribute”. Sensing an opportunity to extricate Israel form the harsh Assyrian tribute Hosea sought assistance from Egypt: “Then the king of Assyria discovered that Hosea, had betrayed him, for he had sent messengers to So, the king of Egypt, and he did not send up his tribute to the king of Assyria....The king of Assyria then invaded the entire country; he went up to Samaria and besieged it for three years….the king of Assyria captured Samaria and exiled Israel to Assyria (II Kings 17:4-6).

In 722 BCE, near the end of the campaign against Israel, King Shalmaneser V died and was replaced by Sargon II. An inscription of Sargon reads: “I besieged and conquered Samaria, led away as booty 27 290 inhabitants of it.”[xviii] The destruction of the northern kingdom is dealt with extremely briefly in the Bible: “In the ninth year of Hosea the king of Assyria captured Samaria, and he carried the Israelites away to Assyria…” (II Kings 17:6). The year 722 BCE marks the end of the destruction of the kingdom of Israel and the exile of the ten lost tribes.

The number of deportees listed as 27 290 may seem relatively small, but Assyrian control and an influx of foreign populations made it impossible for Israel to reinstate itself as an independent entity. Significant emigration took place from the territories previously part of Israel to Judah, with archaeological evidence showing that by around 700 BCE, Jerusalem had expanded by three or four times its former size.[xix]

The Bible refers to foreigners being resettled in Samaria: “The king of Assyria brought [people] from Babylonia and Cuthah and Avva and Hamath and Sepharvaim, and settled [them] in the cities of Samaria in place of the Children of Israel….” (II Kings 17:24).

This matter is also referred to in an annalistic report of Sargon II: “I crushed the tribes of Hamud, Ibadidi, Marsimanu, and Haiapa, the Arabs who live, far away , in the desert ….I deported their survivors and settled (them) in Samaria.”[xx] This foreign population became known as Samaritans and their status is unclear – the matter has been debated as to whether they were genuine converts to Judaism who practised idolatry or gentiles who adopted some Jewish customs. The question of the Samaritans is discussed in the Mishna and later by the Tanna’im and there is disagreement on this matter – some consider them to be gentiles whereas others considered them to be Jews. But by the close of the Mishnaic period, there seems to have been a rupture between Jews and Samaritans.[xxi]

Israelite prisoners being taken into exile after defeat of the Northern Kingdom in 732 BCE – British Museum

King Hezekiah’s religious reforms

Hezekiah succeeded his father Ahaz as king of Judah in 727 BCE and is considered to have been amongst the greatest of the kings of Judah – second only to King David. “He did what was proper in the eyes of Hashem, just as his forefather David had done. He removed the high places, shattered the pillars, and cut down the Asherah-trees…. Amongst all the kings of Judah, there was no one like him, either before him or after him” (II Kings 18:3-5).

Hezekiah reversed the idolatrous practices of his father Ahaz’s era (II Chronicles 31:1), repaired the Temple (II Chronicles 29:18), fostered unity between Judah and the remnant of Israel (II Chronicles 30) and according to the Talmud promoted Torah studies (Sanhedrin 94b). Assyria was unperturbed about religion in the vassal states and archaeological evidence for these reforms were excavated at Tel Beersheba where a magnificent horned altar of hewn ashlar (forbidden under Jewish law: Exodus 20:22) was found, dismantled and incorporated into a wall. Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni who directed the dig believes that his Beer-Sheba altar was one of the altars which was dismantled as part of Hezekiah’s religious reforms. One of the stones has clearly engraved upon it a curling snake - a fertility symbol widely employed throughout the ancient Near East.[xxii]

One can well imagine Isaiah having a close relationship with Hezekiah during this period and playing a role in the reforms. Jewish tradition has it that Hezekiah was a star student of Isaiah’s.

The peaceful relations fostered during the reign of Ahaz between Judah and Assyria continued after Hezekiah came to the throne. Hezekiah became king in 727 BCE, the same year that Shalmaneser V succeeded Tiglath-Pileser III, and the policy of fealty to Assyria was maintained during his reign and the reign of Sargon II, who became king in 722 BCE. It was only after the death of Sargon II in 705 BCE, when Sennacherib became king that Hezekiah rebelled against Assyria.

Hezekiah’s foreign policy caused tension and later a split with Isaiah, who was vehemently opposed to rebellion or surrender. Isaiah was particularly incensed with Judah’s anti-Assyria alliance with Egypt (Isaiah 30:1-3; 31:1) and Babylonia (Isaiah 39) as well as the fortification of Jerusalem (Isaiah 22:9-11). The Bible reports that as a result of Isaiah’s despair he went “naked and barefoot for three years” (Isaiah 20:3). Maimonides claims that this was merely a prophetic vision and whoever thinks he actually walked naked and barefoot is of “weak mind.” Bin-Nun and Lau interpret the event as literal.[xxiii]

The conflict between Isaiah and Hezekiah with respect to international alliances was raised in a lecture given by Professor Yehuda Elitzur in Ben-Gurion’s series of Bible lectures (1965). Ben-Gurion raised the obvious question: “So faith requires us to eschew any covenant [with another nation]?” Elitzur replied: “Heaven forbid, Heaven forbid…right now, you are not worthy of being an empire.” Bin-Nun and Lau interpret this to mean that international treaties must be undertaken at the right time, and must stem from internal strength at home.[xxiv]

King Hezekiah prepares for Assyrian attack

In preparation for the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem Hezekiah covered up the Gihon spring located outside of the city to the east and cut a 533 metre tunnel through the hill of the City of David in order to divert its waters to the Siloam pool located within the city’s expanded walls. “He, Hezekiah, stopped up the upper source of the waters of the Gihon, diverting them underground westward, to the City of David….” (II Chronicles 32:30; II Kings 20:20). Today it is possible to walk through this tunnel – a half hour walk in shin-deep water.

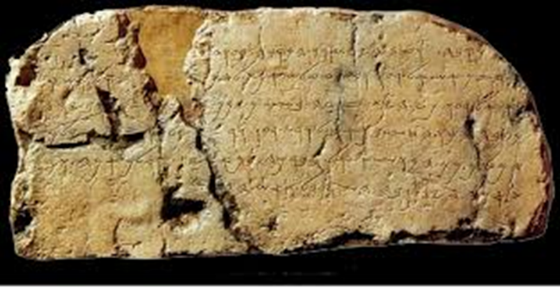

At the point where two teams met, tunneling from opposite sides, they celebrated their achievement by carving an inscription in the rock. The inscription, among the oldest records written in Hebrew, reads as follows:

“[…when] (the tunnel) was driven through. And this was the way in which it was cut through:- While [they were] still [excavating with their] axes, each man toward his fellow, and while there were still three cubits to be cut through, [they heard] the voice of a man calling to his fellows, for there was a fissure in the rock on the right [and on the left]. And when the tunnel was driven through, the quarrymen hewed (the rock), each man toward his fellow, axe against axe; and the water flowed from the spring toward the reservoir for 1200 cubits, and the height of the rock above the head[s] of the quarrymen was 100 cubits.”[xxv]

This Siloam Inscription was accidentally discovered in 1880 by Jacob Eliahu, a 16 year-old son of Jewish converts to Christianity. A Greek trader heard about the find and roughly cut out the inscription, breaking it. He was arrested by the Ottoman police, who confiscated the inscription and sent it to Istanbul where it can be viewed in Istanbul’s Archaeological Museum.

Siloam Inscription - Archaeological Museum, Istanbul

Lachish

The Bible records that “Sennacherib king of Assyria attacked all the fortified cities of Judah, and captured them” (II Kings 18:13). It is the subject of an evocative and much quoted poem, The Destruction of Sennacherib, by Lord Byron: “The Assyrians came down like the wolf on the fold/and his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold.” Assyria’s attack on Judah quickly overran the countryside before besieging Lachish, the second most important city in Judah, and the last hurdle on the way to Jerusalem. Sennacherib destroyed Lachish in 701 BCE and was so proud of this victory that the throne room of his palace at Nineveh commemorated the conquest with huge reliefs carved on stone panels. These were excavated by Sir Henry Layard in the mid-19th Century on behalf of the British Museum, where the 13 panels now reside.

Excavations at Lachish have identified the siege ramp (first recognised by Yigal Yadin), as well as such items as scales of armour, sling stones and iron arrowheads at the foot of the city wall where the fighting took place. The relief shows the storming of Lachish, and includes siege ramps, siege engines (with battering rams) and infantry, attacking the city gate and wall. The Lachishite defenders, standing on the walls, equipped with bows and slings can be seen tossing stones and burning torches on the attacking Assyrians. The relief also depicts a gruesome scene of captives being impaled on the city wall and the sad scene of Judean refugees leaving through the city gate being exiled and Sennacherib on his throne.

Lachish panels, British Museum

The Israeli archaeologist David Ussishkin, who directed a dig at Lachish, is of the view that the detailed relief gives an accurate and realistic picture of the city and the siege – the strength of the fortifications and the ferocity of the attack.[xxvi]

Siege of Jerusalem

The Bible records that after Sennacherib attacked “all the fortified cities of Judah, and captured them” Hezekiah sent messengers to Sennacherib at Lachish, sued for peace and paid a tribute (II Kings 18:13-16). The harsh tribute did not seem to pacify Assyria. Sennacherib sent Rabshakeh from Lachish to Jerusalem, where he met with Eliakim son of Hilkiah (who was in charge of the palace), Shebna the scribe and Joah son of Asaph the recorder at the channel of the upper pool. Rabshakeh issues an ultimatum of surrender and deportation or conquest and death (II Kings 18:18; Isaiah 36).

Once the war between Judah and Assyria had begun Isaiah’s relationship with Hezekiah was restored and Isaiah becomes a source of consolation and encouragement (Isaiah 37). Isaiah urges Hezekiah not to be frightened by the words of Rabshakeh and to stand firm and promises that Jerusalem will not be captured (Isaiah 37:5-7). He sent a message to Hezekiah expressing his contempt for Sennacherib: “Because you provoked Me, and your arrogance has risen into My ears, I shall place My hook into your nose and My bit into your mouth, and I shall make you return by the route on which you came” (Isaiah 37:29; II Kings 19:28).

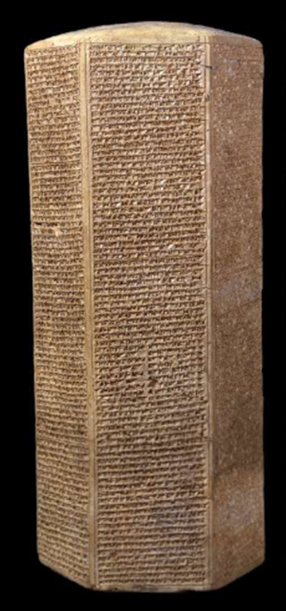

The Prism of Sennacherib, an hexagonal prism found at Nineveh, describes his military campaign in 701 BCE against Phoenicia, Philistia and Judah: “As to Hezekiah, the Jew…I laid siege to 46 of his strong cities…and conquered (them) by means of well-stamped (earth-)ramps, and battering-rams …. Himself I made a prisoner in Jerusalem, his royal residence, like a bird in a cage…. Thus I reduced his country, but I still increased the tribute…beyond the former tribute…”[xxvii]

Prism of Senacherib, British Museum

Despite the boasting language no mention exists of how the campaign ended. The Bible reports that a miraculous intervention resulted in the deaths of a major portion of the Assyrian army and so Sennacherib returned to Nineveh. “An angel of Hashem went out and struck down 185000 [people] in the Assyrian camp….So Sennacherib…returned…[to] Nineveh” where he was murdered by his sons (Isaiah 37: 36-38 and II Kings 19:35-37).

Isaiah (31:5) prophesizes: “Like birds in flight, so will the Lord of Hosts protect Jerusalem. He will protect it and deliver it. He will spare it and rescue it”. Could this be a direct retort to Sennacherib’s jibe at Hezekiah: “a prisoner…like a bird in a cage”? Alex Israel thinks so, adding that until the Assyrian documents were found it was not possible to appreciate the significance of Isaiah’s language. In his view these words of Sennacherib are one of Biblical archaeology’s most famous contributions to our understanding of Tanakh.[xxviii]

Seal impressions of King Hezekiah and Isaiah

Archaeological excavations directed by Eilat Mazar in 2009 in the Ophel discovered 34 bullae (seal impressions stamped on a piece of soft clay).[xxix] The Ophel is the area between the Temple Mount and the City of David and in Hezekiah’s time, David’s Palace in the City of David and Solomon’s Palace in the Ophel had already been functioning for 200 years. One of these bulla was impressed with the personal seal of King Hezekiah – the seal impression mentions his name, the name of his father and his title and reads as follows: “Belonging to Hezekiah, (son of) Ahaz, king of Judah.”

Seal of King Hezekiah

A few metres from the bulla of King Hezekiah there was found another seal impression which is thought to have belonged to the prophet Isaiah. This bulla is damaged and reads as follows: “leyesha’yah[u] Nvy[?]” – which translates into “[belonging] to Yesha’yah[u] prophet” – Isaiah being the Anglicised version. Mazar mentions that finding a seal impression of the prophet Isaiah next to one of Hezekiah should not be unexpected as no other figure was closer to Hezekiah than the prophet Isaiah. In the Bible the names of Hezekiah and Isaiah are mentioned together 14 of the 29 times that the name Isaiah is mentioned (II Kings 19-20; Isaiah 37-39). Mazar concludes that while questions still remain about what the bulla actually says given difficulties presented by the damaged area, the close relationship between Isaiah and Hezekiah, and the fact that the bullae were found next to each other, strongly suggests that the bulla belonged to the prophet Isaiah.

Isaiah's Seal (tentative)

Shebna

Shebna was one of the high court officials during the reign of Hezekiah. At one time he held the office as the “steward …in charge of the [king’s] house” (Isaiah 22:15) and in the famous scene where Sennacherib’s emissary Rabshakeh meets with the three representatives of Hezekiah, he is described as a scribe (II Kings 18:26,37; Isaiah 36:3,22). Isaiah is instructed to castigate Shebna for “that you have hewn yourself a tomb here … on high … and carves out of the rock an abode on the cliff” (Isaiah 22:15-16). In ancient Israel it was customary to be buried in a subterranean grave. Isaiah’s words imply that Shebna’s grave was conspicuously cut out of the rock-face, at a height, as was the practice of the aristocracy.[xxx]

In 1870 Charles Clermont-Ganneau, a French archaeologist excavated a partially destroyed tomb high up on the cliff overlooking the Kidron Valley and the City of David. Over the entrance to the rock cut burial chamber was an inscription that he could not decipher so he cut it out the rock and sent it to the British Museum where it still resides. The inscription was finally deciphered in 1953 by the Israeli epigraphist Nahman Avigad: “This is [the sepulchre of …] –yahu who is over the house….Cursed be the man who will open this.” Avigad’s argued (based on a suggestion by Yigal Yadin) that this was the tomb of Shebna/Shebnayahu mentioned in Isaiah even though the first part of his name is missing and only –yahu is preserved. He was able to date the inscription to the time of King Hezekiah by comparing its letters to the Siloam Inscription discovered in Hezekiah’s tunnel. Almost all scholars have accepted Avigad’s argument.[xxxi]

A damaged seal impression belonging to Shebna was found in a storeroom at Lachish in a dig under the direction of Israeli Yohanan Aharoni between 1966-1968. The seal inscription is damaged but has been identified as probably belonging to the same Shebna.[xxxii]

The Talmud (Sanhedrin 26a) records that Shebna headed a pro-Assyria party and treacherously betrayed Hezekiah by informing Assyria that he and his followers sought a peace agreement with them. This subversive behaviour no doubt also provoked Isaiah’s ire.

How many Isaiah’s?

Many scholars are of the opinion that the book of Isaiah as canonised must have been written by at least two different men. Chapters 1-39 by Isaiah ben Amos who lived in the eight century BCE and chapters 40-66 by another prophet who lived in exile in Babylon in the mid-sixth century in the days after its conquest by the Persian King Cyrus. This prophet is referred to as Isaiah II

Orthodox rabbis substantially view the Book of Isaiah as having been written by one prophet, and explain the time discrepancies by attributing the latter chapters to prophetic powers.[xxxiii] However, Abraham Ibn Ezra hints that because chapters 40-66 contain historical material subsequent to the time of Isaiah, it is likely that these chapters were not written by him and JH Hertz opines that this question can be considered dispassionately as is doesn’t impact dogma or any religious principles[xxxiv] etc. Yoel Bin-Nun is unconvinced by this hypothesis, arguing that during the Babylonian exile the Hebrew language was heavily influenced by Akkadian and Aramaic as reflected in the prophetic language of Ezekial. He maintains that the Hebrew of chapters 40-66 of the Book of Isaiah is entirely different to the Hebrew of the Babylonian exile.[xxxv]

Isaiah in Jewish Liturgy

The words of Isaiah are a daily companion during services and the most quoted prophet in the prayer book. Some of his most memorable words include:

“Blessed are You, Hashem, our God, King of the universe, Who gives strength to the weary” (40:29)

“Holy, holy, holy is Hashem, Master of Legions, the whole world is filled with His glory.” (6:3)

“For from Zion will the Torah come forth and the word of Hashem from Jerusalem” (2:3)

The Book of Isaiah has also contributed more haftarahs (15 out of 54) than any other prophetic book.

The Attraction and Legacy of Isaiah

The early prophecies of Isaiah are characterised by chastisement, condemnation and rebuke but they lay down a strong and unwavering moral and ethical compass of appropriate behaviour. This moral message expressed in succinct and sublime poetic language is as relevant today as when Isaiah proclaimed them 2700 years ago.

Isaiah counterbalanced his rebuke with words of consolation, solace and hope including: “The remnant will return” (10:21), “A staff will emerge from the stump of Jesse and a shoot will sprout from his roots” (11:1), “Behold, the king will rule for the sake of righteousness and the officers will govern for justice” (32:1), and “Comfort, Comfort My people” (40:1).

Isaiah could rightly claim his place as the poet laureate of the Jewish people and was possibly the first to issue prophecies relating to the concept of universal peace:[xxxvi]

“They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more” (2:4).

“The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, the leopard lie down with the kid, the calf, the beast of prey, and the fatling together, and a little boy shall herd them” (11:6).

Isaiah’s principles can be summarised in his declaration: “Zion will be redeemed through justice and delivered with righteousness” (1:27). His lofty idealism found expression in the State of Israel’s Declaration of Independence which reads: “The State of Israel …be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel.”

NOTES

[i] Israel, Alex, II Kings, In a Whirlwind, Maggid Books, 2019, p288

[ii] Israel, Alex, II Kings, In a Whirlwind, Maggid Books, 2019, p288

[iii] Finkelstein, Israel, Silberman, Neil Asher, The Bible Unearthed, The Free Press, 2001, pp 206-209

[iv] Bin-Nun, Yoel and Lau, Binyamin, Isaiah, Prophet of Righteousness and Justice, Maggid Books, 2019Bin-Nun and Lau, p39

[v] Views of the Biblical World, International Publishing Co. Ltd., Volume 4, p284

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Tudela, Benjamin, The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, Travels in the Middle Ages, Pangloss Press, Third Printing, 1993, p83

[viii] Quoted by Israel, op cit, p241

[ix] Kriwaczek, Paul, Babylon, Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization, Callisto, 2010, p210

[x] Pritchard, James, Editor, The Ancient Near East, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, Princeton University Press, 2011, p264

[xi] Cogan, Mordechai, The Raging Torrent, Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel, A Carta Handbook, 2008, p51

[xii] Pritchard, op cit, p265

[xiii] Cornfeld, Gaalyah, Archaeology of the Bible: Book by Book, Harper & Row, 1976, p152

[xiv] Prichard, op cit, p264

[xv] Views of the Biblical World, Volume 2, p282

[xvi] Cogan, op cit, pp56,58

[xvii] Pritchard, op cit, p265

[xviii] Ibid, p266

[xix] Broshi, M, The Expansion of Jerusalem in the Reigns of Hezekiah and Manasseh, Israel Exploration Journal, Volume 24, Number 1, 1974, pp21-26

[xx] Pritchard, op cit, p267

[xxi] Israel, op cit, pp276-278

[xxii] Horned Altar for Animal Sacrifice Unearthed at Beer-Sheva, Biblical Archaeology Review, March 1975

[xxiii] Bin-Nun and Lau, op cit, pp141-142

[xxiv] Ibid, p155

[xxv] Pritchard, op cit, p290

[xxvi] Ussishkin, David, Answers at Lachish, 40 By 40, Forty Groundbreaking Articles from Forty Years of Biblical Archaeology Review, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2015, Volume 2, p354

[xxvii] Pritchard, op cit, pp270-271

[xxviii] Israel, op cit, p301

[xxix] Mazar, Eilat, Is This the Prophet Isaiah’s Signature?, Biblical Archaeology Review, March/April/May/ June 2018, Volume 44, Numbers 2&3, pp64-73

[xxx] Views of the Biblical World, op cit, Volume 3, p48

[xxxi] Deutsch, Robert, Tracking Down Shebnayahu, Servant of the King, Biblical Archaeology Review, May/June 2009, Volume 35, Issue 3, pp45-49

[xxxii] Ibid

[xxxiii] Encyclopaedia Judaica, Keter Publishing House Ltd, 1972, 9:44

[xxxiv] Ibid, 9:46

[xxxv] Bin-Nun and Lau, op cit, pp213-214

[xxxvi] Y Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel: From Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile, Volume 3, Book 1, pp204-5 (Hebrew) quoted by Bin-Nun and Lau, op cit, p10