Gwynne Schrire, a veteran contributor to Jewish Affairs and a long-serving member of its editorial board, is Deputy Director of the SA Jewish Board of Deputies – Cape Council. She has authored, co-written and edited over twenty books on aspects of South African Jewish and Western Cape history. This is an edited version of her article, originally entitled ‘Immigration Restriction, Bubonic Plague and the Jews in Cape Town, 1901’ that appeared in the Chanukah 2008 issue of Jewish Affairs.

The advent of HIV/AIDS, the most extensive and fearful pandemic the world had known, made all previous pandemics pale in significance. Previously the most feared was the plague, from the Latin plaga meaning a blow, usually administered by a god.[1] The blow or blame has often fallen on the Jewish community. The Jews were made the scapegoat of the 1348 plague, or Black Death, resulting in extensive massacres throughout Europe. This article will examine what happened in Cape Town, when the 1901 plague reached it from the East.

People living in Cape Town, Muslims believed, would be safe from the plague because of a prophesy by Imam Abdullah bin Kadi Abdus-Salaam (Tuan Guru, 1712-1807), founder of the first madrassah in the city. He had foretold that all Muslims who lived within the circle of kramats (shrines) that encircled the peninsula would be safe from fire, famine, plague, earthquake and tidal wave[2]

But it was not to be so, because another great plague pandemic to befall the world reached Cape Town in 1901.

Considering the dread the pandemic instilled among the populace, the fact that it killed nearly twelve million people world-wide, and that it had local repercussions, it is surprising that there is so little reference to it in Cape Town Jewish history. Israel Abrahams, in his The Birth of a Community, makes what may be an oblique reference when complaining about the difficulty in obtaining sufficient matzah for Passover that year: “The war was still on and afflictions of all kinds were not in short supply, except – ‘the bread of affliction.’” As the first night of Passover, 15 April, occurred when the epidemic was at its height, it can be presumed that one of those ‘afflictions’ was plague.[1] The Cape Town Jewish Philanthropic Society appears not to have met during the epidemic because its minute book jumps from 24 February, when the plague began to take hold, to 9 June, when it was in retreat.[2] Neither Saron and Hotz in The Jews in South Africa[3], nor Dr Louis Herrman in The Cape Town Hebrew Congregation 1841-1941[4] mention the plague.

The omission is surprising, unless memories were short or the writers wished to gloss over something that reflected poorly on the community.

By this time, the role of heavenly bodies and righteous anger had been discounted as playing a role in the transmission of the disease. The responsible bacteria had been identified in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin, a student of Louis Pasteur, while working in Hong Kong. Yersin also noted that the disease was transmitted by rats.[5] The role of fleas was discovered three years later, but it was some time before this revolutionary idea was accepted, the prevalent belief being that the plague originated in filth and poor sanitation.

In 1898, the Bombay Plague Research Committee had defined the plague as a “disease which is essentially associated with unsanitary conditions in human habitations, the chief of which are accumulation of filth, overcrowding and absence of light and ventilation.”[6]

Compare this definition with the following contemporary descriptions of Jews in Cape Town:

Dwellings of the Jewish community are much overcrowded and ill-ventilated. These people herd together and overcrowd to an alarming extent. They are exceedingly afraid of fresh air and ventilation, and close every aperture in their rooms, notably when they have any illness. Their mode of living is objectionable and dirty in the extreme. They seldom ever bath and their bodies are covered with vermin.[7]

Cape Town… is full of those Polish Jew hawkers who live in dirtier style than Kafirs.[8]

The lowest class of Russian, Polish and German Jews, filthy and evil smelling.[9]

…the greasy dress of the Jewish refugee … the glimpses of indescribable dirt and squalor…through open doors and windows…[10]

...Jews, who overcrowd and cohabit promiscuously. Amongst them filth and vermin abound, and they have great objection to ventilation, the crevices all being wedged up with rags in many of their rooms. Some of these people are worse than the natives in these matters.[11]

Elizabeth van Heyningen,[12] a historian of the plague in Cape Town, believes that one of the factors behind the passing the following year of the Immigration Restriction Act, which limited the immigration of Jews and Indians, was the fears the plague aroused. As there was a perceived belief in the responsibility of Jews and Asians for the plague, the omission of the subject from local Jewish history is all the more remarkable. Immigration restriction had first been mooted at a plague prevention conference held in 1899, when the plague had reached India and there were fears that it might come to South Africa. One conference recommendation was that steps be taken to provide for the prohibition or restriction of immigration into South Africa from countries in which plague was prevalent.[13] The subsequent 1902 act was aimed, in the words of Governor Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson, at Asiatics, “paupers and persons suffering from ‘loathsome disease’”.[14]

Anti-immigration cartoon typical of what appeared in the early 20th Century South African media

One of the victims was this writer’s great-grandmother. On her recovery, adverse public opinion influenced the family to leave Cape Town and return to Europe.

The plague pandemic started in China in 1894, reached India in 1896 and arrived in Cape Town in 1901, spread by the British army during the South African War. The Cape Town harbour had been invaded by an armada of ships. Sometimes there were over 120 ships at anchor in the bay, many waiting months before they could be unloaded.[15]

The military took over the South Arm of the docks. In the ships arrived camp kettles, canned food and compressed cakes of tea, tents, clothing and tobacco, saddles, harnesses and hairbrushes, artillery, swords and guns. They offloaded horse shoes from Germany and Sweden, mule shoes from the United States[16] and horses, fodder and, inadvertently, ants from the Argentine (the latter soon made itself at home and replaced the local species, at considerable cost to the local fynbos.) From India, the ships carried boots, helmets and rats.[17] The rats carried fleas and the fleas carried the plague bacillus.

The war created employment opportunities both for labourers and call girls.[18] (“I went to the docks and the boats daily as a stevedore”, wrote one Eastern European Jewish immigrant to his wife, “There I worked for three weeks. In the first week I earned 8 roubles [16/-], the second week 16 roubles and the third week 20 roubles but I saw it would be the end of my health before that of my money and I could not carry on anymore”.[19]) There were 600 houses of ill fame in Cape Town. A brothel keeper complained that “he would not keep Jewish girls because they would not keep their places as quiet as French girls, and could not pay as much for their protection as the French girls”.[20]

The first cases of the plague, soon isolated, arrived in March 1900 on board the SS Kilburn from Argentina, which docked with its captain dead and three of its crew ill. They were all sent off to quarantine in Saldanha Bay, the matter was hushed up and the outbreak contained. In November, cases cropped up in King William’s Town among Africans, so that the belief arose that Africans were susceptible because of their unhygienic living standards.[21]

By September, dead rats started turning up in the docks, particularly in the South Arm, and dock workers began to fall ill. The Medical Officer of Health for the Cape Colony, Dr AJ Gregory, blamed “the old insanitary conditions of many parts of the city especially ancient storm water drains which created a labyrinth of rat runs”.

For the rats, Cape Town was a pantry. Unwanted waste from the fishing boats at Roggebaai and its fish market littered the shore-line. Untreated sewage ran into the bay. The offal from the Shambles (abattoirs), between the Grand Parade and the beach, was dumped in the sea nearby for the tides and the rats to dispose of free of charge.[22] Similarly, the refuse of Somerset Hospital was dumped twice daily on the beach by the assistant cook.[23] The Woodstock Station Hospital was no more sanitary. It was:

Badly situated on a flat stretch of beach close to the city and wedged in between the sea and the railway line. Moreover, the foreshore is not of the cleanest and the city council in its wisdom has constructed the sewage outfall in the immediate neighbourhood ... it lies in the teeth of the prevalent south east winds, which churn up clouds of dust.[24]

That wind called the Cape Doctor would blow the winter’s accumulated dirt into the ocean. Some areas of the city were never cleaned. Neither the City Council nor the ratepayers had the incentive to spend money on sanitation. Regular street sweeping and water-borne sewerage was only instituted by the City Council after the 1896 typhoid epidemic and the 1901 plague.

The war resulted in an influx into the city of refugees from the Witwatersrand, most of them penniless. As with the refugees from the 2008 xenophobic attacks, there was an outpouring of assistance from private individuals and communal organisations, but the arrivals only exacerbated the existing poverty and overcrowding. Twenty-five thousand people arrived between September and October 1899, of whom 3 000 were Jews.

“Next to Bombay, Cape Town is one of the most suitable towns I know for a plague epidemic”, stated Prof. WJ Simpson, the plague authority appointed to advise the government.[25] He reported that Cape Town had an extraordinary proportion of ancient and filthy slums, occupied by a heterogeneous population. The Africans were unfit for town life; the poorer coloured people were even dirtier in their habits, while the Malays and Indians possessed the habits of the Asiatic, and the poorer class Portuguese, Italians, Levantines and Jews were almost as filthy as the others. “Living in the same insanitary areas, often living in the same houses, the different races and nationalities are inextricably mixed up, so that whatever disease affects the one is sure to affect the other,” he wrote.[26] Jewish living conditions were identified as a contributory factor.[27]

Simpson did not believe that fleas transmitted the disease, but that rats became “infected by eating contaminated food, or by passing over infected clothing or places… Filth associated with darkness and dampness is peculiarly favourable to the growth of the microbe… Old dilapidated, dark, insanitary, and overcrowded houses… infected by rats are particularly dangerous. Rats and house vermin often carry the infection from dirty into clean houses.”[28]

The incidence of the plague was small at first, but the numbers of people affected gradually increased as did the virulence. In February 1901, Cape Town was declared an infected port, and the British Army stopped landing troops there. The deaths peaked in March, with 81 people hospitalised. By May there were about 33 deaths a week. The last plague victim was discharged from hospital on 27 November. According to the Medical Officer of Health, 204 whites were infected with the plague, with 69 deaths, 431 Coloureds (244 deaths) and 172 Africans (76 deaths).[29]

The Cape Town Hebrew Congregation’s 7th Avenue Cemetery in Maitland contains graves of Jews who died of the plague. All of them died at the Uitvlugt Plague Camp and all had “Bubonic Plague” listed as the cause of death. The 16-year old Barnett Berman died on 6 March 1901 followed two days later by 50-year old dairy man Samuel Kamenetz. They were joined in April by Judel Aberman (45), Sunder Freedman (24), Andrew Osoler (23) and Jacob Kaplan (60) and in May by a male pauper called Baker or Becker.[30]

The highest mortality was amongst the Coloureds, but it was the Africans who suffered the most, being blamed for its spread because of the association with lack of hygiene and because the first plague casualty was an African. Although there were 50% more cases of plague among the soldiers than there were amongst the civilian population, public criticism, blame and fear was not directed against the army, but against outsiders - the ‘other’. This was unjustified because the plague was introduced into the Cape by the military and the military was to blame for its spread through its negligence in failing to report the dead rats in the South Arm. It was also the military that was responsible for the disease spreading from the docks to the city through its camp in Green Point.[31]

But blame – and bigotry – is not always rational. Whenever plague struck, fear for one’s own life outweighed any concern one might have felt for the life of another and unfocused prejudice was directed at all strangers, including Africans, Asiatics and East European Jews.

The Cape Town City Council hired two more sanitary staff to clean the city, offered between 3d and 6d for a rat body brought to the incinerator (the Harbour Board offered sixpence per rat tail), and distributed handbills that emphasised cleanliness:[32] “For cleanly people in cleanly homes which are free from rats there is practically no danger of getting the plague…DIRT, OVERCROWDING, WANT OF VENTILATIONS AND THE PRESENCE OF RATS encourage the presence of Plague on any home or locality”.[33]

The Council’s half-hearted attempts to prevent the spread of infection by employing an additional two cleaners and issuing handbills did not satisfy the Government. Anyway, neither the rats nor the new immigrants could read English. The Government overruled the Council, instituting a Plague Board to enforce regulations.[34] This body’s first task was to set up a plague hospital (a site was chosen at Uitvlugt, near Ndabeni), and its second was to clean the city.

The number of cleaners was increased from two to 160 Europeans, 100 Africans and 280 convicts from the Breakwater Prison. These were offered a day’s remission for each day’s service – the work was hard, unpleasant and dangerous and there were fatalities among both the cleaning and the hospital staff.[35] Where a case of plague occurred the house was evacuated, hosed down with disinfectant, thoroughly cleaned and white-washed. Clothing and household effect were disinfected or, if too dirty, destroyed. Over 2 000 houses were demolished and rebuilt.[36] Those living in the infected houses and their contacts were inoculated and the rats and vermin killed.

The Parade, where many Jewish immigrants traded, had a bad reputation:[37]

Saturday by Saturday the ‘Grand’ - Heaven save the word - Parade gets worse. The rotten trash that is put upon the sale there would be a disgrace to Petticoat Lane. Not only this but the trade is now largely carried out by Polish Jews, who import the commonest off-scourings of Houndsditch goods. Then these frowzy gentry stand around... until whoever purchases is sure to be heartlessly swindled.[38]

The Plague Board banned public auctions on the Parade, causing many to lose a source of income.

As the plague had originated in the East, Asiatics were implicated. The San Francisco city authorities, refusing to accept the theory that the plague was caused by rats, blamed Asian immigrants and quarantined thousands. Only when that proved ineffective did they accept the rat theory, and killed 700 000 rats.[39] In Cape Town, there were complaints that the people who ran Chinese laundries and Indian and Chinese shops were oblivious to sanitation and cleanliness[40] and attempts were made to prevent the movement of Asians.

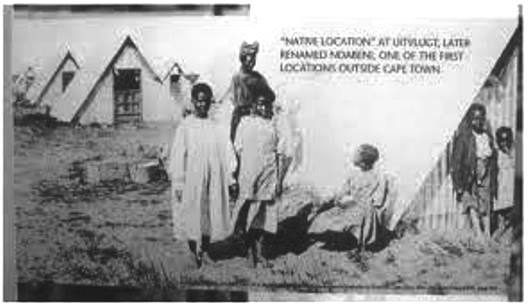

As the Africans were considered the most unhygienic, their homes were suddenly invaded by sanitary officers and police, their possessions confiscated and, like little Zipporah of Hameln, they were forcibly removed. This, plus the fact that they were being singled out, caused much dissatisfaction, particularly as they were not allowed to return to their homes to avoid the disease. Being told that it was all for their own good was of small comfort and those working in the docks went on strike. After a protest meeting was broken by mounted police, they were then moved under an armed guard to a municipal location established at Uitvlugt, Ndabeni, not far from the Uitvlugt Plague Camp. Others were sent to a location run by the Harbour Board below Portswood Lodge in the docks. This, the beginning of imposed racial residential segregation, was to be the forerunner of a pattern of locations, townships, reserves, group areas, black spots and Bantustans. There was an additional advantage in removing them to the Cape Flats because other people could now move into their previous homes, thus relieving overcrowding elsewhere.[41]

Forced relocation of blacks to Ndabeni location by British military, February 1901

Dirt and overcrowding was clearly stated in the handbills and messages as being factors encouraging the spread of the disease. Because of their alleged lack of hygiene, Jews were singled out. Dr. Gregory described Jews as being “often dirty in their habits, persons and clothing”.[42] The Wynberg district surgeon, Dr HC Wright, felt the cleanliness of the Africans compared most favourably with that of the Jews of the lower class. “No wonder Pharaoh found fit to ‘let the Children of Israel go’” he quipped.[43] In his 1901 Public Health report, Dr Wright complained that Jewish “houses are filthy in the extreme” and the children of “80 per cent of that persuasion bathed once a month.” The following year he reported that Jews “remain a sickly crowd, entirely oblivious to decency and sanitation. Many of their habitations are unfit to be used as such, and as they are large vendors of food, some serious notice should be taken of their mode of life and preparation and storage of articles of food.”[44]

In April 1901, some neglected District Six properties occupied by Africans and owned by Marcus Arkin in Vernon Terrace, Vandeleur Street, Mount Street and Caledon Street were condemned as unfit for human habitation. The Colonial Office took them over temporarily on condition that the government put them into a proper state of repair.[45] Arkin was prepared to evict the tenants on the very favourable terms offered by the government but Benjamin Levin, the holder of the second mortgage of the Vernon Terrace properties, objected.[46] When the Colonial Office returned the houses to Arkin in September, his lawyers instituted what Van Heyningen has described as an “acrimonious correspondence” over the condition in which the properties were finally left. She also noted that an examination of the street directories seems to indicate that the identifiable coloured names were replaced by Jewish names.[47]

My interest in the plague in Cape Town was first aroused when I was given a copy of my Great Uncle Harry Schrire’s memoirs. He had written:

There was an outbreak of bubonic plague in Cape Town at the end of the Anglo-Boer war, and my parents, who were considered fairly well-off with an income of £50 per month from rentals from the property in Harrington Street, decided to take a trip to Europe. They had been offered £5 000 for the property by a man called Kaiser but refused to sell because there was a boom at the time.[48]

Recently, I obtained a copy of an epic autobiographical Hebrew poem consisting of 150 verses, each having eight rhymed lines, entitled The History and Happenings, Reasons and Adventures, From the Day of My Birth, to the Day of My Death, with a Short Critique in a Clear Language, in Songs and Prose, in Remembrance for All Time. This was written around 1910 by my great-grandfather, Harry's father. Some verses described the plague and his decision to leave Cape Town. To my surprise, it contained information about his wife becoming ill. I showed the verse to a doctor, who identified the symptoms as possibly being of the plague. For the first time I realised that my great-grandmother, after whom I was named, had herself contracted the disease and that they had decided to leave because the community had blamed them. Here are the relevant verses in translation:

76) In the year Taf Resh Samech Aleph in the Boer War/People filled Cape Town like locusts/Rich and poor and immigrants/ They have traded in every trade./The prices of houses doubled/and like flies easily found gold /From buyers and traders and middlemen/ who came from all the corners of the country.

77) Since there were so many people, abandoned and crowded together/ the plague started to cut down the nation/ From under the ground, there were many small animals/ That were brought in ships from across the sea/ From dirt, neglect and lack of cleanliness/ Black and white fell fatally wounded/ Both the faint-hearted and men of vision/ dreaded death/ and walked like the shadows.

78) My wife was standing in the butcher shop/ when she noticed from afar the hurley-burley of the town/ As the wagon went by, painted red/ With the people working like devils against the disease/ In the sound of the congestion boys ran/ After the wagon that was taking the sick/ And she fell, fainted, without saying anything/ And her skin was covered with wounds and bruises.

79) She was almost dead and lay sorrowfully/ For about ten days in a critical condition/ And the moment she came out, her strength returned to her/ She saw the wagon with its canopy open/ And the whiteness of death covered her face/ And her illness returned with greater strength/ Her face became so swollen that her eyes could not be seen/ And she lay on her bed like a dead person.

80) When I saw from her that her disease was very bad/ and the quacks could not help at all/ She came to my business on her feet/ and the reproaches of the women fell on me/ “I was cruel”/ “I knew no mercy”/ “Even my small sons were suffering a lot”/ Then in the sorrow of my soul/ I swore in my anger

81) To leave Africa without returning…/

83) We passed the examination house with shaking knees/ Because the doctors of the town were examining every passenger/ And those who were forbidden to travel overseas… Only our possessions were taken…

[He details the destruction of their pillows, linen and clothes, but they succeeded in boarding the ship]

88) The disease attacked my wife again/ Through the night she became swollen as risen dough/ She slept without strength, as a dove she would moan/ And I could not call the doctor lest/ They would say the plague has started/ And I have worked hard to make her disappear from their eyes/ And my heart was sad that she would end and die like that.

89) Also she and her talking have pierced my kidneys/ because she believed they would throw her body into the sea….And to the servants of the ship…/ they believed that she had her period/ And I cleaned her room and changed her bed/ Changed her clothes from old to new.

90) …In two days/…we would come to London/ And her sickness has eased and her skin grew back/ And she had white freckles and scars…

91) With fear and trembling we went from the ship to the shore/ With ashes on her face and armpits...

Here is a first-person description of the conditions in the city when the plague struck and how it affected them in their butcher shop. The writer too accepts that the rat-borne disease was caused by “dirt, neglect and lack of cleanliness”, without the knowledge of the role played in its transmission by the random leap of a hungry flea. Boccaccio had complained that “no doctor’s advice, no medicine could overcome or alleviate this disease”– my great-grandfather would have agreed. He describes his wife’s symptoms, the panic in the street when the ambulance wagon chased by excited youngsters came by to take victims to the Uitvlugt Plague Camp, the criticism of their neighbours, the medical examinations at the docks and the destruction of their possessions that might have been contaminated. He describes their fear that the doctors might prevent them from boarding or leaving the ship and how they made use of ashes, in lieu of face powder, to disguise her scarred face and armpits (the glands affected by bubonic plague).

The 1901 plague had several results. Firstly the plague, according to Van Heyningen, gave respectability to the racism which was already entrenched. The unfocused prejudice was directed not only at Africans, but at almost every group which was poor and living in unhealthy conditions. The intolerance embraced all Asiatics, Russian Jews, Italians, Portuguese and others of Mediterranean origins and revealed a heightened jingoism which was not wholly indigenous.[49] Simpson, for example, thought the plague would have been stamped out had it also been possible to isolate in locations the Malays, the Coloured people and the poorer class of Europeans who were “seldom of British origin, but are foreigners from every part of the Continent, consisting largely of Portuguese, Italians, Levantines and Polish Jews”.[50]

Secondly, the Africans were removed from the city and placed in separate residential areas, a result of “a complex blend of prejudice, fear, expediency and paternalism”. They were the most severely affected and the biggest losers.

Thirdly, the prejudice equating Jews with dirt and disease made the climate more favorable to pass an act the following year to limit the entry to the Cape of these supposedly dangerous disease-harboring aliens.

Milton Shain held that despite suspicions that Jewish living conditions were a contributory factor to the epidemic, Jews did not receive differential treatment during the plague. This he attributed to the respect in which the Jewish establishment was held and the belief that the East European Jews were capable of improving with time.[51] However, the fear of contagion from these dirty East European aliens was more powerful than any respect given to the assimilated local Jews and provided a convincing reason to pass the Immigration Restriction Act hastily before the end of the 1902 parliamentary session.[52]

This was spelt out by Dr. Gregory, who said the Bill was aimed at the exclusion of Asiatics and, perhaps, Russian Jews, and should be framed to exclude undesirable persons by reason of their becoming a danger to the health of the community.[53] This association is clearly indicated in the words of a speaker at a protest meeting who said that the Colony was “infested from right to left with undesirable aliens.”[54] The subconscious choice of the word ‘infested’, one used for vermin, sends a clear signal.

Sadly modernity did not change this association. A Nazi propagandist, justifying the Final Solution, wrote:

A commendable achievement is also the far-reaching elimination of the Jews. If for instance Lublin, Lemburg and Reichshof during the last decades owing to the spread of the Jewish plague belonged to the most disgusting places of Middle Europe, now each of these cities, after the Jewish crust has been removed, … has thus again become congenial to the German.[55]

And finally, my great-grandparents moved overseas temporarily, where my great-grandfather met a young lady who, like him, was a keen Zionist, could speak Hebrew and had even corresponded with Herzl. My great-grandmother decided she would make a good wife for their eldest son, and as for their second son, my grandfather, he was left behind to study in Frankfurt, becoming the learned man I faintly remember.

NOTES

[1] Giblin, James, When Plague Strikes: the Black Death, Smallpox, AIDS, Harper Collinc, New York, 1995, 6

[2] Du Plessis, ID and CA Luckhoff, The Malay Quarter and Its people, Balkema, Cape Town,1953,33

[3] The boat carrying the matzot broke down and arrived late .Abrahams, I, The Birth of a Community: A History of Western Province Jewry from Earliest Times to the end of the South African War 1902, CT Hebrew Congregation, Cape Town 1955 p 128

[4] Minute Book of Cape Town Jewish Philanthropic Society 1897 - 1903, Alexander Papers, Archives of the University of Cape Town

[5] Saron,G, and Hotz,L, The Jews In South Africa: A History. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1955.

[6] Herrman, Louis, The Cape Town Hebrew Congregation 1841-1941, Mercantile-Atlas, Cape Town no date,

[7] Coppin, B, La Peste: Histoire D’Une Épidémie, Gallimand, Paris. 2000,42

[8] Quoted in Van Heyningen, E, Cape Town and the Plague of 1901, in Saunders, C and Phillips, H (eds) Studies in the History of Cape Town, Ed Saunders,C, Phillips,H, Van Heyningen,E (Eds) 4/1984.69

[9] Wynberg district surgeon Dr Claude Wright 1902 medical report, quoted in Shain, The Roots of Antisemitism in South Africa, 1994, 45

[10] Quoted in Shain, M, Jewry And Cape Society; The Origins and Activities of the Jewish Board of Deputies, The Cape Colony Historical Publications Society Cape Town,1983, 10

[11] Quoted in Shain, 1994, 51

[12] Cape Times 1908, Quoted in Shain 1994,52

[13] Dr C Wright, 1897, Quoted in Shain, 1994, 33

[14] Van Heyningen, 1984. p75

[15] Van Heyningen, 71

[16] Shain, 1983,23

[17] McKenzie, R (editor), Cape Journal, No 1, 1998,8

[18] Coetzer, Owen The Road to Infamy (1899-1900: Colenso, Spioenkop, Vaalkrantz, Pieters, Buller and Warren, William Waterman, Rivonia, 1996, 17-19

[19] The rats – and their fleas - might also have come, like the ants, from Argentina in the hay for the horses.

[20] The Salvation Army report, 1902, quoted in Hallett, R. Policemen, Pimps and Prostitutes- Public Morality and Police Corruption Studies in the History of Cape Town Saunders , C1/1984,pp 5,11,25,31 Some of the call girls were Jewish, as well as some of the pimps and brothel-keepers.

[21] Kretzmar, T, Unpublished letter, by kind permission of the late Dr J Kretzmar, Cape Town.

[22] Hallett, R., op cit, 31

[23] Van Heyningen, 73-5

[24] McKenzie, R, Cape Town Harbour, In The Cape Journal, 1, Cape Newspapers, Cape Town. 1998, 8,

[25] 1884 Rules and Regulations, Quoted in Laidler, P.W. & Gelfand, M, South Africa, Its Medical History 1652-1898 A Medical and Social Study, Cape Town,1971, 433

[26] The British Medical Journal, quoted in De Villiers, J.C. Hospitals in Cape Town During the Anglo-Boer War, South African Medical Journal, January 1999, Vol 89, No 1, p.76.

[27] Van Heyningen, 69

[28] Simpson lecture on plague, MOH 46 f668 22.5.1901 in Van Heyningen, 75.

[29] Shain, The Root of Antisemitism in South Africa, Johannesburg, 1994,45

[30] Van Heyningen, 79

[31] Ibid., 77

[32] For this information I am indebted to Paul Cheifitz, who surveyed and recorded the burials in the cemetery.

[33] Van Heyningen, 85

[34] The Cape Argus in August 2007 had an article about a job-creation project for the Men at the Side of the Road organisation that planned to train people to kill rats. The SPCA had complained because the method of killing the rats would have been cruel to the rats.

[35] Van Heyningen, 79

[36] Ibid, 80

[37] Ibid, 81-2

[38] McKenzie, R (ed.), The Cape Journal, Album 3, 1998, Cape Newspapers, Cape Town. 1998, 29

[39] My maternal grandmother’s father bought her a pair of shoes on the Parade when they arrived off the boats in 1904. When he came home, he found that both shoes were for the same foot.

[40] Shain, 1994,32

[41] Giblin, JC, 51

[42] Van Heyningen, 74

[43] Ibid, 98-9, 82

[44] Shain, 1994, 45

[45] Van Heyningen, 96

[46] He said that if the Government repaired the houses and placed coloured tenants in them, it would affect the value of the houses. Mr Levin demanded that the occupants be replaced with those of a more desirable class.

[47] Van Heyningen, 102

[48] Schrire, Harry, Unpublished memoirs, c 1960, type written manuscript in possession of his son, Arthur Schrire

[49] Van Heyningen, 75

[50] Ibid., 95

[51] Shain, 1994, 45

[52] Shain, 1984, 22

[53] Dr Gregory’s suggestions as to the framing of the Aliens Act 1902, Shain 1984, 25

[54] Said at a 1903 ratepayers meeting held to protest about Chinese, capitalists and aliens, Quoted in Shain, 1984, 54

[55] Dr Friedrich Lange, 1945, Quoted in Weinbreich. M, Hitler’s Professors: The Part of Scholarship in Germany’s Crimes Against the Jewish People. YIVO, New York, 1946, 168