Boris Gorelik is a Russian writer and researcher and faculty member at the Institute for African Studies - Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. He has an MA in linguistics from Moscow State University (2001).

.

The beginnings of the rooibos trade, one of the youngest tea industries in the world, were undistinguished. South Africans saw rooibos as an ersatz tea for the lower classes. Its quality was inconsistent, and both consumers and the industry regarded its absence of caffeine as a big disadvantage. The beverage was marketed as a cheap alternative to the imported product from China and Ceylon.

But the drink of need has become a drink of choice. Nowadays, rooibos is among the most popular herbal teas in the world and an important export item for South Africa. International celebrities champion rooibos drinking. Rooibos is costlier than mass-market teas: it is served in upmarket cafes and restaurants. Marketers talk of single-origin, or ‘estate’, rooibos, which commands stiffer prices.

Because of the initially low status of this beverage, its history was never researched comprehensively. Therefore, little is known about the Jewish contribution to the rooibos industry. In fact it was a Jewish family, the Ginsbergs, who helped to bring rooibos tea to homes across the country and pioneered its exports.

Benjamin Ginsberg, an immigrant from Russia, helped to turn a crude tea-like infusion, suitable only for boiling and stewing in a stove all day, into a modern product with reliable standards of quality. He was responsible for creating a unique and remunerative agricultural crop that brought financial benefits and increased economic security to many people in those dry, marginal farming areas.

Ginsberg’s story begins in Moscow, beyond the Pale of Settlement. The old Russian capital prided itself on being a thousand miles away from those areas. Few Jews had permission to reside in Moscow, but Aaron Ginsberg, Benjamin’s father, enjoyed that privilege.

At twenty-one, Aaron was called up. His regiment was quartered in Moscow and he had a rare opportunity to escape from the Pale once his term ended, as retired Jewish soldiers could make their home wherever they pleased. Several thousands of them had put down their roots in Moscow. Together with Jewish artisans, traders, hawkers and rag-and-bone men, they made up 3% of the city’s population.[1] Even if they could afford to stay only in poor areas, they preferred it to the squalor of the shtetls. Aaron’s hometown of Daugavpils (or Dvinsk as it was known at the end of the 19th Century) in the present-day Latvia looked far better than the typical Jewish villages, but he wanted another kind of life.

When Aaron was transferred to the reserve, he brought a bride, Elke, from his hometown. They were married in Moscow in 1885.[2] The couple started at the bottom, renting a flat in the city’s most notorious district. Such was its infamy that the streets were later renamed to blot out the memory of what was going on in Aaron’s time. The rent was low and – apart from pimps, prostitutes, drunkards, criminals and watering-hole keepers – the district attracted cash-strapped but respectable tenants like the Ginsbergs (as well as the soon-to-be-famous Anton Chekhov, who produced his earliest published stories there).

Benjamin Ginsberg's birthplace, Moscow

By the time Benjamin Ginsberg was born in 1896, his parents had realised that it was a wrong place to bring up their son, but Moscow could offer nothing better to them. After a year or so, the family returned to their native town of. There Benjamin spent his childhood and early teens. As you approached the town, you passed large forests of pines with crooked branches, interspersed with birches and spruces. The terrain was rather flat, with mist hovering over the river on bleak autumn mornings.

Dvinsk ranked among Russia’s industrial, commercial and railway hubs. Although some of the large companies were owned and managed by Jews, most of the Jewish residents were artisans, workers, clerks or small traders. Aaron made his living by embroidering carpets in the town, dubbed ‘Little Manchester’ for its bustling textile trade. Thanks to his skilled, highly paid occupation, he could rent a flat for himself, wife and nine children in a central middle-class district.

What made the Ginsbergs eventually leave Dvinsk and take the long journey to the Cape? Dvinsk saw no pogroms, although there were tensions between Jews and Gentiles. Possibly, Aaron did not want his six sons to be conscripted. His brother-in-law, Solomon Slavin, had departed for the Cape in the early 1890s, at the peak of Jewish emigration from the Russian Empire. Slavin settled at the south-western border of the Clanwilliam district and took up farming, supplying fresh horses for the Namaqualand postal coaches. He also opened a shop at the foot of Piekenierskloof Pass. It seems that he invited Aaron and Elke to join him once he had applied for his naturalisation papers.

Benjamin arrived at the Cape at the age of fifteen.[3] By that time, his father had become a general dealer and produce buyer. Apart from running the shop in that sparsely populated region, Aaron would deliver his goods to local farms. Many shopkeepers started as hawkers and peddlers, who moved around the district selling and bartering their wares. They served as liaisons to remote farms and villages, negotiating poor roads and treacherous mountain passes.

By 1904, the Ginsbergs had opened a coaching stop and trading post on the wagon road to Clanwilliam.[4] That old outspan place on the present-day Hexrivier farm – thirty kilometres south of the capital of the district, between the right bank of the Olifants Rivier and the Cederberg mountains – was called Rondeboschen. Aaron disliked the name and changed it to ‘Black House’. The locals, however, quickly dubbed it ‘Blikhuis’ (Tin House) because of the iron-sheet buildings that he put up.

Benjamin joined his father’s business and, being the junior partner, was entrusted with peddling trips in the area. At first, he visited his customers in the valley by foot. Later, when money started coming in, he drove a mule cart.[5]

Benjamin Ginsberg (1896-1944)

Imagine how different it all seemed to him, by comparison with his Dvinsk experience. There was no Jewish community to speak of, with a mere twenty-odd Jews in the entire district.[6] Instead of the plains and marshes, Benjamin saw a dry rugged landscape, of which many peaks remained unclimbed.[7] Instead of snow, there was sand under his feet. Instead of the rainy Latvian summer, he faced the scorching dry heat of the Cederberg.

Most locals were poor. They shared flour, coffee or sugar with their neighbours and slept on pine- or cedarwood beds with stretched thongs of ox hide as mattresses. People kept their clothes in large cedar chests and sprinkled a pinch of strong tobacco over them to keep moths at bay. Their floors smelt of dung, which they applied to the clay base every other week. They got around on donkeys, hitching two or three pairs to a cart or seven pairs to a wagon.

Goats gave them milk, bees gave them honey, and wild birds and rock rabbits were a ready source of meat. They baked scones in ash and enjoyed them with cold water to soften them up. They ate veld plants too, such as currant-rhus fruit or black candle-bush berries. If they got sick, there was plenty of buchu and other medicinal herbs.[8]

However, not everything was strange to Benjamin. His knowledge of Yiddish, with its Germanic words and grammar, helped him to get the gist of Afrikaans. Before long, he learnt to speak it without an accent.

The local tea-making ritual would remind him of home: like Russians, who had their samovars going for hours, people of the Cederberg region kept their kettles on the stove all day. Sometimes it was Asian tea which they purchased from Cederberg traders, or during their rare journeys to Clanwilliam or Cape Town. More often, they would have decoctions that they called ‘bush tea’. The kind that caught Benjamin’s eye was known as naaldetee, or ‘needle tea’. Some also called it ‘rooibos’.

The young salesman was introduced to it in the Grootkloof valley, ten to fifteen kilometres from Hexrivier.[9] He would have seen ‘stations’ on mountain slopes where Coloured pickers processed rooibos, buchu, kliphout bark and cedarwood before bringing it down to the village. When Benjamin and his father got to know rooibos tea, they added it to their product mix, buying from or bartering with pickers in the area.[10]

In 1912, after a decade in South Africa, Benjamin got married.[11] His young wife, Bertha Abramowitz, came from a wealthy Jewish family in Grodno, now part of Belarus. Having found herself living in Blikhuis, with its trading post by the old dusty road, Bertha felt uncomfortable. The middle of nowhere was not the place for her and Benjamin, she decided. The young family thus moved to Clanwilliam, where they opened their own small shop at the southern end of Victoria Street (now Visser Street).[12] Their first child, Henry Charles, was born in this town in 1913. The family did extraordinarily well for themselves in Clanwilliam, having transferred their business to fancier premises in Victoria Street, the current Clanwilliam Hardware.

Benjamin Ginsberg's shop in Visser Street, Clanwilliam

During the First World War, Benjamin began to consider the marketing potential of rooibos tea in earnest. It could find a ready market not just within the district, but elsewhere in the Cape and the rest of South Africa, because the imports of the Camellia sinensis from Asia dried up. The Ginsbergs probably knew about herbal teas in their homeland. The most popular hot beverage in Russia throughout the 19th Century was ivan-chai [13], an infusion made from the rosebay willowherb by people who could not afford Asian tea. Its narrow bay-like leaves were also used to counterfeit Chinese teas. If the raw material was unadulterated, the colour of the brew resembled that of the oriental product.

Rosebay willowherb was a common plant in that part of the world and, like wild rooibos, the plant thrived after fires. The more the Russian government raised duties on Asian tea, the more lucrative the ivan-chai industry became. In season, a family of peasants could produce over two tonnes. In the Petersburg Governorate alone, the annual yield of this herbal tea reached hundreds of tonnes.[14] The rank and file in the Russian army, like Aaron Ginsberg, were loyal consumers of ivan-chai.

The Ginsbergs would have also been aware of the crisis of the emerging tea industry in South Africa. Plantations in Natal had been recruiting thousands of pickers from India before the government put an end to it. The shortage of workers and capital forced many estates to abandon tea in favour of sugar.[15] The Ginsbergs could have reasoned that the diminishing output of Natal would not be much of a problem for the rooibos trade.

‘I’m going to make a Ceylon of the Cederberg’, Benjamin told his wife. He started buying rooibos from all over the region and encouraging farmers and pickers to deliver rooibos on a large scale.[16] His shop in Victoria Street became their offload site. This new side-line proved important to these farmers and pickers.

Anecdotes exist about Ginsberg’s early attempts to promote rooibos tea in Cape Town. They say, for instance, that he used to drop small packs of rooibos on pavements to be picked up by curious Capetonians.[17] His other (more conventional) approach was to put up stalls in Adderley Street and hand out free samples with instructions for making the tea. [18]

Standard Bank inspectors at Clanwilliam first recognised the existence of this ‘bush tea’ in their report of 1910. Throughout the following decade, they believed that another indigenous product of the district – buchu – showed greater promise. But as the popularity of the local tea grew, collecting buchu became a side-line to harvesting and processing rooibos tea.

Early rooibos pickers used to pluck or break the twigs off by hand.[19] Later, they started using knives or sickles. The sheaves of harvested tea were laid out on a flat surface and cut it into small pieces by means of hand axes, with handles made from hard, durable wood. ‘You put your left hand on the branches, grabbed the axe with your right hand and started chopping’, recounts 80-year-old Johannes Ockhuis of Heuningvlei. ‘The pieces had to be short enough to fit into a sack. It wasn’t a work for a couple of hours. You chopped all day.’ Afterwards, the pieces were crushed with heavy wooden poles or mallets (mokers), like the one on display at Clanwilliam Museum. In the evening, they moistened the batches of rooibos, covered or rolled them up in sack cloth and let the tea ‘sweat’ (oxidise) overnight. [20] ‘In the morning,’ continues Ockhuis, ‘you checked if the tea had turned brown. If you saw many green bits, you covered it again and let it sweat some more. Then, you removed the sacking and left the tea to dry under the sun.’ [21] On the following day, two people heaped the rooibos into a large sieve and swung it to and fro, until all the leaves slipped through and only the ‘sticks’ remained.[22] The tea would then be packed into sacks and delivered to the shop. When the picker reached the shop – with a bag of rooibos on his shoulder or across the donkey’s back – the tradesman would weigh it, give him the price and re-grade and re-sift the rooibos if necessary. The picker returned to the veld to fetch more tea, trying not to forget the amount he was due. He would be paid at the end of the week or month.[23]

Benjamin Ginsberg – one of the main wholesale buyers of rooibos – understood that if the market for it was to grow, this crude technology had to evolve. An urbane, cosmopolitan man, he got along with farmers and pickers, both White and Coloured, English and Afrikaans. At the same time, he could relate to what consumers in cities and larger towns required. Although he was a trader, not a producer, he had the knowledge and social skills to give momentum to the industry. Somebody, he realized, had to set quality standards for rooibos, as urban consumers expected a refined product, not a ‘poor man’s brew’. Furthermore, the Camellia sinensis industry had taught them to expect consistency in the tea they bought. If rooibos was hewn with a hand axe, how could uniformity of cut be achieved? With the primitive oxidising method, how could you guarantee a palatable taste and the intense reddish colour?

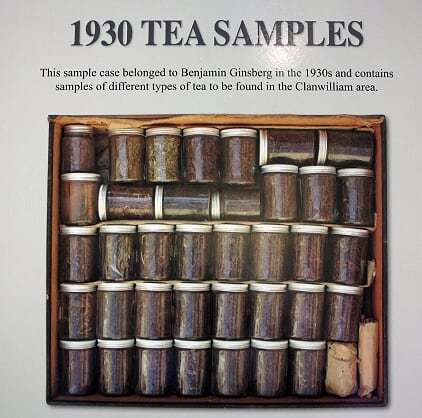

Benjamin’s black leather display case (pictured, left) of 38 bottles with different varieties of rooibos and herbal teas, each carefully marked, is shown in the Clanwilliam Museum. This artefact indicates his fascination with reviewing and establishing standards of quality for the Aspalathus linearis beverage.

Ginsberg helped to introduce chaff cutters and encouraged their use for chopping the tea evenly. [24] Pickers used to pull rooibos through the cutters like straw, as no machines had been especially designed for this industry yet. He also experimented with oxidation, sweating rooibos tea in barrels covered in damp sacking. By the end of World War 1, the A. linearis infusion had become a ‘fairly common’ beverage with ‘well-known tonic properties’.[25] This could have been a turning point for Ginsberg: in the next decade, rooibos tea became his company’s priority.

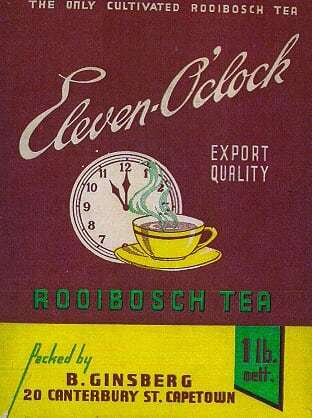

Most of the rooibos in retail was still offered loose and unbranded, and Ginsberg believed that a trademark was a seal of quality for the consumer. A rooibos with a recognised commercial name looked almost as attractive as the ‘real thing’, Camellia sinensis tea. Ginsberg already had his own brand of rooibos – Eleven o’ Clock – and constructed a packing facility next to his Victoria Street shop. The brand name gives away its colonial origin: the tradition of ‘elevenses’, a mid-morning tea with buttered scones, was cherished in the early 20th Century Cape. It was everyone’s welcome break on factories, farms and shops across Britain and the dominions.

Bertha Ginsberg remembered the day her husband pulled his watch from his waistcoat pocket, put it next to a piece of paper and drew a dial with the hands at eleven sharp.[26] You will still find that image on the packs of Eleven o’ Clock, the oldest existing brand of rooibos in the world. The Eleven o’ Clock packet also featured an illustration of a mother with the fashionable permed hairdo pouring a cup of rooibos for her young daughter in a gymslip dress. The image conveyed the message that packers of Camellia sinensis teas had been promoting for three decades: ‘Safe for the family’.

All rooibos was still collected in the wild. To satisfy the demand, farmers and pickers resorted to what we would today call ‘unsustainable practices’. Pickers cut rooibos bushes back so greedily that many of the plants did not survive. Another destructive method was patch burning. Tea pickers were aware that it sped up the regeneration of rooibos plants, which were the first to flourish before competing species overgrew them. But excessive burning brought about veld degradation and soil erosion. This alarmed Dr Peter Nortier, a Rhodes scholar who settled in Clanwilliam as the district surgeon. He believed that rooibos ought to be domesticated. ‘It would then become a non-paying business to rob the veld, and, in consequence, veld-burning would cease’, he wrote.[27]

With Benjamin Ginsberg’s encouragement, Nortier took it upon himself to convert the Cederberg tea into a proper agricultural crop. Ginsberg fretted about the future of the rooibos trade and the fact that annual yields fluctuated depending on whims of nature. Farmer friends of theirs, Oloff Bergh and William Riordan, provided the land for the experiments in cultivation. These four men – Nortier, Bergh, Riordan and Ginsberg – did more than anyone at the time to have rooibos grown and harvested in plantations, much like Asian tea. Although other industries in South Africa could borrow ideas from their overseas counterparts, the rooibos pioneers had to pioneer almost everything in their field. Nobody had tried to domesticate this tea elsewhere because it did not grow anywhere else.

The variety that the doctor developed – the Nortieria, or mak tee, cultivated tea – grows upright. Its lifespan is five to fifteen years, whereas uncultivated varieties can be harvested for decades – a wild rooibos bush was known to have yielded tea for half a century.[28] Yet, the cultivated variety has become the mainstay of the rooibos industry, enabling it to expand and provide jobs and income for hundreds of people in the rooibos-growing regions. Although less robust, the Nortieria is more predictable, delivering tea of consistent quality year by year.

Nortier’s goal has also been achieved: those who make a living from cultivated rooibos no longer need to burn the veld. Because the Nortieria cannot withstand the flames, farmers do their best to prevent wildfires from spreading.

The leading tea traders in South Africa showed no interest in rooibos until the late 1930s. The demand for rooibos tea was concentrated in the Cape, where consumers economised by mixing it with imported tea. In other provinces it was still a niche product, with low prices and sales volumes that did not entice the big companies.[29] Soon, that situation changed thanks both to the black tea shortages of the Second World War and the marketing prowess of Benjamin’s son, Henry Charles. Their company became the largest buyer of rooibos tea in the Clanwilliam district.[30] Once Chas Ginsberg had set up a sifting and packing factory in Cape Town, their tea was delivered directly to the city and marketed from there.[31]

In 1944 Benjamin Ginsberg died, aged 58. He was by then no longer just a country general dealer. He owned several properties in Cape Town and had accumulated close to an equivalent of today’s two million pounds in net assets.[32]

Chas Ginsberg inherited the family business and in the following decades, extended it countrywide. Most farmers still collected their tea in the wild, and he could not get the amounts that he needed. [33] That is why he went into farming. H C Ginsberg established the first large commercial ‘plantations’: his three farms in the Olifants River Mountains were producing half of the entire rooibos crop.[34] By the early 1950s, he was the biggest grower, buyer and marketer of rooibos tea.[35]

To break into the markets of Johannesburg and Pretoria, Ginsberg collaborated with Fred Smollan (incidentally, the second Jewish rugby player to be capped for the Springboks). Fred was also a founder of the present-day Smollan Group, a multinational corporation. With his brother, Len (also a rugby forward who played in the Transvaal squad), Fred pioneered field marketing services in Johannesburg. Chas appointed the Smollans as his agents in the Transvaal. Thanks to them, the first packs of Eleven o’Clock appeared in the Witwatersrand and the rest of the province.

Through Chas Ginsberg’s efforts, rooibos became available at every grocer’s across South Africa. For several decades, he served as Chairman of the Rooibos Tea Packers Association and on the executive of the Cape Chamber of Industry. He also served on the co-ordinating body of all agricultural Control Boards, representing the Rooibos industry and ensuring that all developments and refinements in agricultural crop management and planning and general agricultural Control Board functions were translated and communicated by its cooperative producers, representatives in the management of rooibos of this sensitive climate-unpredictable crop. [36]

His son, Bruce Ginsberg, introduced rooibos tea to the United Kingdom in the 1970s. He owns the bestselling British rooibos brand, Tick Tock, and continues the family tradition by offering his customers the iconic Eleven o’ Clock.

Notes

1 Y A Snopov, ‘Evrei v Moskve: dinamika chislennosti i rasselenie (XV-seredina XX v.)’, Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie. No 6, 2002, p 73.

2 Marriage register, 1885. Central State Archive of Moscow, fond: 2372, opis: 1, delo: 28 (chast 8), p 388 reverse, entry 28.

3 S Olivier, ‘A Russian custom brings a boom in rooibos tea’, Cape Argus, Magazine Section. 18 July 1964, p 3.

4 Bertha Ginsberg, interviewed by James van Putten, 1965.

5 Ibid.

6 Jewish Life in the South African Country Communities. Vol II. Johannesburg: South African Friends of Beth Hatefutsoth, 2004, pp 34-5.

7 G T Amphlett, ‘A Trip to the Cedarberg’, The Cape Illustrated Magazine. Vol VII, No 3, November 1896, p 66.

8 P Hanekom, Cederberg-stories uit Grootkloof. Cape Town: SilverSedge Books, 2015, pp 29-30, 84.

9 J W van Putten, ‘Die verhaal van rooitee’, Veld & Flora. September 1976, pp 28-9; A Ginsberg & Sons letterheads, Bruce Ginsberg personal collection.

10 Bertha Ginsberg, interviewed by James van Putten, 1965.

11 Benjamin Ginsberg’s marriage certificate. KAB, source: CSC; vol: 2/6/1/426; reference: 462.

12 Janette Marais interview, 10 March 2016.

13 S A Sadovsky; I A Sokolov, ‘Ne chayem yedinym... Neskolko slov o napitkah dochainoy epohi’, Kofe & Chai. No 4, 2014, p 29.

14 Ibid, p 30.

15 E Rosenthal, Old Time Tea Trade and Tea Growing in South Africa. [?: 196?], pp 60-9.

16 Bertha Ginsberg, interviewed by J van Putten, 1965.

17 Henry Charles Ginsberg, interviewed by J Van Putten, 1964-2000.

18 R Kenyon, ‘Rooibos: just our cup of tea’, Reader’s Digest. March 1987, p 27.

19 ‘Production of Rooibos Tea’, Farming in South Africa. April 1926, p 22.

20 Assistant Conservator of Forests, Western Conservancy, to Chief Conservator of Forests in Cape Town, 27 September 1907. KAB, source: FOR; vol: 28; reference: 1737.

21 Johannes Ockhuis interview, 27 October 2016.

22 P Hanekom, Diep spore: Petrus Hanekom gesels oor sy leeftyd in die Sederberge. Cape Town: SilverSedge Books, 2012, p 24.

23 Hanekom, Cederberg-stories uit Grootkloof, p 80.

24 Bruce Ginsberg interview, 16 December 2015.

25 Department of Forestry, Union of South Africa, Annual Report of the Department of Forestry. Cape Town, 1917, p 42.

26 Bertha Ginsberg, interviewed by J van Putten, 1965.

27 P L Nortier, ‘Soil erosion. District of Clanwilliam 1931’, p 5. Pieter le Fras Nortier Collection (MS 411), Special Collections, University of Stellenbosch. Document No 411.Pe.1(12), p 5.

28 Juweel van die berge: handleiding vir die organiese rooibosboer. Kaapstad: Environmental Monitoring Group, 2002, p 17.

29 General Manager of T W Beckett & Co Ltd to the Chief of the Division of Economics and Markets, Department of Agriculture and Forestry, Pretoria, 17 March 1937. SAB, source: LDB; vol: 1046; reference: R1212. T Simpson & Co, the sole agents for Mazawattee Tea for the Southern Africa, to the Chief of the Division of Economics and Markets, Department of Agriculture and Forestry, Pretoria, 17 March 1937. SAB, source: LDB; vol: 1046; reference: R1212.

30 Dr Peter Lefras Nortier, Clanwilliam, to the Principal of the Stellenbosch-Elsenburg College of Agriculture. SAB, source: LDB; vol: 1046; reference: R1212.

31 Thelma Harding interview, 12 March 2016.

32 Death notice. Benjamin Ginsberg. 1944. KAB, source: MOOC; vol: 6/9/10692; reference: 90492.

33 P J van der Merwe, ‘Baanbrekers in die Land van die Rooibostee’, Die Burger. Byvoegsel. 31 December 19490.

34 Olivier, ‘A Russian custom brings a boom in rooibos tea’, p 3.

35 ‘Farming personalities’, Farmer’s Weekly. 27 February 1957, p 75.

36 Bruce Ginsberg, email message, 29 December 2015.