Of all South Africa’s minority groups, the Jewish community is “among the most thoroughly dissected and psychoanalysed” observes Irwin Manoim at the beginning of Mavericks Inside the Tent – The Progressive Jewish movement in South Africa and its impact on the wider community, his ground-breaking history of the Progressive Jewish movement in this country. He could in fact have easily omitted the ‘among’ altogether,[1] but as a seasoned journalist probably decided to play it safe. Manoim’s point is that despite the plethora of publications on multiple aspects of the community’s history that have appeared over the decades, no proper history of Progressive (or, as it was long called, Reform) Judaism in South Africa has to date been written. His book, meticulously researched and compulsively readable (a rarity with institutional histories) thus fills a glaring gap in local Jewish historiography, but it also sheds light on a movement which, as the author correctly stresses, has been greatly under-valued in terms of the impact it made on the Jewish religious and communal scene.

Perhaps a explanation as to why it took so long for a detailed history of the Reform-Progressive movement to appear can be found in much of what appears in Manoim’s book itself. This relates to the remarkable frequency with which the Progressive community found itself convulsed by internal dissention, certainly from the early 1950s and to an extent before that. Of course, the Orthodox mainstream also had to deal with periods of conflict within its ranks (it took less than half a decade for the mother congregations of both Cape Town and Johannesburg to split, for instance), but this did not lead to the same degree of institutional paralysis, crises of leadership and fragmentation that the Progressive community was prone to. So bitter, prolonged and self-destructive were these confrontations that later Progressive leaders may well have preferred to allow the past to take care of itself rather than risk reopening old wounds. That a proper history has finally been produced is perhaps an indication of the movement having achieved a reasonable degree of internal peace and stability in recent years.

Manoim certainly does not play down the periods of internecine conflict that rocked Progressive Jewry and undermined its growth, and is forthright in identifying the factors that caused them. These ranged from failures of leadership, strategic missteps such as neglecting to take advantage of the opportunity to increase its membership provided by the influx of German Jewish refugees in the mid- to late 1930s, the failure even at the height of the movement to establish a Reform day school and the perenniel bugbear of regional turf wars, particular those conducted along north-south lines. As he insightfully writes, “The great fault line in South African politics falls somewhere between Johannesburg and Cape Town. Name almost any aspect of South African history and a Cape Town-Johannesburg dispute will be found”. This north-south cultural split, probably inevitably has also bedevilled Jewish communal affairs. One of the first really serious internal splits we read about occurred in the early 1950s and concerned Cape Town’s categorical rejection of a proposed creation of the position of Chief Minister under which all Progressive congregations would fall. Had that become a reality, the appointee would certainly have been Rabbi M C Weiler, the movement’s much revered and highly capable founding minister and spiritual head of its mother congregation, Temple Israel in Johannesburg. Much as the various Reform/Progressive congregations insisted on maintaining their autonomy, having a central authority authorised to represent and speak for the movement as a whole may well have made future internal disputes that much more manageable. As it turned out, comments the author, “Reform seemed a headless entity”, settling for the model whereby the movement was a “loose federation in which congregations made their own decisions and could pick and choose what central decisions suited them”.

Arrival of Rabbi M C Weiler (Rand Daily Mail, 31.8.1933): From left, Dr Louis Freed, Rabbi Weiler, Jerry Idelson, Max Franks

In addition, the debilitating ‘ chief minister’ controversy seems to have achieved what the previous twenty years of strident Orthodox opposition had failed to achieve, which was to demoralize and disillusion Rabbi Weiler himself. Later that decade, he would resign his position and make aliyah, despite only being in his early fifties. The Progressive movement would never again have a leader of his calibre, one who had been able to combine firm (bordering on autocratic) leadership within his own congregation with knowing even then when it was necessary to compromise and with the diplomatic skills enabling him to avoid or defuse confrontations with his own constituency and the wider Jewish community. Observes Manoim, he had somehow “managed to be a unifier rather than a divider, with a flexibility to change tactics, conscious always of never pushing too much beyond what he thought his constituency would tolerate”. The contrast in this regard between him and his successors is striking, particularly concerning Rabbi Adi Assabi who arrived in the late 1980s. While no less gifted and charismatic as Rabbi Weiler, Assabi became increasingly out of touch with key elements in his constituency in his singleminded drive to revitalise and ideologically remodel Progressive Judaism in South Africa and ultimately split the Johannesburg community altogether.

The fact that Rabbi Weiler carefully steered clear of confrontations with Orthodoxy and the mainstream community in general did not mean that he was compliant or compromising when it came to running his own congregation. In fact, in this regard he exercised a degree of authority that a good many Orthodox rabbis of those times would probably have envied. When it came to services, he insisted on strict discipline and decorum, especially during his meticulously prepared and often quite lengthy sermons. Indeed, when he was preaching the doors would be locked to prevent people wandering in an out, and children were expected as a matter of course to listen and behave themselves. At the same time, Rabbi Weiler knew when it was necessary to compromise, such as in agreeing to including the custom of breaking a glass at weddings and, more importantly, in retaining the barmitzvah ceremony at the traditional age of 13 instead of replacing it, as was done elsewhere, with a ‘confirmation ceremony’ at a later age. Had it been up to him, he would have dispensed with both, but he recognised that this not only would alienate many of his own congregants but would give ammuinition to those who accused Reform of being ‘inauthentic’. This combination of firmness and ideological consistency with pragmatism were essential to his success in establishing the movement on solid foundations, initially in Johannesburg and later in other centres. (Whether or not it was a mistake to wait until the movement in Johannesburg had been properly consolidated before looking to establish branches nationally is nevertheless a legitimate question, which the author discusses as well).

While the connection between the majority of South African Jews and traditional Orthodoxy at the time of Reform’s arrival was undoubtedly rather shallow and half-hearted, it is nevertheless highly unlikely that Classical Reform of the type then operating in the US and UK would have gained more than a handful of adherents had any serious attempt been made to introduce it in this country. The great majority of the community came from an East European background, where Reform was unknown, and the pull of tradition, even when limited to emotional rather than practical expression, remained strong. Weiler’s enduring achievement was to develop a mode of Reform worship, belief and practice suitably adapted to South African conditions. Sometimes referred to as ‘Weilerism’, this amounted to a new kind of Reform, one tailored to the inherent conservatism of the local community and which while “rather more cautious than the principles of his American and British counterparts” was quite radical by South African standards. Among the innovations introduced were that services would be in English and Hebrew with Sephardi pronunciation (which, as Manoim observes, was “in line with Zionist thinking of the time, but a radical step for a community with few Sephardis”), complete gender equality in terms of serving on synagogue committees and, over time, the introduction of the batmitzvah ceremony. Apart from English language prayers, these changes were eventually implemented by most Orthodox congregations as well. Other innovations, such as the replacement of Hazzanuth by professional mixed choirs were obviously not, although at that time the Orthodox Yeoville synagogue, albeit controversially, still featured a mixed choir – one of the immediate reasons, as it happened, why around this time a group of newly arrived German Jewish immigrants broke away from Yeoville to form what was probably South Africa’s first genuine Haredi community, the Adath Jeshurun Congregation. The latter developed into one of the main vehicles of the subsequent ‘Baal Teshuva’ (lit. “ those that return”) movement in Johannesburg from the late 1960s. Finally, and critically so far as making headway in South Africa were concerned, the local Reform movement has differed from its counterparts abroad by being fervently Zionistic from the outset.

Batmitzvah at Temple Israel, 1950s

A second major concern of the book inevitably deals with the periodic confrontations that erupted between the Orthodox establishment and the new religious movement that was challenging its hegemony. Indeed, as Manoim puts it, “a state of siege between Orthodox and Reform has been a characteristic of relations in Johannesburg for over 80 years, with only occasional moments of truce”. He adds that relations had likewise been tense in other centres (at one time, Reform had active congregations not only in Johannesburg (four), Cape Town (three), Durban, Pretoria, Port Elizabeth and East London, but in Bloemfontein, Springs, Klerksdorp and Germiston as well. Across the border in the then Rhodesia, there were for a long time congregations in Bulawayo and Salisbury), there had “been exceptions, particularly in smaller and more isolated communities where ‘sticking together’ has greater meaning”.

It is in fact arguable whether Orthodox-Reform ructions have played as much of a role in Jewish communal politics, even in Johannesburg, since at least the turn of the century. On the whole, things would appear to have been comparatively quiet on that front, one of the main reasons being that Orthodoxy, which confounded many sceptics by embarking on a sustained period of impressive growth from at least the early 1970s (not the 1990s as Manoim claims) no longer regarded the Progressive movement as a threat. This was certainly not the case, though, when Reform arrived in the early 1930s. That Jewish religiosity was at a dismally low ebb could not but be acknowledged by the disheartened rabbinical leadership of the day. Here Manoim quotes, among others, Chief Rabbi of the Johannesburg United Hebrew Congregation J L Landau, who lamented, “We are in a condition of moral and religious bankruptcy”, that the younger generation was “conspicuous for its absence from synagogue services” and therefore that the advent of Reform could “only result in completely alienating a number of younger members from Judaism”.

Apart from the then very small number of seriously practising Orthodox Jews, the mainstream Jewish leadership seemed to have objected to the new movement less for theological reasons than because of concerns over unnecessarily dividing the Jewish community – a regular refrain in Jewish communal affairs over the decades. To be fair, the advent of Reform did indeed, and inevitably, cause divisions, often flaring up into open confrontations. These were highly acrimonious, particular when they involved – as they often did – disputes over burial rights in Jewish cemeteries. Over time, compromises and accommodations were reached, sometimes by the local Reform/Progressive community (such as in Durban and East London) establishing its own Chevra Kadisha, at others by setting aside a separate section of the cemetery where burials could take place under Progressive auspices. There were also regular spats over the absence of Progressive teachings, and teachers, in the newly-established Jewish day schools, chaplaincy services for national servicemen belonging to the movement and, most of all, the right of equality of Progressive ministers in terms of reading prayers at major community events like SAZF and SAJBD conferences and Yom Hashoah. Here too, accommodations were arrived at over time but the Orthodox establishment, whose reach, influence and stature steadily increased as the post-war era progressed, actually conceded very little, and the much smaller Progressive grouping could only grudgingly accept whatever was offered.

Manoim delves deeply into the curious episode in local communal history, grandly termed at the time the ‘Casper-Super Concordat’ (1965). Theoretically, this was a mutually agreed-upon set of rules of engagement between the official heads of Orthodoxy and Reform, Chief Rabbi of the Federation of Synagogues Rabbi Moses Casper and the Chief Minister of the United Progressive Jewish Congregations Rabbi Arthur Saul Super. However, its real impact was not on what it purported to achieve (which in practice was to do little more than confirm the status quo) but on the disastrous fall-out for the Progressive movement as a whole. While lauded by the Jewish establishment (for example, the SA Jewish Board of Deputies termed it “a very sensible and practical agreement”, the Zionist Record expressed the hope that it would “mark the beginning of a new era of peace and dignity in the conduct of our communal affairs” and the SA Jewish Times congratulated both signatories for “their statesmanlike conduct”), it was widely regarded in Progressive circles as a capitulation (“a shameful document in which Reform formally acknowledges its own second-class status” as one critic put it). Apart from Rabbi Super being authorised to speak only for the three Johannesburg congregations – not that he claimed to be doing otherwise - and the fact that the Orthodox monopoly on officiating at public gatherings remained untouched, what was found to be especially objectional was the passage reading:

From the religious point of view there is an unbridgeable gulf between Orthodoxy and Reform. Therefore there can be no question of Orthodox Rabbis, Ministers or Chazonim participating in any Reform services, or vice versa; nor can there be any joint Orthodox-Reform religious services.

Super stated that this conclusion was arrived at “after a thorough examination of the Halachic situation and the Halachic principles involved”. His Cape Town counterpart Rabbi David Sherman by contrast said it amounted to “allowing ourselves to be read out of the community of Klal Yisrael”. As for the ‘unbridgeable gulf’, this was something that since Reform’s inception its ministers had striven to bridge. Thus did the movement again find itself seriously divided, against largely along north-south lines.

The preamble to Chapter 22 (all the chapters are usefully introduced with a short summary of the contents) asks whether there was “a match between religious liberalism and political opposition to apartheid”, the answer being “Yes, but…” This section uses as its starting point the role played by three Reform rabbis, Andre Ungar (see elsewhere in this Jewish Affairs issue), Richard Lampert and Adi Assabi. Manoim also reviews the more ambiguous activist career of the tempestuous Rabbi Ben Isaacson, who spent seven years in the movement before returning to his Orthodox roots, and the involvement of Rabbi A S Super. One concludes that while Progressive rabbis were far more likely to speak out than their Orthodox counterparts, their respective congregations were generally more cautious. Where the Progressive movement certainly did make a lasting difference was in the field of outreach, notably with the establishment, with the subsequent support by its United Sisterhood of the M C Weiler School in Alexandra and of the Mitzvah School on the premises of Beth David in Sandton during the turbulent late 1980s.

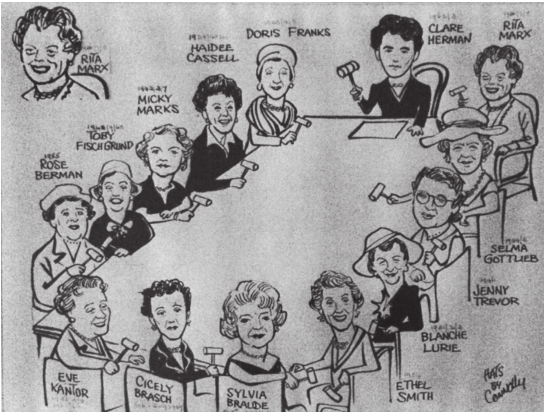

Portrait of United Sisterhood chairs, circa. 1957 by Bob Connolly (Rand Daily Mail)

Despite internal ructions, Manoim notes that at the time of its 50th anniversary, the Reform movement (as it was still called) was at its height in terms of numbers, resources and self-confidence. Much of what follows traces how badly things unravelled thereafter, whether due to self-inflicted blows like the Assabi fiasco or to factors beyond anyone’s control such as the white exodus following the 1976 Soweto Uprising, the effect of sanctions on overseas funding and what the author describes as “an unexpected surge of Orthodox religious zeal in the early 1990s”. Once an attractive option for young communitry members disenchanted with what it saw as outmoded forms of Jewish worship, the Progressive movement unexpectedly found itself losing many of its younger members to a resurgent Orthodoxy.

Two attitudinal surveys on SA Jewry, conducted in 1998 and 2005 by the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research at the University of Cape, showed the extent of the Progressive decline. In both, only 7% of respondents identified themselves as Progressive, less than half the percentage of the movement at its height (generally estimated to have been around 15%). Moreover, it was found that the Progressive membership was relatively aged compared to that of the Orthodox community. Writing in Jewish Affairs (Vol. 61, No. 3, Rosh Hashanah 2006), Shirley Bruk pointed to this “an unhealthy situation for the Reform/Progressive sector”, one that should worry those concerned with the future of the movement. The tendency towards under-representation of younger age groups and over-representation of older age groups had already been reflected when the first of the above-mentioned surveys were conducted, but had intensified seven years later.

Bnei Mitzvot ceremony, Temple Shalom, with Rabbi Walter Blumenthal

Given this downward trend, one would have expected the results of the next Kaplan Centre survey to show even further decline. Instead, they bear out Manoim’s observation that “after years of flagging membership, there are recent signs of a Progressive revival”. According to the latest findings, 12% of South Africa’s estimated 52000 Jews now identify as Progressive.[2] In Johannesburg the percentage remains at 7% but elsewhere it ranges from 18% in Cape Town to 25% in Durban.

How did this reversal come about? Much of it is due, as he writes, “to a younger generation of rabbis bringing renewed energy”. Even more important, though, had been the remarkable and wholly unexpected wave of conversions that have taken place under Progressive auspices, a high proportion of these being by people of colour, from roughly the beginning of this century. According to official figures, some 500 such conversions took place in the period 2002-2018, making up a high proportion of a total Progressive membership numbering around 5000. The 2020 Kaplan survey further found that converts make up 6.7% of the Jewish community and that of these, just under half (48%) were converted under Progressive auspices. Converts to Judaism in South Africa thus number roughly 3500, of which around 1700 are Progressive. Of those who converted, women outnumbered men in a 4:1 ratio.[3] If these figures are correct, than at least a quarter of Jews who identify as Progressive and perhaps more are, to use the expression now favoured by the movement, “Jews by Choice”. As the author concedes, “the widespread suspicion that the Progressive movement is heavily sponsored by conversion thus has some validity”.

Beyond mere numbers, converts (a growing proportion of who have not converted for purposes of marriage, or at least not solely for that reason) are revitalising Progressive congregations in other ways. Many are noticeably more committed and involved than their Jewish-born congregants and converts are disproportionately represented on synagogue leadership structures. With so many converts now in the system, many of them being “Jews of colour”, a process of “cultural hybridization” is underway. On the other hand, as Rabbi Greg Alexander of Cape Town’s Temple Israel is quoted as saying, “the steady influx of Jewish by Choice has camouflaged a serious problem: the lack of sufficient organic growth within the community”.

There are other serious long-term implications, not discussed by the author, of this burgeoning of the number of converts, and children of such converts, within the Progressive movement. When Progressive Judaism arrived in South Africa, in practice there was little to distinguish its membership from the Orthodox mainstream. As Manoim correctly puts it, “Almost the only thing that separated the ‘un-observant Orthodox’ from their Reform brethren was a label”. Thus, for the greater part of the local movement’s history, Reform/Progressive Jews could join Orthodox synagogues if they chose and, more importantly, there were rarely any obstacles to Orthodox and Reform/Progressive Jews intermarrying with one another. Increasingly, that is no longer true. Since Orthodox Judaism does not recognise Progressive converts, it follows that they do not recognise a substantial proportion of today’s Progressive community as being Jewish at all. Added to that is the fact that only those born to a Jewish mother are considered Jewish under Orthodox law, hence the children of Progressive converts (who, as noted, are mainly women) are likewise not recognised. The end result can only be that these two sectors of SA Jewry are destined in time to evolve into completely distinct communities, religiously and to a growing extent even ethnically distinct from one another.

Mavericks Inside the Tent is a lively, insightful, judicious and consistently readable exploration of Progressive Judaism in South Africa. The author has done an outstanding job in piecing together the story of this feisty, if often internally conflicted movement, one that while always a relatively small minority, played and continues to play a significant role in the greater saga of Jewish South Africa.

Mavericks inside the tent: The Progressive Jewish Movement in South Africa and Its Impact on the Wider Community by Irwin Manoim, University of Cape Town Press & Juta, 2019, includes photographs, glossary, bibliography & index, 528pp. ISBNs: 781775822646 (Print) 9781775822653 (e-PDF)

David Saks is Associate Director of the SA Jewish Board of Deputies and editor of Jewish Affairs.

[1] Good luck to anyone who wants to actually prove it, but in point of fact no other section of the population comes anywhere close to the Jewish community when it comes to writing about itself. In addition to the innumerable histories ranging from that of the community as a whole to that of just a small segment of it (just two recent examples are the histories of Brakpan and Potchefstroom Jewry by Mo Skikne and Paul Chaifetz respectively), there has been a continual stream of academic papers, works of fiction, demographic and attitudinal surveys and a growing body of publications of a purely genealogical nature relating to the community. To this can be added an apparently endless stream of biographies, memoirs and family histories. Jews appear to be especially keen on telling their own stories. Looking at Jewish political activists alone, those whose memoirs have appeared since the end of apartheid include Ben Turok, Norman Levy, Lorna Levy, Joe Slovo (posthumous), Ronnie Kasrils, Albie Sachs, Lionel Bernstein, Dennis Goldberg, Isie Maisels (posthumous), Rica Hodgson, Baruch Hirson and Raymond Suttner. No doubt that list could be added to.

[2] http://www.kaplancentre.uct.ac...

[3] Ibid.

Simchat Torah celebration in Cape Town, led by Rabbis Emma Gottlieb and Malcolm Matitiani