Paul Trewhela is a journalist, author and former anti-apartheid activists now living in Aylesbury, UK. From 1964-1967, he was imprisoned for his political activities, which included editing Freedom Fighter, the underground journal of Umkhonto we Sizwe during the Rivonia Trial. He has since written extensively on the lives of fellow Jewish political activists and other aspects of the liberation movement. He is the author of Inside Quatro: Uncovering the Exile History of the ANC and SWAPO (Jacana Media, 2009).

If a painter’s “hands are tied”, what happens to the painter, and the painter’s work? The phrase is Marc Chagall’s, writing about himself.

Standing alongside Picasso and Matisse, no artist of Chagall’s international repute in the 20th Century experienced such intense, specific and long-lasting censorship of his own free expression. He was the friend and colleague of nine (very likely ten) cultural figures – most, though not all, writers – who were specifically murdered or otherwise brought to their deaths by Stalin in the Soviet Union. His two surviving sisters and their families were living in Russia, and were very vulnerable, as were other friends. Chagall was never free of concern that anything he might do should threaten them.

Discussion of this crucial issue in his life and work is still grossly inadequate.

“My tongue is blocked,” Chagall wrote from France to Jewish friends in New York, Yosef and Adele Opatoshu, on 24 October 1950, at the height of Stalin’s antisemitic purge. (All his colleagues who perished over these years in the Soviet Union were, like him, Jews). “My hands are tied when I think about my poor friends and my sisters…” Concerning two of these writers “and others” then under arrest and interrogation, who were later executed, he wrote to the Opatoshus on 11 September 1951: “I certainly knew [them] very well.” Despite living and working in freedom, Chagall felt himself – and remained until he died - a hostage.

After February 1952, in a letter to the Opatoshus, he never again mentioned the names of these colleagues in writing. Thanking the Opatoshus that month for sending him a book of writings by the “Yiddish Russian writers,” he wrote, “It is a tragic document how Jewish life (there) is…I lack the words to think, to talk about our calamity, for we live in a world where the ground is missing.”

Five of those colleagues were executed in Moscow six months later in the basement of the Lubyanka on the Night of the Murdered Poets, 12 August 1952.

On 8 January 1953, Chagall wrote to Yosef Opatoshu, “every day of the new year we are waiting what ‘terrible’ news they will throw our way. …The last drop went over (even before the Prague trial).” He was referring to the trial followed by public execution on 3 December 1952 of 11 leading Communists in Czechoslovakia, nearly all of them Jews. The first public announcement of the so-called “Jewish doctors’ plot” appeared in Pravda on 13 January 1953, ahead of Stalin’s death on 5 March the same year.

Chagall’s beloved wife, Bella, had died in the New York in September 1944, where they had been living during the Second World War since escaping from occupied France in May 1941, following Chagall’s (brief) arrest in Marseilles as a Jew the previous month. In the middle of the profound crisis caused for him as friend, artist and Jew by the pogrom of Stalin’s last years, his partner of the previous seven years, Virginia Haggard (who was English and not Jewish), left him to marry another man in April 1952, taking away her and Chagall’s young son, David. The death of Yosef Opatoshu in October 1954 – through whom “I loved Yiddish literature and Yiddish writers, among whom he was the finest star” – then removed Chagall’s most intimate correspondent.

Whether in writing about him or exhibiting his work, there is a scandal of silence on the part of the art establishment relating to the crisis for Chagall at this time, with a particular focus on the killing of his Jewish friends by the Soviet state. Chagall’s experience over this period has no equivalent relating to any artist of his stature arising from Nazi Germany.

This is directly relevant to Britain because between June and October 2013, the state-funded Tate gallery in Liverpool staged a major exhibition, Chagall: Modern Master, with a superb collection of work ranging from Birth (painted by Chagall in St Petersburg in 1910, before his first sojourn in Paris) to the elegiac War, painted in France between 1964 and 1966, when he was nearly 80: a most moving evocation of the European tragedy of his lifetime. The exhibition included the seven surviving murals which Chagall painted on canvas in 1920 for the Moscow State Yiddish Academy Theatre (GOSET) in the pinched, starved period of Soviet “war communism”, for the Yiddish Theatre’s earliest productions.

Marc Chagall: Mural in the Jewish State Theater, Moscow, USSR, 1917-1922. (Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery)

During Stalin’s Great Purge of 1937 these specifically Jewish paintings were kept hidden. They remained hidden for 50 years, until well after Stalin ordered GOSET to be closed in 1949, and were not seen abroad until after the downfall of the Soviet Union. Chagall was nevertheless able to sign these large canvases in 1973 on his sole visit to Russia after he, Bella and their daughter Ida were given permission to leave the Soviet Union in 1922 by the Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky.

Almost certainly, that escape saved his life. He died in France in 1985, at age 98. In the Soviet Union he was regarded as a defector, and he dared not return to visit his family. None of his work was shown there after 1937, and the first full-scale exhibition of his work in Russia took place in Moscow only in 1987, on the hundredth anniversary of his birth, and only four years before the end of the Soviet Union.

Though no record has apparently been located so far in the archives in Russia, it is inconceivable that Stalin’s secret police and their successors did not keep a file on him. Major areas of Russian secret police archives have never been made public by the successor to the KGB. Yet barely a word of this period of intense trauma for Russia’s Jews, and for Chagall, appears in the otherwise well-produced catalogue for the exhibition, published by the Tate gallery in association with Kunsthaus, Zurich, which showed the exhibition prior to its showing in Liverpool, and where Chagall’s great painting, War, is housed.

The catalogue notes that the revolutions of 1917 “granted full Russian citizenship to the Jewish populace for the first time, dissolving the Pale of Settlement in the process. Chagall welcomed this new-found equality and the artistic revolution that was generated by the Bolshevik political revolution.” (p.134) Yet the catalogue provides not a single word of information about the circumstances in which “these masterpieces whose significance cannot be over-estimated” managed to “survive destruction during the Stalinist era” – its single, bland reference to the regime at whose hands five (almost certainly six) cultural colleagues of Chagall, who are mentioned by name in the catalogue, met a brutal death. (p.162)

Their deaths, and the manner of their deaths, are not even mentioned. This is despite the fact that the Selected Bibliography for the exhibition lists four books on Chagall by Benjamin Harshav – professor at Yale of comparative literature, of Hebrew language and literature, and of Slavic languages and literatures – which provide plentiful detail about these atrocities, and it lists also the voluminous biography, Chagall: Life and Exile (2008), by Jackie Wullschlager, chief art critic of the Financial Times.

An essay in the catalogue by Monica Bohm-Duchen, “Marc Chagall: Russian Jew or citizen of the world?”, makes no specific reference to the fates of these Russian Jewish colleagues, even though the murder and execution of two of them are mentioned in her study, Chagall (Phaidon, London, 1998), also cited in the Selected Bibliography.

The Tate catalogue notes that the “well-known actor Solomon Mikhoels” is “depicted numerous times” in Chagall’s mural, Introduction to the Jewish Theatre, which it reproduces in colour (pp.160, 164-65) It makes no mention that Mikhoels, who had been sent by Stalin to the United States with the poet Itsik Feffer in 1943 to raise support for the Soviet war effort, was specifically ordered by Stalin to be murdered in January 1948, the murder poorly concealed as a traffic accident, and covered up with a state funeral in Moscow.

Arrested on 24 December 1948, Feffer was executed in the Lubyanka with 12 other members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee on the Night of the Murdered Poets in August 1952. He and Mikhoels had had a brief, joyful reunion with Chagall in wartime New York in 1943. The following year Chagall provided drawings to illustrate a book of Feffer’s poems, which was published in New York. In her study, Chagall, Bohm-Duchen notes that Mikhoels and Feffer were “murdered by Stalin” – but says no more than that. (p.251)

Five other Jews also mentioned in the Tate catalogue with no indication as to their fate include Chagall’s art teacher as a youth in Vitebsk, Yehuda Pen, murdered at the age of 82 in his apartment in Vitebsk in 1937, “almost certainly by the NKVD”, as Wullschlager reports. Chagall, in France, had sent a letter to Pen a month previously, which Wullschlager notes was “kept by the authorities”. This suggests the possibility of a revolting revenge killing.

That fate came also to the dramaturge Yikhezekel Dobrushin, who adapted classical Yiddish works for GOSET, pictured with Bella and baby Ida at the far left of Chagall’s Introduction to the Yiddish Theatre: arrested in 1948 and died in the Gulag in 1953.

So too the writer Dovid Hofshteyn, who collaborated with Chagall on a book of poems and drawings, Troyer (Grief), arrested in 1948, executed on the Night of the Murdered Poets, August 1952.

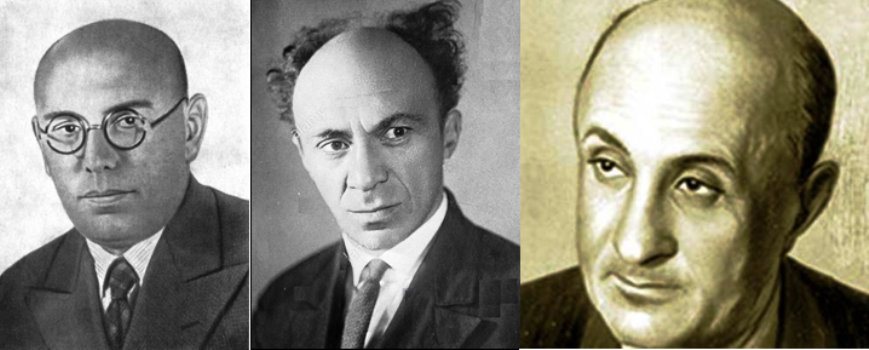

Victims of Stalin: Itzik Feffer, Solomon Mikhoels, Dovid Hofshteyn

So too the major writer of Yiddish fiction, Der Nister, who had worked with Chagall and Hofshteyn in an orphanage for homeless Jewish children whose parents had been killed in the pogroms of the civil war period: arrested 1948, died in a prison hospital 1950. (Chagall had illustrated his poems, and inscribed Der Nister’s name with those of other Yiddish writers in his Introduction to the Yiddish Theatre).

And so too also one of the most celebrated gallery owners and publicists of modernist art in Europe, Herwarth Walden, who brought Chagall to prominence before the First World War at his gallery, Der Sturm, in Berlin. A chapter in the catalogue on Walden, who was Jewish (his birth name was Georg Lewin), notes that as a gallery owner he represented a swathe of the most eminent European artists of his day, including Kokoschka, Klee, Kandinsky, Marc, Macke, Robert Delaunay, Leger, Henri Rousseau, as well as “the Futurists and others”. (p.31) In addition to not mentioning the manner of death of Mikhoels, Feffer, Pen, Hofshteyn and Der Nister – despite references to them in the text - the Tate catalogue neglects to mention that Walden fled from Germany to the Soviet Union in 1932, where he was arrested during the period of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and died in prison in October 1941.

In a letter for Walden’s 50th birthday in 1928, quoted in the catalogue, Chagall had expressed his “highest esteem” for his former patron, as the “foremost and fervent defender of the New Art and, particularly, as the first disseminator of my works in Germany.” (p.39) It was Walden’s fervent defence of the “New Art” in Stalin’s Russia which brought him to grief.

Of three other people whom Chagall knew, shot as “Jewish nationalists” in the Night of the Murdered Poets, one was the Yiddish poet and playwright, Perets Markish. Together with another Yiddish writer, Oyzer Varshavsky, Markish had translated Chagall’s autobiography, My Life, into Yiddish (with assistance from Chagall) while staying in Paris in the mid-1920s, and Chagall had illustrated the cover of a Yiddish literary journal co-edited in Paris by Markish and Varshavsky with an image of himself, Markish and Varshavsky seen climbing the Eifel Tower.

Also shot that night was the celebrated actor Benjamin Zuskin, who had acted the Fool to Mikhoels’s King Lear, taking over the directorship of GOSET after Mikhoels’s murder. Zuskin was in the garden of the Chagalls’ house near Paris in 1928, along with Mikhoels and the entire GOSET troupe, in a group photograph with the Chagalls shortly ahead of the defection of the GOSET director Aleksei Granovksy, pictured with his head held deep in his hands.

A third, the Communist and Yiddish writer, Dovid Bergelson – like Mikhoels, Feffer, Hofshteyn and Markish a leader of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee during the German invasion – was arrested in January 1949 and shot on the Night of the Murdered Poets. Chagall had visited him in Berlin in the 1920s, before Bergelson’s return to live in the Soviet Union in 1934.

This appalling experience of brutal loss has important consequences for the appreciation of Chagall’s later work, representing – in my judgement – many of the most powerful, resonant and universally meaningful images in the whole of his oeuvre.

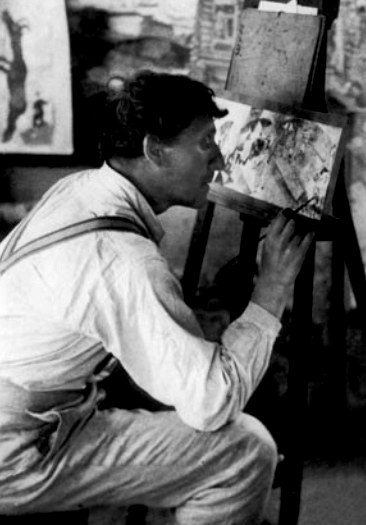

Marc Chagall painting Study for Introduction to the Jewish Theater (1920),

The central importance of the Crucifixion image in the paintings of the last half of Chagall’s life, with his numerous evocations of Jesus the Jew as emblem of a suffering humanity, and in particular of Jewish suffering, is now well recognised. A crucial, universalising development in Chagall’s conceptual and artistic development over this period came with his re-working of his canvas, White Crucifixion, painted originally in 1938, after the horrors in Germany culminating in the destruction of synagogues and killing of Jews at Kristallnacht. Following the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 1939, Chagall obscured his original painting of a swastika on the armband of a storm-trooper setting fire to a synagogue in the top right-hand corner, as well as the German text “Ich bin Jude” on a placard around the neck of an elderly Jew in the bottom left-hand corner. Clearly, Chagall did this not to obscure the guilt of the German regime but to place its Russian counterpart as equivalent, and so raise the totalitarian horror of that period – and its specific anti-Semitic focus - to a more universal plane.

One of the most important of these later paintings, Wall Clock with Blue Wing – painted in 1949, in the period of Stalin’s round-up of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee following the murder of Mikhoels – was shown in the exhibition at Tate Liverpool, but with no indication as to its range of resonance. Dark sky, deserted snowy streets, a bouquet of flowers abandoned on the snow, Jackie Wullschlager describes it as “a painting that suggests emotional collapse. Chagall was finishing the work just as news came from Russia of the disappearance of Jewish intellectuals including his friend Feffer as well as Perets Markish…”.

“For Chagall it was the last disillusionment about Soviet Russia….Doubts and grief about Russia, therefore, fed into Wall Clock with Blue Wing.” (pp.449-50)

No clue as to the context of this major work was provided by the Tate.

In the same way, one is free to read Chagall’s major painting, The Fall of Icarus – painted in 1975 when he was nearly 90, with Icarus poised to tumble to earth among the houses of old Vitebsk – as a parable on the over-reaching hubris of young Jews like himself and his perished friends who had embraced the ethos of the revolution.

It is ironic that in a large exhibition in 2010 with the very questionable title, Picasso: Peace and Freedom, Tate Liverpool similarly provided no adequate information about Stalin’s anti-Jewish pogrom when it showed Picasso’s late work, with his celebratory image for the dictator’s birthday in November 1949, inscribed Staline, a ta Sante (“Your health, Stalin!”), as well as Picasso’s romanticised portrait produced for the front page of the French Communist newspaper, Les Lettres Francaises, within days of the dictator’s death in 1953.

During “these nasty, murderous (non-Jewish) times”, as Chagall described this period in a letter in July 1950 to Abraham Sutzkever, a Yiddish-speaking friend and poet then living in Tel Aviv, it was at a lunch near Antibes on France’s Mediterranean coast that his break with Picasso took place, an event defined along the line of fracture between Stalin and the Jews.

As Wullschlager reports, Picasso asked Chagall why he never went back to Russia.

“Characteristically, he touched the rawest nerve: at just this time Michel Gordey [at the time, Ida Chagall’s husband] had gone on a journalistic assignment to Moscow, meeting Mrs Feffer and seeking news of Feffer, whom Chagall now knew to be alive but imprisoned.…

“But to Picasso he only flashed a broad smile and suggested that as a member of the Communist Party, he should go first, for ‘I hear you are greatly beloved in Russia, but not your painting.’”

The first-hand account of the interchange cited here by Wullschlager comes from Francoise Gilot, Picasso’s then lover, who was present at the lunch. Following Chagall’s response about the painter’s Communist Party membership, Gilot continues: “Pablo got nasty and said, ‘With you I suppose it’s a question of business. There’s no money to be made there.’”

Business…money…Jew.

That “finished the friendship, right there,” writes Wullschlager (pp.455-56) A fuller account from Francoise Gilot appears in Monica Bohm-Duchen’s Chagall. (p.286)

Chagall had long since in his work replaced his image of Lenin doing a handstand (in his 1937 painting, Revolution) with a crucified Jesus the Jew: probably the most definitive image of Chagall’s late paintings, appearing in numerous works, including his epoch-defining War.

With its shocked and agonised white ram as witness to the cruelty inflicted on humans by humans, Chagall’s War is a painting to consider alongside the wounded horse of Picasso’s Guernica. There is a full-scale embroidered reproduction of Guernica at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and it would have been illuminating to see these works together.

However it was beyond the capacity of the Tate even to suggest this, even though the significance of a modernist (and Jewish) artist restoring the crucifixion to its central place in the iconography of Western culture as a means of conceptualising its 20th century horrors is strongly argued by Jonathan Wilson in his brief monograph, Marc Chagall (Schocken/Jewish Encounters, New York, 2007). While primary attention is given to the Holocaust, Wilson gives inadequate attention to Chagall’s re-evaluation as a painter of the Soviet experience of his native Russia.

It is not out of place to note that the Russian contributor to the Tate catalogue, Ekaterina L. Selezneva – a former deputy director of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and author of an essay titled “Chagall’s murals for the Yiddish Chamber Theatre in Moscow”– is listed on its back cover as Head of the Department of International Cooperation of the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation: in other words, an official of the government. It is legitimate to wonder how a contemporary Russian government official might be able to investigate the atrocities of the Russian government of 70 years ago, and how appropriate it was for the Tate to have Chagall’s heritage of pain explored for British viewers in this way.

It is difficult to imagine how Chagall might have evoked the horror in Russia, had he not been so conscribed. As he wrote concerning “the unfortunate Jews in Russia” to his friend, Kadish Luz, the Speaker of the Knesset in Jerusalem, in December 1970, “I have to – alas – restrain myself in many ways” so as not to harm his sisters in Russia, and their families. “I have ‘restrained’ myself like this for 50 years. What can you do?”

As Arno Lustiger, a Polish Jewish survivor of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, notes in his study, Stalin and the Jews. The Red Book: The Tragedy of the Soviet Jews and the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (Enigma Books, New York, 2003), Mikhoels’s daughter Natalia asked Chagall to create illustrations for her biography of her father, after she and her sister Nina were permitted to emigrate to Israel in 1972. Chagall “rejected her request with the explanation that he did not like to support projects critical of the USSR.” (p.329) It is not hard to guess his interior reasoning. In her biography, translated into French as Mon Pere, Salomon Mikhoels: Souvenirs sur sa Vie et sa Mort (Montricher, Switzerland, 1990, written in Russian and first published in Israel), Natalia Vovsi-Mikhoels describes her father and Chagall as having a “mutual understanding worthy of telepathy”. (p.28)

Just as in the music of his contemporary, Dmitri Shostakovich, Chagall’s post-war Russian trauma was constrained to wear a mask and be oblique.

Yet it is possible to consider the spooky, white-faced musicians in Chagall’s Saltimbanques in the Night (from 1957, and item 89 in the catalogue) as ghosts of the Moscow Yiddish Theatre, murdered by Stalin, and with it the Renaissance of Eastern European Yiddish culture - the anguished spirits of Mikhoels and Zuskin, Dobrishin, Markish, Der Nister, and their colleagues. Chagall’s deeply individual imagination, with his range of symbolic meaning derived from theatre and from circus, could find tragedy in Fool’s clothing. The antics of Mikhoels could be seen in Mauve Nude (1967), the last work in the exhibition, clothed – disguised - as Harlequin,

None of this finds expression in the catalogue.

The Tate’s exclusion of the Stalin terror in its effect on Chagall, through the murder of his friends and its repression of Jews, must be accounted a severe moral failure. Given the amount of information available to the curators, this came perilously close to a form of censorship on the part of Britain’s premier state-funded art institution, with a very damaging effect for understanding of this Jewish artist’s work.

Marc Chagall, Music (1920), tempera, gouache, and opaque white on canvas. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow