Gwynne Schrire, a veteran contributor to Jewish Affairs and a long-serving member of its editorial board, is Deputy Director of the SA Jewish Board of Deputies – Cape Council. She has authored, co-written and edited over twenty books on aspects of South African Jewish and Western Cape history.

Recently, I was interviewed for a seven-part television series, named Legends and Legacy: A History of South African Jews, being prepared with the assistance of the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies & Research at the University of Cape Town and Professors Milton Shain and Richard Mendelsohn. The question was asked, “Did the Jewish Board of Deputies sit on the fence during apartheid?” Although this subject has been rigorously analysed by, amongst others, Gideon Shimoni and Atalia ben Meir (see ‘References’ below), I was looking at it from a Cape perspective. My answer to that question was “Yes …but”.

The ‘but’ is important.

It is true that in the first decades after the National Party (NP) came into office and commenced introducing and enforcing rigid racist laws designed to separate the society based not on merit but on melanin, the Board consistently followed a policy of collective non-involvement. It was only from the mid-1970s, with increasing international and local condemnation of apartheid, accompanied by increased state awareness that change was necessary, that it became tenable for the Board to climb off the fence without risking the security of the Jewish community. It was not until 1985, however, that the National Board explicitly condemned apartheid.

According to John Simon (Cape Board chairman 1975-1977), the Cape was always in the vanguard of efforts to propel the SAJBD in a more liberal direction. Solly Kessler (Cape Chairman 1981-1983) wrote that in regard to the apartheid regime and its policies of racial discrimination, the SAJBD’s records as well as the recollections of former members of the National councils confirm the distinctly more liberal stance consistently adopted by the Board’s Cape representatives as compared to the attitude evinced by other provincial delegates. Indeed, from as early as the late 1950s, Cape delegates brought resolutions (routinely voted down) to National conferences calling on the SAJBD to denounce apartheid.

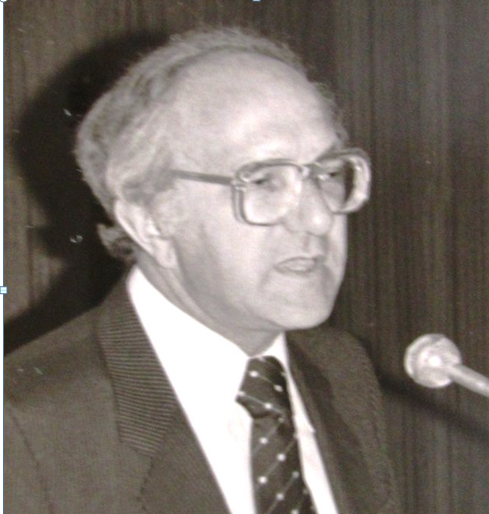

John Simon, SAJBD Cape Chairman 1975-1977

To understand the reasons for the National Board’s decision to sit on the fence, one needs to look at the matter not with the eyes of the 21st Century, but within the context of the time in which those decisions were made.

The SAJBD was founded to safeguard the civil and religious rights of South African Jewry. It would hardly have helped that community had it become just another of the many organisations banned by the apartheid government. Would this have happened? Who knows, but it was certainly possible.

To judge the Board’s policies of neutrality, it must be remembered that when the NP came into power in 1948, its unexpected victory (by five seats) was not welcomed by Jews, and for good reason. Parliament sits in Cape Town and the Cape Board since its inception in 1904, kept an eye on legislation affecting Jewish civil and religious rights. During the 1930s, the Board had been spent much time countering antisemitism both within Parliament and outside. Morris Alexander, a founder and first chairman of the Cape Council, as a Member of Parliament tried to counter antisemitic rhetoric in the House and any threats of anti-Jewish legislation. There were plenty of reasons for the Jewish community to distrust the new government. In 1933 a Nazi movement, the South African Gentile National Socialist Movement (better known as the Greyshirts) was founded by Louis Weichardt just around the corner from Parliament. It held inflammatory anti-Jewish meetings across the land, distributing leaflets saying that the Jews were Asiatics and should be excluded as a menace to the country. In 1938, the pro-German paramilitary Ossewabrandwag (OB) based on national-socialism was established and in 1940 the pro-Nazi New Order was founded by Oswald Pirow, who had met Hitler and Mussolini and wanted to establish a Nazi dictatorship. To counter this antisemitic onslaught, Alexander resigned his chairmanship to conduct a fact- finding and fundraising tour of the country communities and the Board sponsored counter- propaganda in the form of brochures and publication (such as the book on antisemitism by Afrikaans MP Abraham Jonker, Israel die Sondebok - the English version was called The Scapegoat of History).

Then came the war, the Holocaust and for local Jews the discovery that their relatives in Lithuania and Latvia had vanished, swallowed up in pits in the forest or up the chimneys of Auschwitz. The Board’s Relatives Information Service was faced with the task of trying to locate non-existent survivors for traumatised families.

Then the NP came into power. The ban on the OB was lifted and its members, as well as those of the Greyshirts and the New Order were welcomed into the ruling party. Now many of those antisemites were sitting in Parliament. Like the new Prime Minister Dr DF Malan, who in the 1930s had wanted to restrict Jewish immigration and limit their ability to practice certain trades and professions. Like future Prime Minister Dr H F Verwoerd, who had tried to stop German-Jewish immigration. Like another future Prime Minister and former OB General B J Vorster. Like future State President Nico Diederichs, who had studied Nazi methods in Germany and was regarded as “a Nazi through and through”. Like Greyshirts founder Louis Weichardt, who became a Senator. Like Oswald Pirow, who received a Cabinet appointment. (A Street in central Cape Town was named after him. In the new South Africa, the Cape Board successfully lobbied the City Council to change the name - it is now called after Chris Barnard). Like OB member Hendrik van den Bergh, who became head of the Bureau of State Security. Like Johannes von Strauss von Moltke, who the Board had successfully prosecuted for his part in forging a document based on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and attributing its authorship to a Port Elizabeth rabbi, and who was now a National Party MP for one of the South West African constituencies.

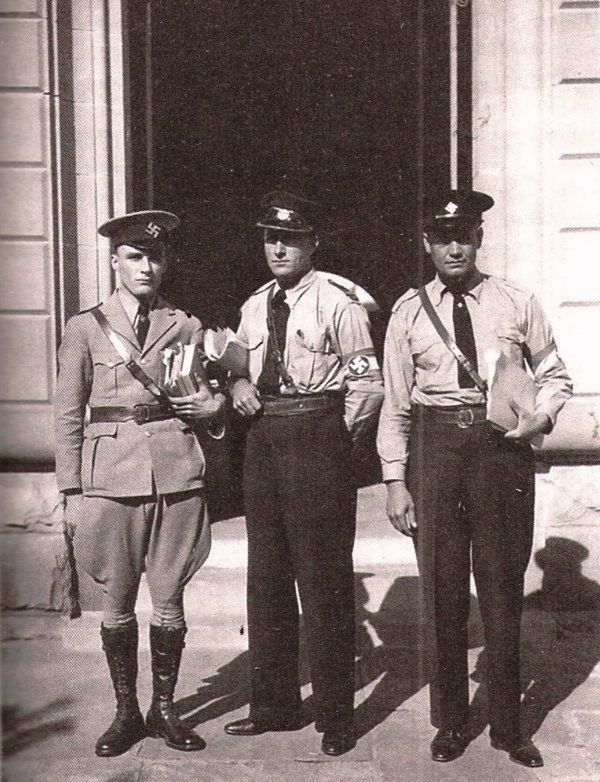

Greyshirt leaders accused of antisemitic defamation outside the court, Grahamstown, 1934

If SA Jewry had felt threatened by the antisemitism of the 1930s and 40s, this new government hardly made them feel any more secure. Nor would the raft of rapidly-passed racist apartheid laws reminiscent of Nazi legislation and Tsarist discrimination have reassured them. Was it realistic under the circumstances to expect the Jewish community to openly attack the government’s policies? It is easy, 25 years into a new and free South Africa, to condemn the Board’s stance; we forget how dangerous any opposition was under NP rule. Under the circumstances, it would have been foolish for the Board to attack that government on its racist policies.

In any case, criticism of apartheid was progressively circumscribed over time, beginning with the 1950 Suppression of Communism Act. Restrictions were further tightened in 1962 by the General Law Amendments Act and subsequent legislation. People were arrested, tortured, banned, placed under house arrest and jailed without trial, at first for 90 days, then 120, then 180. I myself had a banned boyfriend who had spent some time in solitary confinement. He could not visit me legally because I lived in a different part of Cape Town. I worked at a welfare organisation. One of its case secretaries was banned. She could not join the other social workers at tea, as she could not meet with more than one person at a time. Both subsequently left South Africa.

It is necessary to stress once more, that when criticising the Board from the safety of the new South Africa, one has to realise the conditions under which South Africans were living prior to the transition to democracy. Basic democratic freedoms - of the press, opinion and belief and association – were severely restricted. Newspapers were banned, as were organisations, and individuals were arbitrarily jailed. It was a country where a TIME Magazine issue containing a photo of a black man dancing with a white woman could not be distributed until the offending picture had been scissored from every copy. Even the children’s book about a horse called Black Beauty was banned. Once Dr Aubrey Zabow (Cape Board chairman, 1977-1979) was raided in the early hours of the morning because his banned cousin, writer Ronald Segal, had sent him a banned book he had written. Among the books the security branch confiscated was The Inner Revolution. Dr Zabow was a psychiatrist and that book dealt with advances in knowledge of brain chemistry. The Zabows went on aliyah after struggling to get passports - a Jewish MP assisted in getting them returned.

These laws controlled virtually every aspect of life, from who one could marry, to with whom one could socialise, where one could live, where one’s children could go to school, and what work one could do. There were police informers and special branch policemen whose work entailed looking through keyholes and bedroom windows to see who was sleeping with whom. It was a country of White suburbs, Coloured suburbs, Indian suburbs and Black suburbs - entering a Black suburb without a permit was illegal. Race groups were segregated into separate elevators, separate post offices, separate park benches, separate beaches, separate cinemas, separate parking areas for drive-in cinemas (with the separated audience sitting in separate cars but watching the same film), separate pedestrian bridges, separate schools, separate hospitals, separate churches, separate graveyards, separate everything. It was a sports-mad country which cancelled the visit of a touring English cricket team (1968) because it included a Coloured cricketer, Basil d’Oliviera; where education was on Christian National Principles and where the constitution of the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education had a modified Conscience clause to ensure that no Non-Christian could be appointed to a teaching, research or administrative position. (Their conscience allowed them to accept donations from Non-Christians.) Reluctant to expose their children to Christian National Education, most Jewish parents in Cape Town sent their children to the Herzlia schools.

hen my father gave the housekeeper a lift to the station, he took me with him so that he would not be arrested on suspicion of breaking the Immorality Act. An acquaintance’s husband, a lawyer, was arrested under that Act. The woman was imprisoned, the man committed suicide and his widow left the country. Actions had dangerous consequences in apartheid South Africa. This article is only looking at how Apartheid impacted on the proportionally tiny Jewish community vis-à-vis the actions of the SAJBD, not on the horrific and all pervasive impact of those discriminatory laws on the large majority of the society not classified as ‘white’.

The Board’s main task is to protect Jewish civil rights; as such, it is a defensive body, not an activist one. Its constitution restricted it to matters affecting the Jewish community. Would it have been in the community’s interest for the Board to condemn the policies of a government on which it relied for its protection, that contained many antisemites and which had the will and power to punish dissenters? As a body that protected a minority community, self-protection came first. Historically, Jewish communities living as a minority in their societies had learnt that sticking their necks out on behalf of other groups being persecuted by the rulers was not a good survival strategy and might lead to those heads being chopped off.

Ronald Segal, whose father Leon had chaired the Cape Board in the years 1942-46, thought that the community should have criticised government openly, even if it was punished for doing so. He believed that in as much as whole communities had been martyred in the Middle Ages, so should the Board have taken the risk even if it meant communal sacrifice.

However, the Board and indeed the community thought otherwise. Atalia ben Meir has pointed out that although the Board never undertook a scientific survey of opinions, it had no doubt that the community would condemn it if it criticised the government’s apartheid policies. Some brave people were prepared to be martyrs, and we honour them for that, but most were not prepared to be sacrificed. Not even Ronald Segal, as it turned out. His elder brother Cyril once told me how he had smuggled him over the Rhodesian border in the boot of his car after Ronnie’s banning in 1959.

The NP had a few Jewish supporters. One was Joseph Nossel from Wynberg, who approached the Cape Board to help him start a Jewish wing of the NP. The Board responded that it had no connection, official or unofficial, with Nossel, that although Jews had an unquestioned right of complete freedom of political action, that right did not extend to anyone wanting to organise a Jewish wing of any political party. The Board thereupon issued a statement stating that Jews, as individuals, could do as they wished, but the Board itself would not take sides on specific government policies unless the rights and dignity of Jews were directly threatened. It repeated the same answer when the English-speaking John X Merriman branch of the Cape NP asked for Board support.

The Board consistently stuck to this policy and repeated it at subsequent conferences. That policy of political non-involvement prevented it from promoting pro-apartheid groups, but also from supporting anti-apartheid statements, and that lead to much later criticism and controversy. There were those who said that the Board had no business whatsoever making statements on controversial issues not directly affecting SA Jewry. The Jews were no longer considered Asiatics but as whites, in a white society. As such, they were privileged and did not want to lose those privileges.

Others felt equally deeply that when it came to matters of racial prejudice and denial of human rights the Board, as a Jewish organisation, had an obligation to speak out. Benjamin Pogrund, formerly Deputy Editor of the Rand Daily Mail, called the Board timid, pallid and nervous. Wits University’s Prof Julius Lewin, despite having previously written that Jews in SA felt nervous and were frightened of the “ruling race”, asked why the Board as the community’s representative was silent when other communities were enduring such injustice - Jews who had suffered so much should not keep quiet, he insisted. The Student Jewish Association at the University of Cape Town was harshly critical of the Board’s stance, particularly in its newspaper Strike. However, students did not have dependent families, careers and businesses that might be put at risk.

International bodies criticised the Board, but then they were not in a position where speaking out could endanger their communities. Maurice Porter, chairman of the Board’s Public Relations committee, told the World Jewish Congress in 1964 that it would be suicidal to throw the community into the political arena.

The Board maintained that a collective view did not exist, and that its role was to ensure Jewish communal survival, not communal martyrdom. In the early decades of apartheid rule there was broad support for this approach from the community. Both the Board and the community believed that their community would be jeopardised if they opposed the government and its racist policies.

This view was also held by the religious leadership, few of whom had the courage to speak out against policies that went directly against Jewish values. The handful that did, a number of who like Rabbis ES Rabinowitz, Steinhorn, Rosen, Franklin and Sherman, served congregations in Cape Town often faced hostility from their congregations or the prospect of having their visas revoked. Rabbis could also feel fear when living in what Prime Minister Vorster had called “the happiest police state in the world”.

Cape Chairman Max Malamet (1957-1959) pointed out that the Board had to weigh the pros and cons of every suggested action very carefully, since their freedom of action was limited by prudential consideration. He believed that whites would have to reconsider their attitudes to non-whites and hoped that even the most dogmatic and militant of their politician would have common sense. This was in 1957. It would be another thirty years before common sense came to the fore.

The Board did struggle with the demands of being true to Jewish ethics and morals and issued bland statements about dignity and freedom and justice for all, from which all political criticism was removed. The National government was not fooled and queried Jewish loyalty. Why, after all, did Jews comprise over half of the 23 whites in the Treason Trial of the 1950s, and all five of the white people arrested at Rivonia in 1963? Die Burger pointed out that as far as was known, not a single Jew who supported the NP was in any responsible position on the Board. There was an outcry both within the Jewish community and from the opposition in 1968 when the Minister of Police blamed the Jewish community for not preventing its youth from taking part in protests at UCT. This time the Board responded with firmness that no Jewish body would interfere with its students’ political freedom and it was wrong to single out Jews. On this occasion, the NP made an effort to appease the Board.

From the late 1970s, opinions were beginning to shift. The government started to take tentative steps to ease its restrictive policies and it became safer to speak out. Bodies like the End Conscription Campaign and Jews for Justice developed and began openly to challenge apartheid.

At a banquet to honour Prime Minister Vorster following his visit to Israel in 1977, Board president David Mann first uttered a parev comment, certainly not a condemnation, but definitely a statement referring to the previously forbidden topic of government policies: “There is a new sense of urgency abroad in our land, a realisation that we must move away as quickly and effectively as is practicable from discrimination based on race or colour.”

Looking at the Board’s fence-sitting policies, we should not look at the Jewish community in isolation; similar policies were practiced by other minority groups for similar reasons of group survival. The Greek, Portuguese, or Italian communities, although not having the same history of persecution, were also hardly outspoken in their criticism, and certainly produced far fewer anti-apartheid activists.

The Muslim Judicial Council (MJC) likewise came in for much criticism from its youth for its silence. Between 1961 and 1964, the MJC issued just five statements condemning acts of apartheid and held only one public meeting. Faried Esack criticised the MJC in terms very similar to the criticism issued by Jewish students, saying that it could and should have done more. The contribution of the religious leadership, he told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), “despite whatever nice words are used...was essentially one of betrayal. There was a denial of space for all those who opposed apartheid and who were part of the anti-apartheid struggle”.

But the MJC, like the Board, was trying to protect its community with the additional disadvantages of being classified as non-white and as followers of what was called a “false religion” and its offices had been raided by the Security Police. Like the Board, it found its voice only later when it became safer to speak out. In 1976, after the Soweto Uprising, it issued a strong letter protesting the police brutality against children and young people and in 1985 the MJC participated in a march to demand freedom for Mandela.

Returning to the Cape Board, there were frequent differences of opinion between the Cape and National Board in Johannesburg. Cape Town has always been more liberal, more verlig, than its counterparts further north. This might have been its inheritance from having belonged to a former British colony, not to a former Independent Boer state with more rigid ideas about colour and baaskap. It might have been because it was acculturated to English rather than Afrikaans social and religious mores. Solly Kessler thought it was understandable that Cape Jewry would have a more progressive attitude regarding the apartheid policies (as could be seen in the line taken by the Cape committee) because the social distance between the Cape Jewish community and members of the non-white communities was far less than elsewhere.

Solly Kessler, SAJBD Cape Chairman 1981-1983

This difference between the verligte Cape and the verkrampte Transvaal was not only found amongst Jews. The Transvaal’s Jamiatul Ulama was condemned by Imam Solomon at the TRC for its conservative, sometimes even reactionary stance: “They obstinately refused to be moved from their record of silence on any political issues which would appear to be anti-state… Pressure by the Muslim Youth Movement persuaded the Natal Jamiat to speak out against the election, but the Transvaal Jamiat was consistent in its silence”.

There was long simmering disagreement between the Cape and National Boards on the latter’s reluctance to condemn. Ben-Meir has recognised that in the latter half of the 1970s, the Cape Council took the lead in totally abandoning the Board's conservative policy towards the political arena, while the National Board was slower to move to active involvement in SA's political problems.

In 1977 National President Mann attended a Cape Council meeting to defuse the differences, without success. Cape Chairman John Simon told him that the Board should be in the vanguard of political change. Archie Shandling (Cape Chairman 1980-1981) insisted that in view of the Jewish people's long experience of religious and racial discrimination it was a dereliction of responsibility for their community to draw a distinction between moral and political issues. The Cape Council needed to comment on crucial issues in the light of Jewish ethics. It should no longer evade the issue.

Jack Aaron said the Board should stand up and be counted as it was contrary to Jewish ethics to allow discriminatory legislation to exist without voicing condemnation. The preservation of Jewish identity, he argued, was contingent upon displaying such ethical courage. They should oppose all discriminatory practices.

Simon suggested that the Board move beyond the original idea of defending Jewish rights and engage in speaking up on any issue connected to individual freedom, which could ultimately affect the community. However, even the Cape Council felt this was going too far. Zabow reminded him that the Board needed to refrain from making political statements unless this was on a Jewish aspect, as their community was only a minority and furthermore Jews belonged to all political parties.

The only response Mann could give was to repeat the old chestnut that the Board only had a duty to speak out on moral matters if there were a Jewish content.

The following year relations between the Cape Board and the Johannesburg Executive remained strained. Chairman Aubrey Zabow argued that that the time had come for the voice of the Jewish community to be heard on significant moral issues. Views were changing in South Africa - even cabinet ministers (!) were realizing that the old system with its unjust discriminatory practices could no longer persist. The effort was being made everywhere to bring these practices to an end and it was becoming increasingly clear within the Jewish community that it was necessary to relate to the non-white sections as fellow citizens not only as a matter of morality, but of recognising the changing situation in South Africa. The Jewish community should be publicly seen to stand by its principles.

The Cape Board knew that the Johannesburg executive would never approve of their stance. They regretted the divergence of opinion but stood by their conviction that the Board should be committed to the full participation of everybody living in South Africa in every aspect of life.

Simon and Solly Kessler agreed that the National Conference would be unlikely to accept the Cape’s statement. Shandling then suggested that even if it meant taking an unpopular stand that would risk estranging the National Board, and being forced to accept an unsatisfactory compromise resolution, the Cape Board should produce a minority statement.

Dr Frank Bradlow (Honorary life vice president of the Cape Council) realised that these Cape decisions would be perceived by Johannesburg as being contentious. He regretted that the Cape and Johannesburg had different opinion, but also agreed that the Cape needed to express its commitment to full participation by everybody who lived in South Africa.

In 1979, the Cape again clashed with National when it went ahead and issued a statement that silence was not an option when government threatened human rights and started to act on that. In the 1980s, it condemned detentions without trial, the detention of children and the actions of police during peaceful gatherings. It further called on government to allow Coloured learners to write supplementary matric exams when rioting had prevented them from doing so.

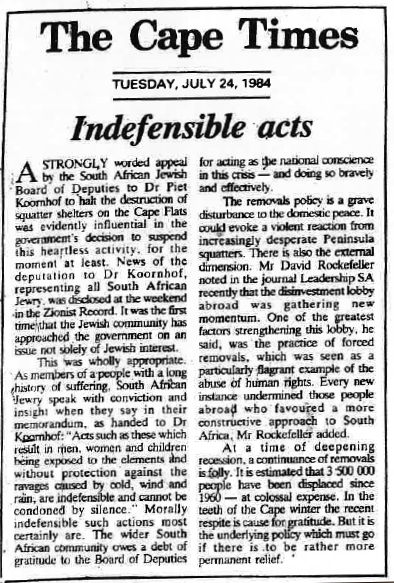

In 1981, the Cape Argus praised the Board for joining the Council of Churches in condemning the police for invading the Langa bachelor quarters. In 1984, the Cape Council led a delegation to Dr Piet Koornhof asking him to stop the destruction of shacks in Khayelitsha and the Cape Times in a leader article commented that the wider community owed a debt of gratitude to the Board for acting as the national conscience.

Finally, in 1983, the National Congress took hesitant steps to climb off the fence and called upon all South Africans, particularly members of the Jewish community, to co-operate in securing “the immediate improvement and ultimate removal of all unjust discriminatory laws and practices based on race, creed or colour”. Then, in June 1985, the Board - for the first time - used the word “Apartheid” in a resolution explicitly stating that the Board rejected it! In that resolution, it recorded its support and commitment to justice, equal opportunity and the removal of all provisions in the laws of South Africa, which discriminated on grounds of colour and race.

Did the Board act as a national conscience as the Cape Times had so generously claimed? No it did not, and nor did most of the rabbis. Mervyn Smith (Cape Chairman 1983-7 and National Chairman 1991-5) believed that both failed the struggle. He felt strongly that there was a general failure of the community leadership although “there were nonetheless those Jewish leaders of conscience, small in number, who year in and year out attempted to force a moral public stance upon the leadership.”

Smith added that he was proud to say that they largely came from the Cape Council. It is hoped that this article will go some way to providing recognition to the attempts by the Cape leaders to push the National Board off the fence earlier.

Mervyn Smith, SAJBD Cape Chairman 1983-1987 & National Chairman 1991-1995

Would it have made a difference to the government’s apartheid policies had the Board taken a moral stance sooner? No, as a small insignificant minority, the community’s condemnation would have had minimal effect, amounting as it did to barely a drop in the pond that made up the mind-set of the bigots ruling the country. Would the government have punished the community if its representatives had spoken out? It is difficult to say. Certainly it did so in 1961 by forbidding the transfer of funds collected for Israeli causes when Israel voted against South Africa in the United Nations, but equally, there was no retaliation when the Board stood up to it seven years later over the rights of Jewish students to protest.

Times change and we change with them. By the 1980s, common sense was at last beginning to prevail. With the recognition that change was inevitable, criticism became more acceptable and it became less dangerous for both the Jewish and the Muslim communities to speak out in language that was not so guarded and diplomatic.

Were Jewish fears unreasonable under the circumstances? With the community’s centuries of experiences of being persecuted and scapegoated, it can certainly be argued that the Board, by its silence, was protecting the community as best as it could. With the background of antisemitism during the 1930s and 1940s, these fears were surely reasonable. The Board at the end of the day was simply behaving in the way that Jewish leadership had learnt over the centuries to be the best way to safeguard the security of those it represented.

References

Ben-Meir, Atalia, The South African Jewish Board of Deputies and Politics, 1930-1978 (PhD Thesis, University of Natal, 1995)

Robins, Gwynne: South African Jewish Board of Deputies (Cape Council) 1904-2004, 5664-5764: A Century of Communal Challenges, 2004

Shimoni, Gideon: Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 2003