David Saks is Associate Director of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies and editor of Jewish Affairs. This article is adapted from his presentation at Limmud in Johannesburg on 18 August 2019.

Even before South Africa’s transition from white minority rule to multiracial democracy in April 1994, a veritable flurry of discussion had gotten underway within Jewish circles concerning the community’s political behaviour under apartheid. The topic itself was not a new one. Over the preceding two decades, it had surfaced with increasing frequency at the national conferences of both the SA Jewish Board of Deputies (SAJBD) and the SA Zionist Federation (SAZF). University students and members of the leftish Habonim Zionist youth movement in particular had been vociferous in calling for the representative leadership to take a decisive moral stand on the issue. From the beginning of the 1990s, it became one of the dominating topics of the day. Symposiums were convened, many articles and even books written, exhibitions mounted[i] and conference session devoted to the topic. The earnest, frequently acrimonious debate was still being periodically revived well into the next century.

Sometimes, one could help wondering whether the Jewish community was not making altogether too much of the matter. After all, the political behaviour of a small minority within the white population can hardly be said to have been one of the most pressing issues of the liberation struggle. Yet a great many community members felt otherwise, and with South African democracy having passed its first quarter-century only last year, it may be an appropriate time to re-examine the question.

Why has the subject attracted such enduring interest? Part of the answer certainly is the startlingly disproportionate number of Jewish community members who played a role in the anti-apartheid movement – in many cases a very significant role. From a purely academic point of view, this begs the question. There does also appear to have been a dual motivation, characterized by American Jewish academic Todd Pitock as a combination of “self-congratulation and self-flagellation”.[ii] Jews, it seemed, wished to boast about their apartheid-era record while simultaneously apologising for it.

Why ‘self-flagellation’? This was due to the reality that at the collective level, the Jewish community and its official leadership had been largely passive during the era of white minority rule. Admittedly the SAJBD, the community’s official spokesbody, had eventually adopted an explicitly anti-apartheid position,[iii] but this occurred rather late in the day, when even sections of the Nationalist government were making similar noises. Categorically denouncing apartheid and all it stood for would have meant a great deal had it occurred in the mid-1960s; that it took place only from the early 1980s onwards greatly lessened its impact, although it would be wrong to conclude that it was entirely without value.

SAJBD President Gerald Leissner and Chairman Mervyn Smith (pictured here with ANC President Nelson Mandela, SAJBD National Congress, 1993) were instrumental in the Board’s taking a decisive stance against apartheid during the 1980s.

The ‘self-congratulation’ aspect is also easy to explain since none of the country’s other ethnic white communities came close to producing so high a proportion of individuals who opposed apartheid than the Jewish community. Even a short-list of Jewish anti-apartheid activists would include:

- Parliamentarians Helen Suzman, Harry Schwarz, Sam Kahn, Leo Lovell and Brian Bunting.

- Lawyers (who defended activists in major political trials from the 1940s onwards) Isie Maisels, Arthur Chaskalson, Sidney Kentridge, Joel Joffe, Shulamith Muller, Denis Kuny, Jules Browde and a host of other lesser known but still significant figures.

- Trade unionists Ray Alexander, Benny Weinbren, Solly Sachs and Leon Levy

- Political activists Lionel and Hilda Bernstein, Joe Slovo and Ruth First, Arthur Goldreich, Harold Wolpe, Ben Turok, Dennis Goldberg, Wolfie Kodesh, Paul Trewhela and, later, the Coleman family, conscientious objector David Bruce, Pauline Podbrey and Raymond Suttner.

One really could go on and on in this vein: Journalists, academics, creative artists…. members of the tribe seem to pop up everywhere. How does one explain the fact that two-thirds of the 21 white activists in the Treason Trial were of Jewish origin? Likewise, how does one account for every one of the white activists arrested in the Rivonia Raid and its immediate aftermath being Jewish? Without the Jewish activists, there probably wouldn’t have been a Freedom Charter, and perhaps not even an Umkhonto we Sizwe. Later, Jews played a critical part in the establishment of such organisations as the Detainees’ Parents Support Committee, the Legal Resources Centre and the End Conscription Campaign.

For SA Jewry, the awkward transition from a society based on entrenched white privilege to non-racial democracy was undoubtedly eased to some extent by the fact that individual Jews had done so much to bring about the new order. Certainly, it helped the Jewish leadership to punch above its weight in terms of accessing government and having input into public policy.

Jews typically relish compiling lists of other Jews who have made it big in some way, from Nobel Prize winners through to film stars, musicians, scientists and inventors and in many other fields. But doing so with anti-apartheid activists is problematical. For one thing most Jewish activists on the left of the spectrum had with rare exceptions never identified as Jews in any meaningful way. Their attitude is summed up by Ray Alexander saying that she did not see herself as Jewish but as “Internationalist”, or put another way, a citizen of the world.[iv] My own view is that so many Jews were attracted to Communism in part because it offered them an ideological escape route through which they could discard their inherited Jewish baggage and reinvent themselves simply as people no different from any others. Ironically, that was part of the attraction of modern political Zionism for many Jews, particularly those living as a persecuted minority in Eastern Europe.

Jewish Struggle veterans, especially those who had fought apartheid outside the legal parameters allowed by the regime, were not going to allow the mainstream to community to claim credit for the risks they had taken and the sacrifices they had made now that it was safe to do so. They were – not without justification - scornful over how the community now apparently wished to use them as a front to sanitize its collective behaviour when at the time it had by and large been happy to look the other way – or even explicitly distance themselves from people with whom they were now opportunistically trying to ingratiate themselves.

As is almost always the case with sweeping indictments of this nature, the issues are not so simple, and on at least two levels this one is open to challenge.

One rejoinder is that the Jewish leaders who had failed to support Jewish activists at the time and those entrusted with leading the community into the democratic era were not the same people. The latter were from a completely different generation, with many having not even been alive when the likes of Joe Slovo, Esther Barsel, Eli and Violet Weinberg and Denis Goldberg were being imprisoned, detained without trial or banned. During the 1980s, the progressive faction within the SAJBD had finally managed come out on top, and it was they who constituted the leadership of the organisation after 1994. Was it really reasonable, or even fair to accuse them of hypocrisy and opportunism, let alone subsequent generations?

Eli Weinberg in the Johannesburg Fort – sketch by fellow prisoner Paul Trewhela, 26 October 1964

The Jewish establishment can also point out that that Jewish activists - certainly the more radical ones - in reality had turned their backs on all things Jewish well before the rest of the community turned its collective back on them. They had denounced Zionism, scorned Judaism and eschewed any kind of Jewish education for their children. They did not even involve themselves in organisations specifically combating antisemitism, maintaining instead that this had to be subsumed within a broader campaign against racism in general. Worst of all, perhaps, many had actively supported some of the most virulent enemies of the Jewish people in the post-World War II era, including the Soviet Union and the pre-Oslo Palestine Liberation Organisation. What moral right did such people have – as Jews – to lecture the rest of the community on how its members should have behaved?

These are valid points, but in the final analysis one can’t help but cringe a little when reflecting on how readily, even obsequiously, the Jewish establishment rushed to embrace those whom they had previously claimed were simply Jews by birth, with no meaningful ties to the Jewish community as a whole.

Jewish anti-apartheid activists fell into two broad categories – liberals and leftists.[v] Liberals generally campaigned against apartheid from within legally permissible parameters (such as in Parliament and in the courts). They were supportive of Zionism or at least neutral about it, and many were active in the Jewish community as well. Names like Dr Ellen Hellman, Benjamin Pogrund, Jules and Selma Browde and Harry Schwarz come to mind. Leftists, by contrast, tended to be convinced Communists who simply from an ideological point of view did not wish to identify as Jews. At most, their Jewishness was part of a loose cultural inheritance that they and their immediate forebears had brought with them from Eastern Europe and which as such could be no more than superficial. It was within the anti-apartheid left that the disproportionate nature of Jewish involvement was especially striking.[vi]

While tending to be more connected to the Jewish community, Jewish liberals have also been scathing about the leadership’s behaviour under apartheid. One is Benjamin Pogrund, who while not himself a communist as an investigative journalist regularly contravened the law in order to better expose the iniquities of the apartheid system. Accusing the Jewish leadership of “running scared”, he maintains that Jewish fears of an antisemitic backlash were exaggerated, saying: “Even with full knowledge of their antisemitic background, it was inconceivable that the Nationalists would have gone any further than perhaps, at most, curtailing money for Israel. They simply could not afford to add to their problems at home and abroad, by punitive action against the Jews”.[vii]

I tend to agree with Pogrund’s assessment, but only regarding the period from perhaps 1970 onwards. In the quarter-century immediately following the ascent to power of the National Party, it would have been palpably unreasonable and indeed unjust to demand of Jews over and above everyone else that they stick their heads above the parapet. Of all white South African groupings, Jews had a genuine excuse for remaining quiet. One has constantly to bear in mind how traumatized the community was in the aftermath of the Holocaust. The majority of its members consisted of first and second generation immigrants from Eastern Europe, whose Jewish communities had been all but annihilated. Of the remainder, many were refugees from Germany, or originally came from the island of Rhodes, whose Jewish population was likewise almost wiped out. It would have been difficult to find a single Jewish family in the country who had not lost close relatives. They were grieving for loved ones who had been murdered simply for being Jews; now they found themselves living under a regime which at the time had been explicitly antisemitic, and which included in its ranks people who had been deeply involved in pro-Nazi and antisemitic activities both before and during the war.[viii] Overwhelmingly, and surely understandably, the focus of SA Jewry at that time was on working to preserve its own safety at home and on contributing to the survival and development of the new-born State of Israel abroad.

One common argument for why Jews should be at the forefront of fighting injustice, especially when it involves discrimination on the basis of race, is that they too have historically suffered such persecution. That notion makes little sense, however. Jews should surely involve themselves in the fight because Judaism teaches that all human beings have a fundamental right to dignity and equality, regardless of race or creed.[ix] They should do so not because of their collective experience of persecution, but despite it. It is ludicrous, not to say unjust, to impose a higher standard of behaviour on Jews because of their history of oppression – in reality, the opposite should be the case. If we are honest, that is how post-colonial countries, in Africa and elsewhere, have been treated.

For three years Cape Town-born attorney Sam Kahn served as a member of the Communist Party representing one of the constituencies for black voters in parliament. There, he made a name for himself for his devastating attacks on the flood of new apartheid legislation brought in by the National Party government after 1948. According to Joe Slovo – albeit a biased source – during this time Kahn was visited by an anxious delegation of Jewish communal leaders who urged him to tone things down in view of the risk it was posing to the community. Kahn allegedly responded that if Jews were hated for being Communists, they were hated just as much for being capitalists. “I’ll make a deal with you” he supposedly told his visitors, if you give up your business activities, I’ll stop being a Communist”.[x]

It is to have a laugh at the expense of the community leadership seventy or so years later, but in reality they had legitimate concerns. The Jewish origins of so many white left-wing activists played easily into stereotypes about Jews being subversive and unpatriotic.

According to Time magazine (30 August 1963), the police raid on Liliesleaf Farm, underground headquarters of Umkhonto we Sizwe, in July 1963 “touched off ominous rumblings” against South African Jewry. It was reported that when Criminal Investigation Chief RJ van den Bergh made reference to the raid in a speech, a voice from the audience cried: “Jews!” Van den Bergh’s response was that foes of apartheid might indeed be “instruments of Jews”.

Around this time, SAJBD Secretary Jack Rich was asked by the pro-government newspaper Dagbreek why so many of the white communist plotters were Jews and what the official Board view was on the matter. In response, the Board issued the following statement:

“The facts prove abundantly that the Jewish community of South Africa is a settled, loyal and patriotic section of the population. The acts of individuals of any section are their responsibility and no section of the community can or should be asked to accept responsibility therefor. If individuals transgress the law, they render themselves liable to its penalties.

The Jewish community condemns illegality in whatever section of the population it appears.”[xi]

Again, it is easy with the benefit of hindsight to dismiss this response as mealy-mouthed and evasive. However, being brave after the danger has passed is one thing; it is another when the threat is all too real and immediate. When Rich received this enquiry, white South Africa was in a state of paranoia, bordering on frenzy, over the exposure of a supposed plot to violently overthrow the state, and the many Jews involved in the conspiracy had not gone unnoticed.

The SAJBD leadership was actually in an unenviable position. Its core mandate, on which understanding they had been elected in the first place, was to protect the community from antisemitism. Here, they were being virtually railroaded into taking sides between the apartheid establishment and the liberation movements. At that time of near hysteria over communist plots and imminent violent insurrection by the barbarous Bantu, any statement suggesting support for the latter would likely have provoked a strong antisemitic reaction.

On the other hand, adopting the former course - that is, explicitly condemning the underground liberation movements - was likewise not an option. The Board was not mandated to adopt political positions on behalf of SA Jewry as a whole. Moreover most Jews, while not as radical as Goldreich et al, would most likely have been quite strongly opposed to the Board issuing statements in their name that actually endorsed National Party policy. At election time, they overwhelmingly voted against the ‘Nats’ and until the late 1980s all Jewish Members of Parliament represented the comparatively more liberal Opposition. Under the circumstances the Board’s stance (on this occasion at least) should not be regarded as being deserving of harsh moral condemnation, especially not so many years after the fact by those who were not required to make the kind of on-the-spot choices that the leadership had to do back then.

This essay has until now largely focused on the track-record of the SAJBD, as this was the acknowledged representative spokesbody of the Jewish community. However, some comment at least is needed on the role of the religious leadership, who should after all have been freer to denounce apartheid from a purely moral and ethical point of view. Here, unfortunately, the record of the rabbinate is a decidedly unimpressive one. As always, it is possible to point to a few honourable exceptions, such as Rabbis Louis Rabinowitz, Selwyn Franklin, Abner Weiss and Ben Isaacson amongst the Orthodox and Andre Ungar[xii] and Arthur Saul Super from the Reform. Such individuals ensured that the rabbinate was not entirely passive during the apartheid years, but they were so few and far between as to reveal how very silent most of their colleagues chose to be.

A brief account of the extraordinary career of Rabbi Benzion (‘Ben’) Isaacson is of interest here, in part because it was so revealingly untypical but also because of all the apartheid-era Jewish clergy, none has a greater claim to having been a genuine ‘Struggle’ activist, even according to how the ANC-led liberation movements understood the term. He was the only rabbi both to join the left-wing Congress of Democrats and later the African National Congress when the movement was still in exile. Isaacson himself was never arrested or banned, although he was monitored by the security police and his home was raided on at least one occasion. Instead, he was regularly forced out by his own congregations. His own tempestuous personality undoubtedly played a role in this, but his typically fiery and provocative political rhetoric was also a major, perhaps decisive factor.

Ben Isaacson commenced his pulpit career as Assistant Rabbi at the Great Synagogue, serving under Chief Rabbi Louis Rabinowitz who became both his mentor and his champion. Blessed with unusual intellectual and creative gifts, charismatic and a brilliant orator, he was for a time seen by many as Rabinowitz’s natural successor. What made his position untenable was a very public confrontation with Dr Percy Yutar, then President of the United Hebrew Congregation and later to gain unhappy notoriety for the over-zealous manner in which he prosecuted Nelson Mandela and other leading activists during the Rivonia Trial. Preaching one Friday evening in the Chief Rabbi's absence, Isaacson lambasted the Jewish community for its political timidity, prompting an enraged Yutar to confront the 'young whippersnapper' for having put the Jewish community in 'disrepute'. Typically Reverend Isaacson (as he was then) did not back down, instead warning Yutar that he would "put him in the Johannesburg Hospital" if he did not let go his arm.[xiii]

The immediate upshot of the incident was that Isaacson was summarily dismissed and although soon reinstated (after Rabbi Rabinowitz gate-crashed a committee meeting and declared that unless he was, he would resign himself) it was obvious that another place would have to be found for him. He served for a time as rabbi to the Krugersdorp community, continuing to stridently denounce apartheid from the pulpit and dismaying many in his community by taking in the children of Ben Turok when the latter went underground to evade arrest. Rabbi Isaacson’s most sustained period of political activism commenced in the mid-1970s following his return to South Africa from Israel, where he had lived for some ten years. During this time, he was fired by one congregation and saw another congregation he had started eventually collapse as a direct result of his forthright, if sometimes overly strident rhetoric. He even travelled overseas to lobby for economic sanctions against the apartheid state, something strongly opposed even within the more liberally inclined sectors of the Jewish community. Unable to obtain another rabbinical position in South Africa, Rabbi Isaacson took up pulpits first in Harare and afterwards in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Shortly after his departure, the final unravelling of apartheid commenced with the unbanning of the ANC and release of remaining political prisoners in early 1990. Rabbi Isaacson returned to South Africa towards the end of the decade. Apart from a citation from the Union of Orthodox Synagogues, he has to date never received any recognition for his anti-apartheid record either within the Jewish community or from society at large.

Rabbi Ben Isaacson (left) with famed anti-apartheid cleric Reverend Beyers Naude

During the final decade of white minority rule, the representative Jewish leadership did unequivocally condemn apartheid, even if government would hardly have been trembling in their boots over the fact. It gave expression to what was very likely to have been the view of most South African Jews by that time, and it further meant that when the country began entering the new, post-apartheid era at the start of the 1990s, the leadership - by then that would have included Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris - was well-positioned to lead South African Jewry in embracing and being part of the transformation. It must always be remembered that the ability of the Jewish community to impact on events from a political point of view, given that by the 1980s it constituted no more than around 2% of the white population, was always minimal.

In July 2013 the SAJBD partnered with the Liliesleaf Trust in holding a dialogue (which this writer attended) to examine once more the question of Jewish political behaviour under apartheid. The format was a conversation between the Board’s National Vice-President Zev Krengel, Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre director Tali Nates and anti-apartheid veterans Denis Goldberg, Anne-Marie Wolpe and Albie Sachs. Krengel used the occasion to apologise to Jewish activists, not so much for not endorsing their political stance but for not assisting them on a basic humanitarian level when they were being persecuted by the apartheid state.

Goldberg’s sharp response was that he and his colleagues were not particularly interested in receiving apologies for themselves from the Jewish community. The real apology South African Jewry needed to make, he said, was to those who had actually been subjected to the injustices of apartheid and whose plight the community had essentially ignored.

Ironically, Goldberg himself arguably owed his early release following the life sentence imposed on him in the Rivonia Trial to the intervention both of the Jewish establishment and of Israel. I was present at an interview between historian Gideon Shimoni and former SAZF President Julius Weinstein, when Weinstein described in detail how he and the then Israeli Ambassador David Ariel approached President PW Botha to make the case for Goldberg’s release. Botha was reportedly much moved by the plea that Goldberg be allowed to spend his remaining years amongst his own people in the Holy Land, where he would in any case no longer pose a threat to South Africa. According to Weinstein, he exclaimed with tears in his eyes, “This man will be released”. And so he was, the first of the eight activists sentenced to life imprisonment to be set free.

Apart from Goldberg, there are other known cases of the SAZF and Israel successfully intervening behind the scenes on behalf of certain detained Jewish activists. Such quiet interventions were no doubt rare, but they also need to be remembered, particularly as neither Israel nor the Jewish leadership had anything to gain from them – indeed, they had quite a lot to lose in the event of it ever getting out.

Nevertheless, I think that what Goldberg said was essentially correct: At a collective level, the organised Jewish community could and should have made a much greater effort to at least help ease the plight of apartheid’s victims. This could have been done without taking any formal political stand. With so many top lawyers serving on its councils, for example, the Board could have rendered meaningful assistance to the Legal Resources Centre and other legal aid organisations then operating. It might have worked with the various women’s organisations that were affiliated to it to encourage volunteering for the Black Sash – or even establish on a more modern level a Jewish equivalent of the Black Sash. (That being said, I would stress that the Union of Jewish Women and United Sisterhood had a distinctly better record than most communal organisations when it came to both speaking out against apartheid and, more importantly, taking whatever practical steps they could to alleviate its impact).

Speaking at the SAJBD’s national conference in 1985, Arthur Chaskalson – founding director of the Legal Resources Centre and of course part of the defence team during the Rivonia Trial – summed up what he believed the Board’s role under apartheid should be. He said that although Jews as a minority had no power to affect real change, in terms of their ethical and moral values, they had a responsibility to do whatever they could in that regard. Here, the SAJBD could play a role through informing, educating and influencing individual Jews, who ultimately had to make their own choice".[xiv]

This, ultimately, is where I believe South African Jewry – in the words of the Board’s then National President Mervyn Smith – “failed the Struggle”.[xv] It could have been worse – there could have been a great deal more overt support for the regime from the Jewish community than there was. It was only in 1977 that a Jewish candidate ran for election on a National Party ticket, for example, while voting districts with a large Jewish presence consistently supported Opposition candidates. Critics of SA Jewry regularly trot out the example of Percy Yutar as evidence of Jewish collaboration, but the reality is that there were very few Percy Yutars while those on the other side – in the field of law alone - were strikingly numerous. But that was not enough at the end of the day. Great injustices were being committed under their noses, and it was only very late in the day that Jews, on a collective level, began to rise to the moral challenge that this posed. I don’t believe that this is a cause for endless breast-beating and self-flagellation, but it was undoubtedly a lost opportunity.

- See 'Readers' Comments' after Endnotes

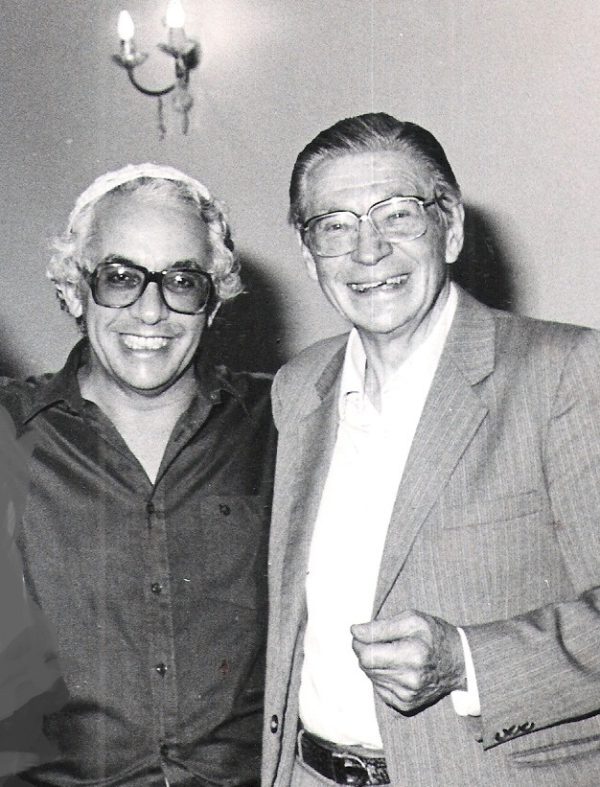

Nelson Mandela with former employer Lazar Sidelsky (right) and former fellow articled clerk and friend Nat Bregman, circa. 1994

[i] Most notably the exhibition ‘Looking Back: Jews in the Struggle for Democracy and Human Rights in South Africa’, mounted by the Isaac and Jessie Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research, 1997.

[ii] Cited in Adler, F H, ‘South African Jews and Apartheid’, in Patterns of Prejudice, © Institute for Jewish Policy Research, vol. 34, no. 34, 2000.

[iii] Most notably at its 33rd biennial conference, 31 May-2 June 1985.

[iv] Suttner, Immanuel (ed.), Cutting Through the Mountain: Interviews with South African Jewish Activists, Viking, 1997, p44

[v] Shimoni, Gideon, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa (Johannesburg: David Philip, 2003), 74, makes a distinction between “liberals,” whom he defines as those who confronted the apartheid system only within the parameters deemed legal by the regnant white polity and ‘radicals,” most but not all of whom were Communists, who went beyond those parameters.

[vi] Saks, David, ‘Jews and Communism in South Africa’ in Hoffman, M B and Srebrnik, H F (eds.), A Vanished Ideology, A: Essays on the Jewish Communist Movement in the English-speaking world in the 20th Century, University of Albany Press, 2016.

[vii] I thank Mr Pogrund for making these unpublished notes available to me.

[viii] For more on the baleful influence of Neo-Nazi and radical antisemitic ideologies during this period, see in particular Shain, Milton, A Perfect Storm: Antisemitism in South Africa, 1930-1948, Jonathan Ball, 2015

[ix] Veteran Struggle activist Albie Sachs provided a characteristically more nuanced comment on the question: ‘Philosophically, I have no doubts: Jews have no greater entitlement to be callous or any larger responsibility to be sensitive than anyone else. Yet in my heart I am especially shocked when Jews speak and behave in a racist manner’, Jewish Quarterly, Spring, 1993.

[x] Shimoni, p113

[xi] SA Jewish Board of Deputies - SA Rochlin Archives: Biog. 303 Goldreich A.

[xii] Ungar was briefly the rabbi of the Port Elizabeth Reform community during the 1950s. As a result of his outspoken broadsides against apartheid policy, he became the only Jewish cleric since Joseph Herman Hertz to be effectively expelled from the country for his political activities when the authorities refused to renew his work visa.

[xiii] Rabbi Ben Isaacson – Personal communication, 2015.

[xiv] Minutes of the 33rd national conference of the SAJBD, 30 May-2 June 1985

[xv] Smith, M, ‘Apartheid and South African Jewry’ in Jewish Affairs, Vol. 58, No. 4, Chanukah 2003

READERS' COMMENTS

As one of the co-authors of Worlds Apart: The Re-migration of South African Jews, I write to suggest that some of what you have written does not accord with our research.

"The majority of its members consisted of first and second generation immigrants from Eastern Europe, whose Jewish communities had been all but annihilated. Of the remainder, many were refugees from Germany, or originally came from the island of Rhodes, whose Jewish population was likewise almost wiped out. It would have been difficult to find a single Jewish family in the country who had not lost close relatives." (My emphases.)

We gave this topic significant attention in our book. As it is now out-of-print, I am attaching the relevant chapter.

It seems as if you have muddled the generations. As my co-author, Professor Colin Tatz ז״ל, often said, "The Holocaust passed South Africa by." The post-war generations of Jews, who lived under apartheid, were mainly third and fourth generation, not first and second.

The ('Russian') Jews (mainly Litvaks) had started arriving in the wake of the diamond and gold discoveries, in the second half of the 19C. Jewish immigration slowed considerably after WW1, and was banned by the SA government in the 1930s.

Most families were like my mother's and father's.

My paternal zeide arrived in SA in 1897. His entry papers say "Russian" and "miner". He was following an aunt who had arrived in 1870 ('chain migration'). His first cousins, eight of them, also started arriving in 1897. Others went, around that time, to the USA. My maternal zeide married my bobbe in Middelburg in 1890.

For families like these, the Holocaust happened to distant relatives 50 or more years after they, themselves, had emigrated. Most known relatives had emigrated well before 1941, when the Germans invaded. (Extract from our book follows.) I have traced some of my such distant relatives to the USA.

In the 1897 census, the Lithuanian Jewish population numbered 755 000 persons.4 By the time of the 1923 census, Jews in Lithuania numbered somewhere between 153,743 (the American Jewish Year Book figure) and 250,000 (Dov Levin’s figure). Experts consider the 1923 census misleading because Vilnius was (politically) in Poland between the two World Wars. (In the 1925 census, there were 95,675 Jews in Latvia).5 This massive reduction in numbers was essentially because of migration to Western Europe, the United States, Argentina, Palestine, Canada and South Africa. By the time the Nazis arrived in June 1941, the Lithuanian Jewish population was approximately one-third of the 1897 figure, 220,000 according to both Levin6 and Efraim Zuroff,7 as a result of poverty, persecution, pogroms and the prospect of better life in other places. The ultimate demise of Lithuanian Jewry is a dramatic case study of genocide: from some 220,000 in 1941 to perhaps only 5,000 today. (My emphases.)

A minority of Jews living in SA in 1948 and throughout apartheid were like my wife's parents (first generation), who arrived in SA in the late 1920s, leaving behind parents, siblings, cousins and other close relatives who were all killed.

Colin would have appreciated what you wrote about his first cousin, Rabbi Bennie Isaacson, with whom Colin and I were at high school. I would never have imaged that member of our rowdy gang becoming a rabbi!

Dr Peter Arnold,

NSW, Australia

P.S. anyone interested in obtaining a digital copy of our book can contact me at parnold@ozemail.com.au

David Saks writes:

Thank-you for this considered response on this aspect of my article. What I perhaps should have written was “1st, 2nd or at most 3rd-generation….” Better still, I should have made clearer that when referring to first & second generation SA Jews, the time period I had in mind was in the years immediately following the Holocaust, and not later decades, when there would certainly have been many third and indeed growing numbers of fourth generation Jews in the country. In 1945, though, I think it is correct to say that most of the community would have been first or second generation, with a smaller number of 3rd generation members.

Put simply, the majority of Jews who lived under apartheid were indeed third and fourth generations (certainly after about 1960s), but in the immediate post-war period leading in to the early years of the post-1948 National Party administration, the majority probably still would have been 1st or second generation.